What's New

To Stand Up a Stone

The following blog post originated as an address given by Robert Shetterly at the Brunswick [Maine] Peace Fair on August 3, 2019.

I was talking with my friend Roger Kirby recently about his work. He’s a painter. He’s English and summers in Brooksville [Maine] near me. He told me he’s become fascinated with the ancient standing stones located in over 1,000 sites around the U.K. and Brittany. These mysterious stones, often arranged in circles, date from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages four to five thousand years ago. Roger is attempting to make paintings – not depicting the stones so much as how he feels in the presence of them.

In the midst of our conversation, after I had asked him about the significance of the stones, Roger said, “The original human creative act is to stand up a stone.” I thought: What an interesting thing to say and how might that true?

The stone at rest has been sleeping for centuries. Dreaming since the last ice age. Its placidity may call attention to its beauty and its integration into nature. In some sense, then, might it be presumptuous to stand up a stone? Intrusive? But stand it up and its role changes. It’s invigorated, individuated, inspirited. Has potency. It has ritualized its space. Sanctified – perhaps like an altar without a church. It commands and shapes the space. It focuses attention. Calls the residents of the area to be in relation to it. It teaches a kind of adherence to its posture. It casts a shadow. And the shadow becomes the keeper of time, the arbiter of time.

Its standing role is not to dominate but remind one to be present, to be conscious, reminding one of one’s consciousness. Perhaps it is creative because it is the result of a newly conscious mind, the mind with a will to rearrange nature. Or, perhaps the act of standing the stone up created that new consciousness – the way any truly creative act does. A creative act always challenges one to think and feel, sometimes act, differently in response to it. The landscape with a standing stone becomes a conscious landscape, conscious of its own history in time. The standing stone is the ambassador of the mute world to the conscious world. The messenger, the emissary. It offers a spiritual partnership, a conversation between the land and the mind. It is not destructive or exploitative; rather, it’s a call to harmony. It anchors. Provides an address, signifies home. The standing stone sounds the awakened land’s first clear note of human creativity in relation to nature’s.

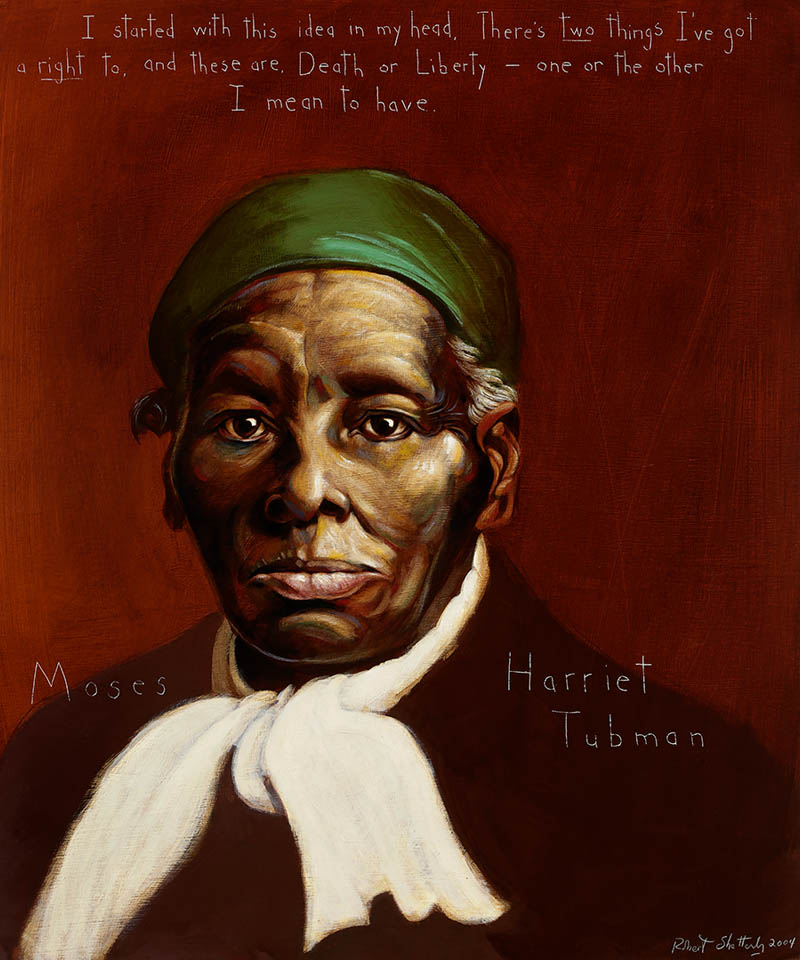

An act of moral courage is like a stone stood up. An act of moral courage rearranges a social space and redefines community. A person standing up resists the mythology and propaganda of violence, of separation, of racism, of dehumanization, of exploitation, of power and of the justified injustice of the status quo – the way a shadowless pasture of conformity and corporate docility becomes redefined by the standing stone of the iconoclast, the truth teller. The paddock of slavery redefined by Harriet Tubman. The field of status quo history reorganized by the standing stone of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History. The long metallic arc of male dominance re-bent by the militancy of Alice Paul. The massive bloom of invisible secrets made visible by the standing stone of Daniel Ellsberg.

Most of the Neolithic stones are in circles, like seasons and cycles, like congregations in conversation, like restorative justice circles, praying, chanting. They amplify the land’s heartbeat by sounding the human. The standing stone is the sentry for what is above and what is below. To stand a stone may be the first creative act; it may also be the first committed act. It commits to taking the materials of nature and crafting human identity, community and dignity. I say “dignity” because the stone seems a declaration of pride. Pride more than egotism. Not separate from but in relation to.

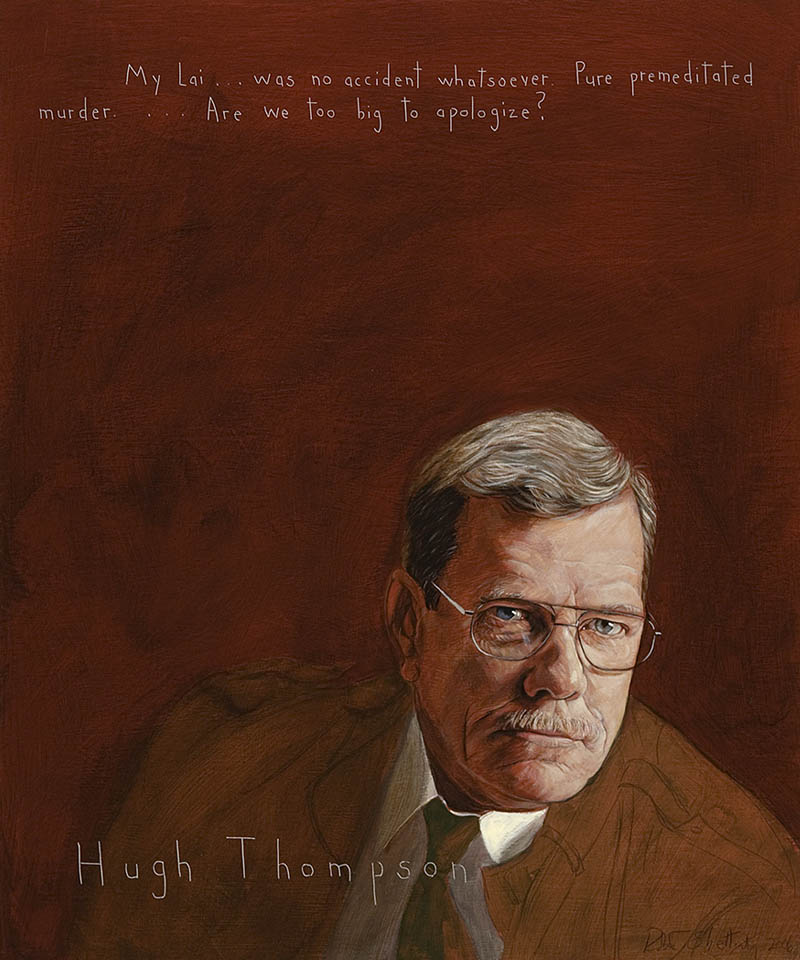

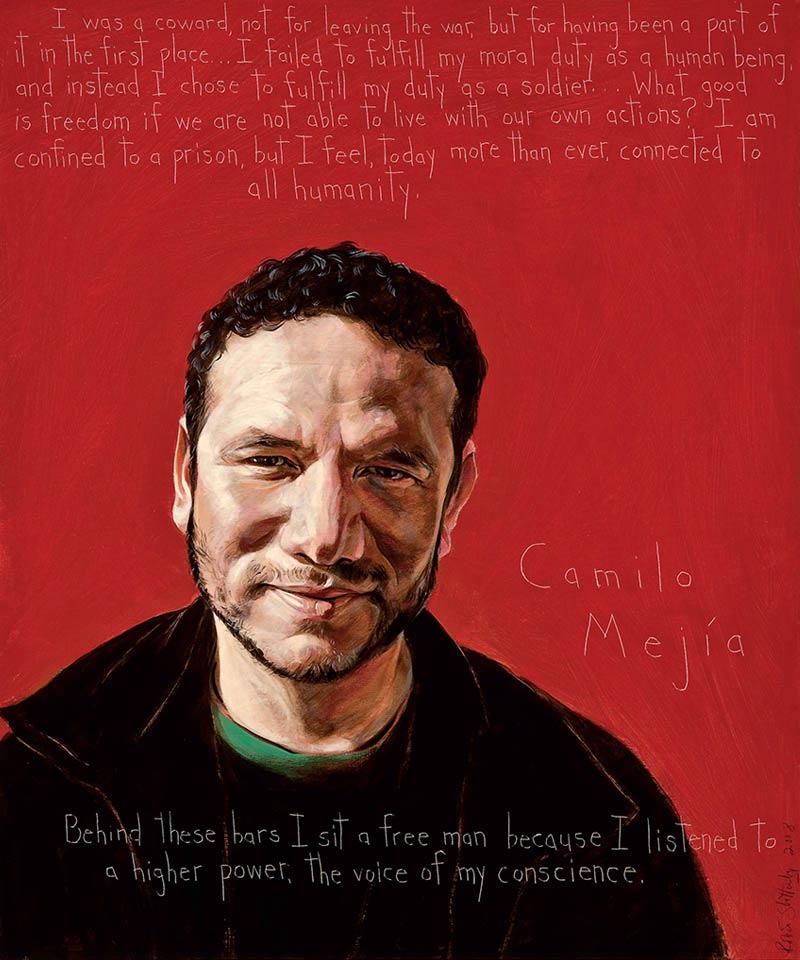

The original creative act of the common good is the standing-up person, the signal that justice has a heartbeat, the truth that compassion requires courage. The standing stone of moral courage evolves the consciousness of the community. It exposes the truth that power hates ceding control, scorns equality, will do practically anything to subvert real democracy. The standing stone envisions and makes possible the dignity of other stones. The crazed murderers at My Lai discover their shame in front of the standing stone of Hugh Thompson. A poor Palestinian home remains standing because Rachel Corrie’s standing, once enacted, cannot be knocked down with a bulldozer no matter how many times the driver runs over her. In jail Camilo Mejia says now he is finally free because he has followed his conscience and refused to continue participation in an illegal, immoral war. His stone stands in prison. He says he was a coward – not for refusing to fight, but a coward for having accepted taking part in the war in the first place, a coward for fighting. Right here in Brunswick, Bruce Gagnon stands up in the backyard of Bath Iron Works and General Dynamics demanding conversion from warship militarism to sanity and green infrastructure sustainability. Consciousness changes, a community grows. A standing stone is a creative act, a committed act.

William Sloane Coffin said, “”Socrates had it wrong; it is not the unexamined but finally the uncommitted life that is not worth living.” The standing of moral courage creates its place, its address in history, because it creates value, creates worth. It makes a claim to nobility that would otherwise be preposterous.

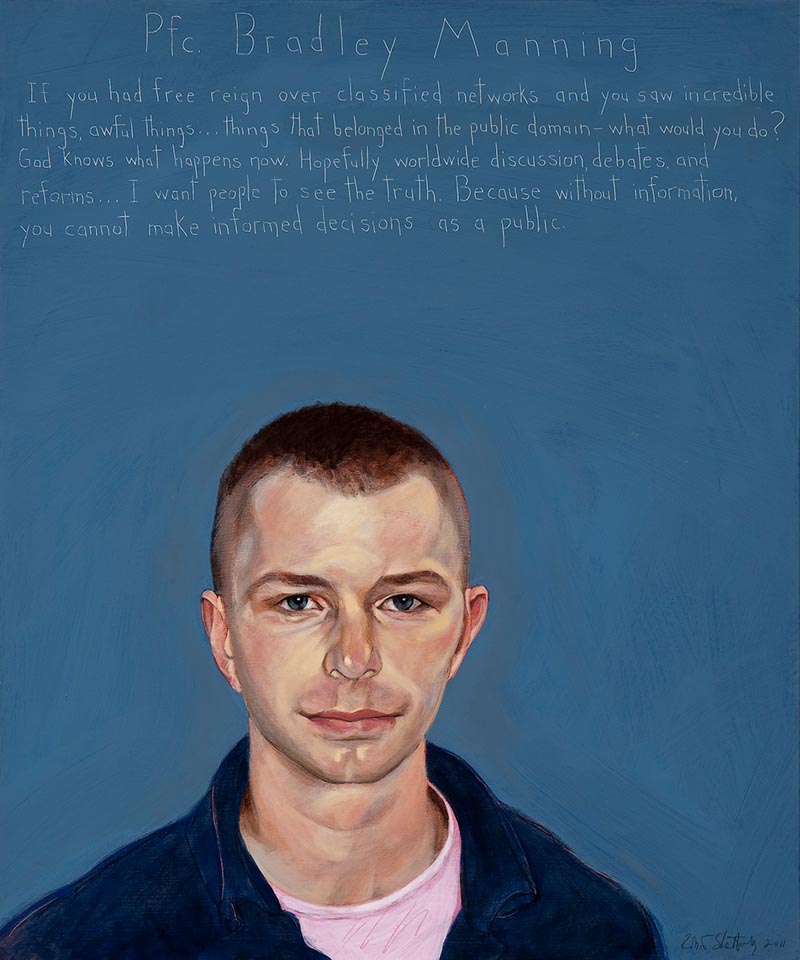

Think how power has tried to deface the standing of Chelsea Manning. The more mud they sling, the more hateful graffiti scrawled on her, the more law wielded like shears to cut her stature down, the taller and more adamant she stands – revealing now not only crimes against humanity but the oppressive crimes committed to make her silent and invisible.

There is a kind of meaning, a claim to stature, in our lives that can only be purchased with courage.

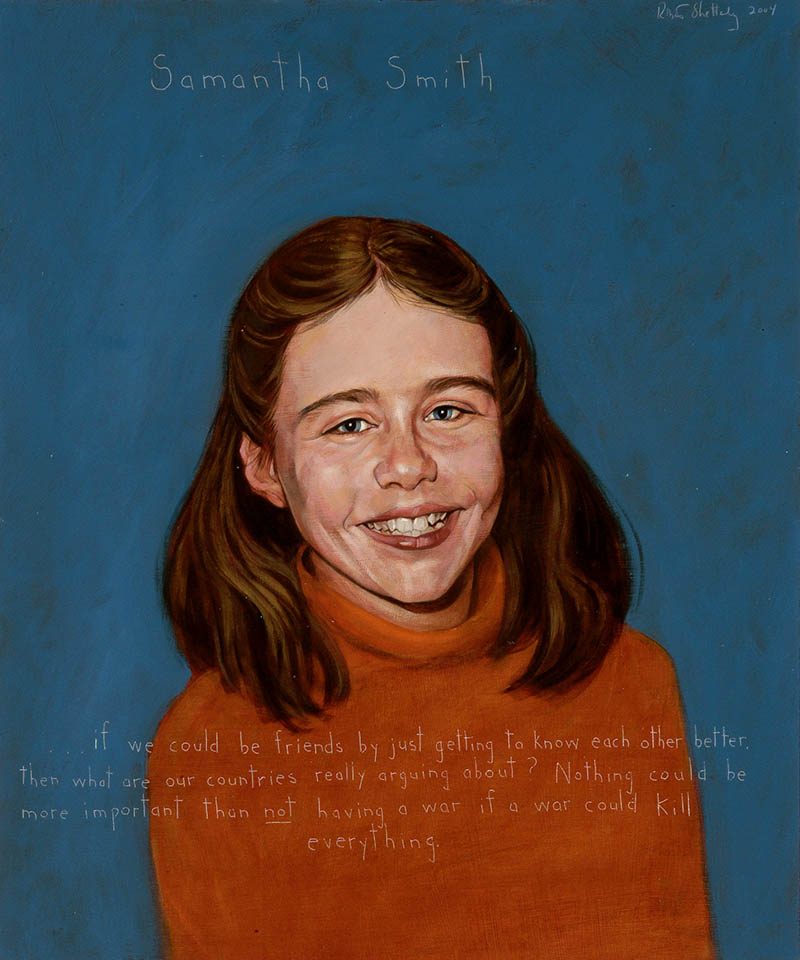

Think of Samantha Smith, a ten year old frightened of nuclear holocaust, who launches a letter like a kite, and she clings to the tail of that kite until, floating above us, she is teaching adults how to recognize the absurd manipulations of the Cold War. A standing stone.

In 1969 Fred Branfman, a young American teacher in Laos, recorded the terrifying experiences of poor rice farmers fleeing from round-the-clock U.S. carpet bombing on the Plain of Jars. He returned to the U.S. and testified about this Secret War being mercilessly and illegally waged by the U.S. against these voiceless civilians. A standing stone.

Standing stones are cairns. They mark the track of justice and morality in an otherwise baffling and trackless landscape. They are the dots we need to connect. They are the map of the narrative we must tell. Without them our consciousness cannot evolve beyond the propaganda of power. Without them justice has no heartbeat. The original human creative act is to be a standing stone.