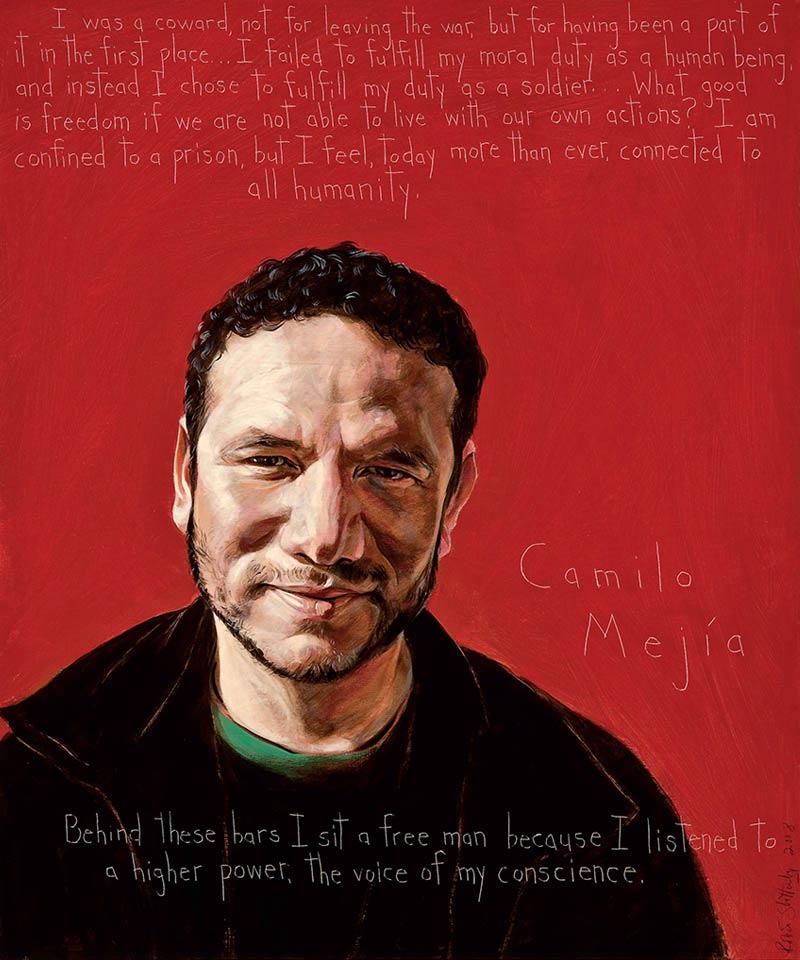

Camilo Mejia

Soldier, War Resister, Peace Activist : b. 1975

“I was a coward, not for leaving the war, but for having been a part of it in the first place. I failed to fulfill my moral duty as a human being, and instead I chose to fulfill my duty as a soldier. What good is freedom if we are not able to live with our own actions? I am confined to a prison, but I feel, today more than ever, connected to all humanity. Behind these bars I sit a free man because I listened to a higher power, the voice of my conscience.”

Biography

Camilo Mejia was born in Managua, Nicaragua in 1975. His family moved to Costa Rica and then to the United States where he finished high school in New York City. Mejia never applied for or received US Citizenship. Nevertheless, he went to college at the University of Miami on a military funded scholarship where he intended to major in psychology and Spanish. But, in the spring of 2003, before he had finished college, the military sent Mejia to Iraq where he spent five months in active combat and then he was posted to Jordan where he spent two more months.

In late 2003, he came home to US on furlough and realized he could not go back: “Going home gave me the opportunity to put my thoughts in order and to listen to what my conscience had to say…. I thought of the suffering of a people whose country was in ruins and who were further humiliated by the raids, patrols and curfews of an occupying army. And I realized that none of the reasons we were told about why we were in Iraq turned out to be true…. There were no weapons of mass destruction. There was no link between Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda. We weren’t helping the Iraqi people and the Iraqi people didn’t want us there. We weren’t preventing terrorism or making Americans safer… I realized that I was part of a war that I believed was immoral and criminal, a war of aggression, a war of imperial domination. I realized that acting upon my principles became incompatible with my role in the military, and I decided that I could not return to Iraq.” He filed for conscientious objector status and told the military he refused to return to the battlefield.

In May of 2004, Mejia was convicted of desertion by the US Military–a charge which can be punishable by death–and sentenced to a year in jail. He served his time at Fort Sill military prison in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. During his incarceration, Amnesty International recognized him as a prisoner of conscience and the activist organization Refuse and Resist gave him their Courageous Resister Award.

Since his release in February of 2005, Mejia has devoted his time to speaking out against the war in Iraq and encouraging others to understand that being a part of an immoral war was more cowardly than breaking the law: “I was a coward not for leaving the war but for being a part of it in the first place,” he said. He has written a book called The Road from Ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Seargeant Camilo Mejia (The New Press, 2007) that details his experience. In August of 2007, Camilo Mejia became the chair of the board for the non-profit organization Iraq Veterans Against the War.

Mejia lives in Miami where he spends a lot of time with his young daughter. He has completed his final semester at the University of Miami and received his Bachelor’s degrees in Spanish and Psychology. If given the opportunity he would like to become a US Citizen. In the meantime, he will continue to speak out against a war and a military policy that takes immigrants and poor people and obligates them to fight, even against their consciences.

Mejia says that being a hero does not take anything special, just the belief that one person can make a difference: “Many have called me a coward, others have called me a hero. I believe I can be found somewhere in the middle. To those who have called me a hero, I say that I don’t believe in heroes, but I believe that ordinary people can do extraordinary things”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.