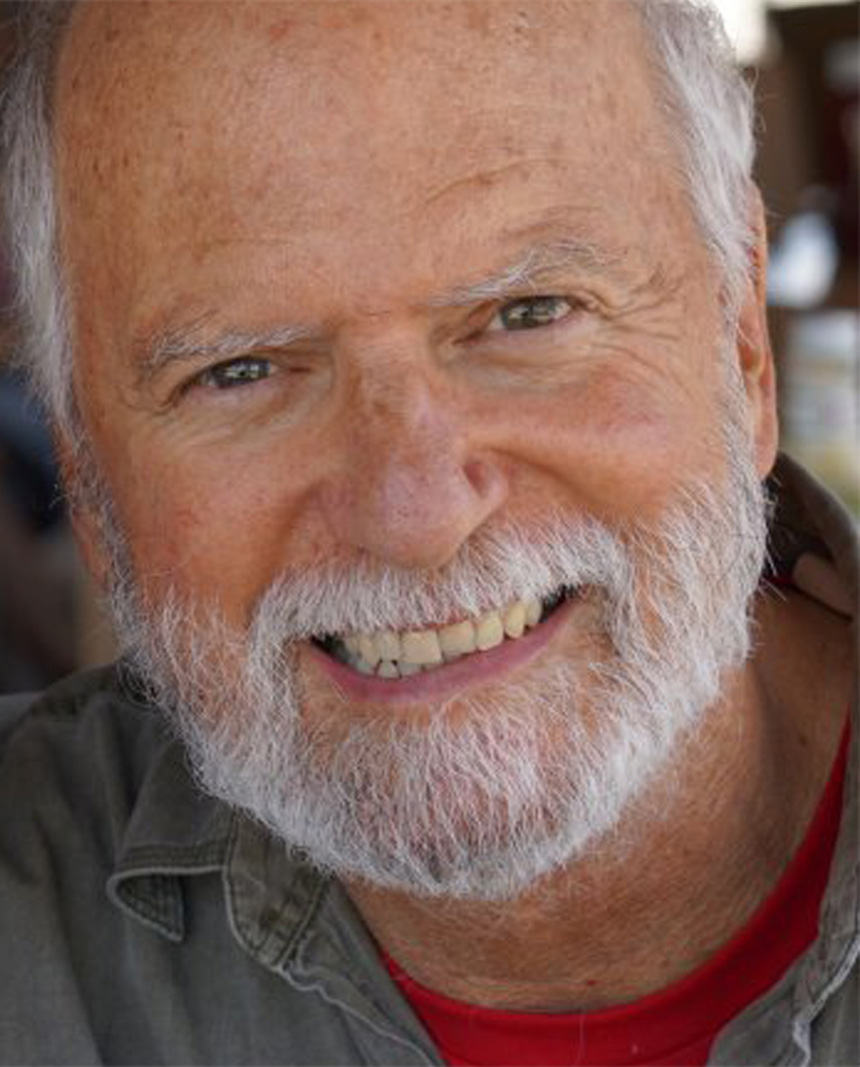

Robert Shetterly

“The burden of continual injustices and angers is more than one person can bear–or should. And consequently I’m constantly replete with admiration and love for the people I’ve painted who so fiercely bear those burdens.”

Biography

Robert Shetterly was born in 1946 in Cincinnati, Ohio. He graduated in 1969 from Harvard College with a degree in English Literature. At Harvard he took some courses in drawing which changed the direction of his creative life — from the written word to the image. Also, during this time, he was active in Civil Rights and in the Anti-Vietnam War movement

After college and moving to Maine in 1970, he taught himself drawing, printmaking, and painting. While trying to become proficient in printmaking and painting, he illustrated widely. For twelve years he did the editorial page drawings for The Maine Times newspaper and illustrated National Audubon’s children’s newspaper Audubon Adventures and approximately 30 books.

Robert’s paintings and prints are in collections all over the U.S. and Europe. A collection of his drawings and etchings, Speaking Fire at Stones, was published in 1993. He is well known for his series of 70 painted etchings based on William Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell,” and for another series of 50 painted etchings reflecting on the metaphor of the Annunciation. His painting has tended toward the narrative and the surreal; however, for more than 20 years he has been painting the series of portraits Americans Who Tell the Truth. These portraits have been traveling around the country since 2003. Venues have included everything from university museums and grade school libraries to sandwich shops, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City, and the Superior Court in San Francisco. To date, the exhibits have visited 35 states. In 2005, Dutton published a book of the portraits by the same name. In 2006, the book won the top award of the International Reading Association for Intermediate non-fiction. New Village Press in New York City is currently publishing a series of themed books on the portraits. Each volume contains 50 portraits. The first two are Portraits of Racial Justice (2021) and Portraits of Earth Justice (2022).

The portraits have given Shetterly an opportunity to speak with children and adults all over this country about the necessity of dissent in a democracy, the obligations of citizenship, sustainability, US history, and how democracy cannot function if politicians don’t tell the truth, if the media don’t report it, and if the people don’t demand it.

Shetterly has engaged in a wide variety of activist and humanitarian work with many of the people whose portraits he has painted. In the spring of 2007, he traveled to Rwanda with Lily Yeh and Terry Tempest Williams to work in a village of survivors of the 1994 genocide there. And then to Palestine twice with Lily Yeh for art projects in refugee camps. Much of his current work focuses on the intersections of climate change, systemic racism and militarism.

For 25 years he was the President of the Union of Maine Visual Artists (UMVA) and a producer of the UMVA’s Maine Masters Project, an on-going series of video documentaries about Maine artists.

Richard Kane’s film Truth Tellers about the Americans Who Tell the Truth project premiered in the fall of 2021 and has been showing across the country. In July 2022 it played at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Robert Shetterly lives with his partner Gail Page, a painter and children’s book writer and illustrator, in Brooksville, Maine

Awards & Commendations

- In 2005, the Maine People’s Alliance awarded Robert its Rising Tide award.

- Also in 2005, he was named an Honorary Member of the Maine Chapter of Veterans for Peace.

- In May 2007, he received a Distinguished Achievement Award from the University of Southern Maine and gave the Commencement Address at the University of New England which awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters.

- In 2009, he was named a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow, enabling him to do week-long residences in colleges around the country.

- The University of Maine at Farmington awarded him an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 2011.

Artist Statements

In January 2022, AWTT turned twenty years old.

I’m seventy-five years old and still as hungry for experience, knowledge, understanding, and courageous role models as I was at fifty-five. People my age are usually clearing the decks–holding garage sales, packing for Goodwill, setting boxes of old books and ugly crockery at the curb, writing codicils to the will. But as time grows shorter for me, I want to drink deeply of the world’s best distilled time–keep adding exemplary citizens to this company of truth tellers, strengthen this pictorial indictment of corruption and violence, reinforce this bulwark against racism and hypocrisy, polish this mirror of love and justice, deepen this catalog of inspiration. Americans Who Tell the Truth has tried to be a lantern that throws its light forward and back–knowing the truth of the past’s struggles for justice is essential to seeing clearly the obstacles and possibilities in the future.

That last sentence sounds suspiciously like the old saw warning that either we learn our history or we’ll be doomed to repeat it. What twenty years of this project has taught is something else. Powerful people often study the history of exploitation, the tricks and methods of corruption, precisely so that they can repeat them as long as their victims will submit. Early on I learned this from Frederick Douglass: “Find out what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong that will be imposed on them.” Douglass understood the psychology and mechanisms of power as well as anyone you could ever meet while traveling through our history. Some people who have learned their history well will impose injustice again and again. Others, who have also learned that history, will, like the people in the portraits, resist injustice again and again. Our job is to learn the courage of history so we can resist and change it.

These days the flame of my anger at injustice still burns brightly; yet, navigating the world’s injustices is like running a gauntlet of moral insults. The burden of continual injustices and angers is more than one person can bear–or should. And consequently I’m constantly replete with admiration and love for the people I’ve painted who so fiercely bear those burdens.

However, I’m also less confident that this country will solve its environmental, social, and racial justice issues, and more amazed at the depth of ignorance, racism, and belligerent nastiness in some quarters. One is tempted to contend that this ignorance is willful. And it may be in part, but I prefer to think it’s the result of cynical leadership stoking the flames of prejudice and racism. I prefer that explanation because it offers a way out–more honest and deeply informed teaching and leadership (which just happens to be the mission of AWTT). Better teaching does not offer a quick, magic exit from the maze of our own prejudice, partisanship, violence, and environmental devastation; it offers a string to follow out of the darkness.

AWTT began as a personal statement against the lies of the George W. Bush administration in 2001-2003, lies used to justify making preemptive war on the country of Iraq (a war as morally reprehensible as Russia’s attack on Ukraine today). That attack was a purposeful war crime, a crime against humanity presented to the American people as a war necessary for our security. With AWTT, I attempted to speak truth to power, to find a defiant means of practicing citizenship in a country committing imperialist crimes. By aligning myself, through the portraits, with the legacy of resistance to injustice, I could separate myself from status quo America while, at the same time, feel less alienated from its spoken values–distanced from this country’s acts, closer to its words. I was using art to create a Here I Stand ultimatum by naming with whom I stand.

Just as the past twenty years have been punctuated more and more frequently with extreme weather events, so too our history has been assaulted by extremities and crises–political, constitutional, economic, moral, and physical. The air is so dense with historical dust, hardly anyone can see back twenty years to the criminal acts instigating the Iraq War. The visibility is so poor, it seems all we can do is struggle to see our own feet, much less peer weakly ahead. The recent past is a disappearing shadow, the future full of frightening uncertainty.

And yet, if we don’t remember the truth of this past, it can deteriorate into irrelevance and be used as a model for the next president of how to get away with an illegal war.

Who really cares that George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, and Paul Wolfowitz, et al., are war criminals? They take their honored place in a long roster of imperial criminals who were never held accountable. In a country that thrives on imperialism, it’s no surprise that the imperialists themselves, no matter how egregious their crimes, are rewarded. They dispense a bit of their reward to endow libraries, university buildings and public spaces so that they are remembered as exemplary and generous spirits. Perhaps a Wikipedia footnote may suggest some involvement with questionable policy. Ho-hum.

Twenty years ago I felt that creating AWTT was like making a whistle stop tour across America, crisscrossing the heartland from coast to coast, traveling forward and backward in time, picking up courageous citizens as we chugged along, each posing for a portrait in the dining car, then urged out onto the platform of the caboose to shout rousing truths to people lining the tracks as we slowed through towns and cities, past schools and colleges, libraries and union halls. Early on I insisted that most speeches be about the duplicity of war and war making, but then the focus shifted to racial injustice, indigenous genocide, sexism, and corporate exploitation. Environmental and climate change activists elbowed in, insisting on the urgency of their warnings. Impatience overtook the entire trainload; all the portraits demanded to speak at once. Some of those who heard that righteous, raucous AWTT chorus called it cacophony; others recognized it as intersectionality. The portraits have become a multitude, all infused with love and courage and each would proclaim–along with Whitman (the first portrait):

And whoever walks a furlong without sympathy walks

to his own funeral drest in his shroud…

–from Song of Myself

There’s a bitter controversy these days about what’s called Critical Race Theory (CRT), a term that, as far as I know, had not even been invented twenty years ago. Its name suggests something academic and elitist, abstract and confusing, a bludgeon wielded by a bunch of angry, self-righteous, liberal PhDs to force innocent white 5th grade boys and girls in Texas and Florida to relinquish their benign, patriotic world view, make them ashamed of their lineage, turn them against their parents and country, and ultimately hate themselves. By those lights, Critical Race Theory is a mean-spirited attempt of one group to oppress another and force them to interpret the world their way.

That’s absurd. CRT’s intent is to say to Americans that if we want to talk about our history and how that history has shaped our institutions, our economy and its lopsided distribution of wealth, our unequal education system, the psychology of our various peoples, we need to tell the truth about what that history is. It’s like we’re in 9th grade biology class and we are given frogs to dissect. Some politicians decide students can learn everything they need to learn about frogs by dissecting tomatoes. Tomatoes are prettier . . . They don’t make us think about our insides. Real history is about our real insides. If we don’t see what’s really there, we don’t inhabit our own history, we don’t understand how the organism works. Not understanding is the epitome of exceptionalism: such a stance insists there’s no way exceptional people, like us, could possibly have a brutal, racist, misogynist history. So, therefore, we don’t! We’ve had the experience but have excused ourselves from the burden and truth of its meaning.

When we have, occasionally, set out on a course of reckoning, like Reconstruction after the Civil War–attempting to align our values with our behavior, changing the present to correct for the injustices of the past–powerful white people, north and south, chose instead to embrace Jim Crow and the malignancy of forgetting, so the profit and control of those injustices could fester and multiply. When we allow ourselves to forget the humanity of the victims of our hypocrisy, the flaws of the founding fathers loom bigger than ever.

Honest identity has to be about remembering, about reconciling in the presence of the truth rather than in the shadows outside it. It would seem that truly exceptional people would choose to take a long gaze in the mirror. At the close of the George W. Bush administration, one of Barack Obama’s first acts was to declare that he would not seek any legal accountability for the crimes committed by Bush and his cronies, among them lying to the American people, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and torture. Obama was choosing forgetting over remembering, the comfortable stupor of amnesia over the tough rule of law. He chose to paint the mirror black. When the powerful choose to forget, they dismiss the value of the lives of all the people harmed by the injustice. In order for us to maintain our innocence and political equilibrium, we erase what we did. This is not the same as saying, “The past is the past, let’s move on.” It’s saying, “The past never happened. All those people who were victims of our behavior are collateral damage to our entitlement, martyrs for our righteous cause. The greatness of America absolves us from counting and naming them.”

Those injustices didn’t just happen once and disappear. They were woven into systems of dominance and profit, a social and economic legacy that continues today. That’s the true history and there’s no point calling ourselves Americans if we don’t include the experience of all Americans and those harmed by Americans, the experience lived and the experience suffered.

Imagine that you’ve decided to undertake a vision quest into your national identity, a long trek through unfamiliar long-denied territory. On the horizon you see steep mountains, jagged, with high treacherous peaks. Smartly, you decide to go into your local, official history guide shop and purchase a map. You kneel down by the trail and spread out the map. You’re surprised to see no mountain range mapped in. Should you be relieved? If the mountains are not on the map, maybe they don’t exist? No, you’re smarter than that. You return to the guide shop and say, “This must be the wrong map. There’s no mountain range.” The politician behind the counter sighs and says, “Oh, we left out the mountains because the way through is tricky and challenging; it might give you the wrong idea about what a beneficent country this is. Better to walk in circles on this side of the mountains.”

But we know if you want to call yourself an American, you need to traverse those mountains. It’s hard. It’s uncomfortable. Infuriating. It’s dark and sad. It’s humbling. Makes you feel guilty for events you feel you can do nothing about. It’s also exhilarating. Inspiring and wondrous. The mountains are full of caves. You’ll find Jefferson Davis living in one, John Wilkes Booth in another. You’ll stumble into Frederick Douglass and Jane Addams. Then, the Georges–General Custer and George Wallace. But also John Brown. You’ll find Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King, Jr., Ronald Reagan and Daniel Ellsberg, Caesar Chavez and Grace Lee Boggs, Ella Baker, and Barbara Johns.

An issue that has come up obliquely but never directly addressed in the twenty years of AWTT is the question of the relationship of heroes to democracy. I’ve been reading the book Looking For the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness, by Elizabeth Samet, in which she says, “…heroes should be understood as inherently undemocratic.” What she means is that it’s an easy (lazy) temptation for people to look to heroes to solve their problems, wanting heroes to relieve them of the responsibilities of being good citizens and organizing together for change. The worship of heroes in a horizontal society gradually turns the axis to the vertical, the hierarchical; hero worship may shrug into the cult of personality, then autocracy. Democracies can subvert themselves in many other ways, too–such as allowing for extreme income disparity, allowing special interest money to control political policy, promoting a form of freedom that allows the powerful individual to have no responsibility to the community, or using secrecy to hide government actions, teaching flattering myth rather than complicated reality. That’s why we have maintained at AWTT that the portraits are models of courageous citizenship. We do not place them on pedestals. They are selected as real, complex human beings, whose acts for the common good can be emulated by all of us, any of us–need to be emulated by all of us! The saving grace of a healthy democracy is not a handful of heroes but a culture of engaged citizenship inspired by the courage of truth tellers. Courage invigorates democracy; hero worship enervates it.

While I was thinking about the danger of hero worship, it occurred to me that another form of it plays out on a national scale when the myth of the country is maintained to be flawlessly heroic. This is the idea of exceptionalism, i.e., we are the indispensable and always good country whose simultaneous embrace of military power and democratic values entitles us–ordains us!–to dictate the world’s distribution of resources, the naming of values, and the direction of history. We are the hero country. It should be obvious how such a stance corrupts democratic discussion at home and demands the antithesis of democracy among nations. Professing exceptionality is a euphemism for self-righteous superiority. It’s a form of national sanitizing where all the country’s deeds–noble as well as abominable–are sanitized into one flawless identity. The country’s citizens are encouraged to believe and act out this mythic perfection.

The question at the heart of AWTT is simple: Do we want to construct our identities from complex truths or from easy and flattering untruths? An identity shaped by complex truths is as humbling as it is freeing. Then we can see the world as it is and shoulder the necessary responsibilities. Voltaire is famous for saying, “Anyone who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.” I am exhausted by living in a country that justifies the atrocities it commits as the epitome of patriotism. Let’s ennoble ourselves by insisting on believing in the justice and hard work of our own ideals. Let’s commit citizenship for the common good.

When I was a teenager, I read for the first time about Jainism, a religion practiced by millions of people in India. Jains believe in extreme non-violence. What particularly caught my attention was their habit, which seemed laughable and obsessive, of sweeping the ground before them as they walked. To injure a single tiny ant or little beetle was to injure the soul of a creature equal to themselves. We Americans knew how silly that was! We casually step on ants and beetles with no consequence–or so we thought. Today, as we reel from the cascade of species extinctions, Jainism appears the far more sensible relationship to Nature. Moreover, we have been in the habit of sweeping, too–not in front of us to avoid harming other creatures, but behind us so we don’t remember. For twenty years it has been the mission of Americans Who Tell the Truth to teach responsibility for the injustices we create and provide role models for how to remedy them for a just society.

— Robert Shetterly

The Americans Who Tell the Truth project began with art. Part of the reason for that is obvious: I am an artist. And I choose art because it enables me to communicate most profoundly and honestly. When I say communicate, however, I don’t mean that my first concern is communicating with other people. Art allows me to communicate with myself. I paint an image; the image then speaks back to me, informs me of ideas and concerns beyond what I knew I had. The painting becomes a tangible fact in the world whose reality tells its own story. If it tells that story to me, I’m confident it will speak to others.

In the run-up to the Iraq War when I was convinced that many political, military and media figures were lying about the reasons for war, I decided to surround myself with Americans whom I trusted and respected, Americans who had struggled to uphold our fundamental ideals. Truth tellers. I could have written down their names in a notebook. I could have thumb-tacked photos of them to a wall. But neither of those acts would have engaged me in a creative process of respect and recognition the way painting a portrait does. Neither would have required prolonged effort, the kind of effort which committed me to do something about this criminal war. To paint a good portrait one must concentrate hard for many days to fully honor the subject of the portrait, to discover a likeness which not only looks like the person, but speaks like the person, radiates something essential about that person, from that unique person. Art requires an investment of critical and loving energy. If that energy is well used, the portrait will speak with critical and loving energy. Other people will feel it. This process is one of the deep mysteries of art making. Done well, a portrait evokes the presence of a person as no other medium can.

I did not want to feel totally alienated from my own country as the patriotic fervor grew for war. Among my gradually increasing collection of portraits, I found a community, a seemingly living community, where I felt consoled and empowered. I felt at home. Art can do that – bring you home.

Good art takes time. No matter how urgent the issues may be, the most lasting communication will be the most artful, art that strives for beauty and meaning and is willing to take the time to discover them. It was my determination that slowly building a community, portrait by portrait, of Americans who have fought for racial, economic, social and environmental justice would be the most persuasive and educationally useful thing I could do. Their power may be their invitation to a moment of contemplation, the permission they give viewers to stop and think, to agree or disagree, at the same time requiring that they acknowledge the humanity of the person represented before them. If the art can embody the truth of the person, the viewer may be willing to consider the truth of the subject’s words.

The contemplation, the permission, the humanity are all enhanced by the attempt to make real art. Having high standards for our art making shows that we respect the subjects, the viewers and ourselves.

We live in a time of historical and environmental urgency. We are besieged by a cacophony of propaganda, spin, and special interest voices. Most of those voices are purposeful, cheap distractions from the important issues and from the activist work we should be doing. The art of the portraits tries to call us back to essential issues and values, at the same time providing us with models of vision, courage, compassion and citizenship. This art does not insist that you agree with everything it says; it wants you, though, to look it in the eye, to know that what you see is an honest encounter with a real person with real courage working to close the gap between what we say about the common good and what we do. The portraits aspire to be a community of trust. You may disagree with some, but you can trust their intentions. And, in a sense, you could say that all of them are really one portrait, a historical portrait of a country struggling to live up to itself, to discover itself, to become its own dream. A portrait of the dignity of that ambition. Good art carries that burden.

Here are my answers to some questions I’ve been asked about the AWTT project:

What can ART do that other media can’t to combat the problems you articulate?

Art can transform the way a message is articulated and received. The medium of art is aesthetic, visual, and visceral. Non-verbal. It doesn’t attack the viewer but invites inquiry and participation. It gives the viewer space to think, feel, react and respond…or not. The viewer becomes the active participant. The portraits in particular try to present a person who emanates integrity, along with a statement about justice and compassion. They try to present an image of trustworthiness. They hope to elicit a response of integrity and trust and consideration of the issue in return.

What is the relationship between art and freedom of speech? How does your project interact with capitalism? With community? With education? With an individual viewer?

One of the expectations and obligations of artists is to use their craft and insight to tell truths many other people would be afraid to, due to peer pressure or job security. Artists who misuse their freedom of speech by lying or propagandizing are soon exposed as untrustworthy artists. Honest speech for an artist is a sacred trust.

Capitalism is nearly a national religion in the U.S. The creed of capitalism to expand markets and increase profits often becomes the justification for enormous damage to environment, law, the poor, peace, community, equality, democracy and morality. Capitalism values profit more than people and often dehumanizes people to enhance profit. Almost every portrait in the series has taken a position of moral courage on an issue stemming at least in part from the depredations of capitalism.

The portraits are meant to honor people often ignored or demeaned in the media and in our official history. A respectful portrait can help to reclaim the subject’s standing and role as a person worth listening to and emulating. This is the educational value.

What’s the difference between seeing one of your portraits and many of your portraits together at once? How does each of these experiences differ in terms of their impact? How can this group of paintings counter the obfuscations that you discuss?

When one views a large collection of the portraits, one is faced with the continuity of moral courage across time and issue, as well as the continuity of injustice. I think a single portrait can present a powerful story, but a collection presents a fabric of story. A viewer may want to use a single person as a role model but be part of the fabric. One may lead to the other.

If one studies the portraits, the issues, and their histories, one is led inevitably to see the obfuscations in the status quo narrative of America.

What would you like AWTTs impact to be? How does what you’ve done make you feel empowered and engaged? Is this exciting? Does it feel meaningful?

What I would like the impact of AWTT to be and what I can realistically expect it may be are two very different things. I would like people to reorient their sense of what’s good about this country by spending time with the portraits. That is, we are encouraged to believe that America’s

power and wealth derive from power and wealth. The lives of the portraits teach us that the power and wealth of the country are inherent in the insistence of courageous citizens that our country live up to its own ideals. In other words, our real power and our real wealth are found in how fiercely we embrace our ideals, not in our billionaires and Gross National Product. Every country has its powerful billionaires; few have our ideals.

Painting all these portraits over many years has required me to be engaged, to be a spokesperson for the lives and issues of the subjects. It’s been terrifically exciting to learn all this history, come close to the courage, participate as well as I can in some important truths.

Nothing could be more meaningful for me.

What are the limits of your project? Do these make you feel frustrated? Why do you resist talking about your paintings as paintings instead of as people?

As the portraits have multiplied, so have the expectations. It’s initial goal was art therapy for myself – to help me get through a difficult time in the history of this country and the world by aligning myself with truth tellers and activists. It’s taken on the responsibility of education for others. So, there are no actual limits except those of energy and awareness. I’m frustrated at times because I can’t – and the project can’t – do enough to cause needed change.

I like to talk about the paintings as paintings, and how I paint. But if I talk about them as people, it’s because I have tried to paint the spirit of each person. The portraits seem like people to me.

You have created a vast material body of work and expended a great deal of energy on these paintings. I think we should try to address these issues you raise through that body of work.

Yes.

What are the connections you’ve made between issues that never would have occurred to you if you hadn’t painted certain portraits?

It’s not an exaggeration to say that all the work on the portraits has been about painting, yes, but more so on education – mine. Perhaps the central understanding, that I had not fully appreciated before, was how the betrayal of the ideals of this country has been the conscious goal of wealth and power since the first white contact. Native genocide, slavery, exploitation of workers and environment, racism, the deification of the wealthy, corruption of law and politics to reinforce wealth and power, the propaganda to make the apotheosis of this power appear good and just. On the other side is the courage and nobility of the people who have struggled to insist the country be just, fair, and compassionate, in line with its stated ideals. Until I had painted many portraits I had not fully realized that the connection among all the issues (what we refer today to as intersectionality) is the tension between the willingness of power to do anything – ANYTHING! – to maintain its primacy and the power of tenacious courage to oppose it.

Another connection I had not fully valued – if that is the right word – and understood is my own privilege. Race privilege, wealth privilege. And how much of my life has been undergirded by that privilege. How much of power and wealth distribution, opportunity, in this country is shaped by that privilege. I feel the responsibility of that.

What issues didn’t you understand/were you ‘wrong’ about before you got into this project and learned more? What have you learned about yourself with this project over the last 18 years?

I was naive not to realize how systemic the problems were, the enormous reluctance of people and institutions to create more justice when jobs and security depend on the opposite.

I have learned about myself that I can mirror with the art the determination of many of the people I paint. I have learned how much I love learning, I love discovering what I have got wrong so I can learn more. I’ve learned that I prefer love and expressing love no matter how justified my rage may seem.

Perhaps the most important thing I have learned about myself is that because of the portraits, because I’ve taken the people and issues to heart, I am no longer intimidated by power and wealth, title and pedigree, prestige or uniform.

Do you consider yourself more an activist? More a painter? More a historian? Why?

If I consider myself more of a painter, I feel guilty for not being more of an activist. I have to believe that the art is the activism. And it is. I have come to love the history that surrounds the portraits, but I’m not a historian. I don’t know enough to call myself that. But I am a storyteller about history and how the lives of my subjects have affected history.

How have you grown as a painter? What do you think you can do/see as a painter now that you couldn’t before?

Hopefully, after nearly 250 portraits, my skills have improved. Counterintuitively, as I have improved as a portraitist, I think I’ve become more humble as an artist. I’m one guy trying to do one thing well. I don’t know if it really matters at all, but I can’t think of what I could do that would make me feel any more sure, any more engaged. Living in that doubt spurs me to try to make each portrait better than the last. If I were to give up painting the portraits to, say, work full time for 350.org, who would paint the portraits? I think of what Paul Robeson said, the quote I scratched into his portrait:

“The talents of an artist, small or great, are God given. They’ve nothing to do with him as a private person; they’re nothing to be proud of. They’re just a sacred trust… Having been given, I must give. Man shall not live by bread alone, and what the farmer does I must do. I must feed the people—with my songs.”

I don’t know if the portraits are ‘a sacred trust,’ but they are my sacred trust. I have a passion and a skill. Perhaps those two things are the only means I have to take full responsibility for my privilege.

— Robert Shetterly

Ten years. It’s been ten years since writing the first explanatory statement of why I was painting this series of portraits, Americans Who Tell the Truth. So much has changed, and so much hasn’t.

I began painting with determination and a fantasy. I was determined to use the portraits and the words of the subjects as an act of defiance against the lies of an administration leading the American people into unnecessary and illegal wars. The reason this made sense to me was that the people I was choosing to paint — most considered icons of the historical struggle for justice and equality — had all stood up against powerful people and systems which had denied them their rights and dignity. And those powerful forces had used the same techniques — lies, propaganda, fear and patriotism — to deny those rights that they use today.

The fantasy was that I could, by painting the portraits of these courageous people, evoke their spirits in some way to help us now. I imagined the ghosts of Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Mother Jones, Jane Addams, Sojourner Truth, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain, W.E.B. Du Bois, and all the others marching arm in arm, leading millions of people, down Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House to demand the truth about the reasons for the War on Iraq. I imagined them comparing the struggles of their times with issues today so that we would not be so easily manipulated, so easily convinced to give our patriotic approval to causes against our personal interests, the interests of democracy, the environment, and peace. I imagined Frederick Douglass, with his beautiful stentorian voice, addressing the crowd: “…Find out what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong that will be imposed on them.”

Of course, ghosts did not prevent the Iraq War, nor did they prevent a host of environmental, economic, legal, educational, and racial problems since. However, they did propel a remarkable shift in the direction of this project. What began as protest became educational mission. These Truth Tellers can help us, but we have to know their stories.

I realized that I knew little of the true history of this country. I was not alone. Traveling to schools and colleges all over this country I realized that not only students, but teachers, have little idea of our true history. We are unaware of the ongoing struggles for rights and justice in this country, do not know who leads those fights, and have little idea of the forces in our country that make the fight for rights so difficult.

Serendipitously, I met Michele Hemenway, an educator from Louisville, who already was working to teach her students true history. She offered to work with me and develop our curriculum. We are working together now more than ever. And the primary thrust of this educational project is a very simple truth — a democracy without well educated and active citizens can do nothing but fail.

Students in our schools are failing math and reading. That’s important. The more serious problem is that if they are not taught to be engaged citizens, using true history and models of courageous citizenship, we will lose our democracy. Some would say it is already lost and the challenge is to educate our youth to win it back.

And as educators and students we must ask ourselves a tough question, “Whose interests are served by keeping young people ignorant of their own history, unaware of the importance of citizenship and unaware of the inspiring role models from the past and present who could help solve our most pressing problems?” Ignorance is certainly not in the interest of democracy.

When I tell people the name of this project, Americans Who Tell the Truth, I am frequently met with a sardonic look and asked, “Are there any?” Such is the common attitude about the integrity of our political and economic discourse. People are cynical, rightly so, and depressed at the depth of dishonesty all around them.

And I am often asked, “What do you mean by truth anyway? Isn’t truth relative — like your version may be true, but isn’t mine, too?” Most relative “truths” are really opinions. With Americans Who Tell the Truth we are focused on verifiable facts, their remedies and ramifications. For instance: Were women in this country excluded from being full citizens? For how long? Why? How did they finally win their rights? What does that teach us about issues today?

We find it helpful to focus on four aspects of truth.

Foundational Truths: The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution express our ideals of equality and justice, which are defined truths of our nation.

Truth and Trust: Unless people try to tell each other the truth as they know it, they cannot trust each other. And, obviously, any relationship, personal or public, fails without trust.

True Challenges: Unless we are willing to name the true causes of a problem, we cannot fix it. For instance, if we deny that the burning of fossil fuels plays a role in Climate Change, we will not be able to avert climate catastrophe

True Knowledge: If we don’t teach our true history, its shame as well as its nobility, we cannot know who we are. People who don’t know themselves are dangerous to themselves and to others because they act from ignorance and self-serving myths.

As I have spent the past 10 years traveling around this country, talking about the people I’ve painted, about their ethics, history and citizenship, I’ve met an extraordinary number of good people. Engaged citizens in every state are determined to solve issues of inequality and injustice, pollution and poor education, money in the political system and corporate media failing to tell the truths citizens in a democracy need to know. The problems are big, but the number of people wanting them corrected is big, too.

Our cynicism and depression will only increase if we expect government to solve these problems for us. We have to demand change, as Frederick Douglass said, and we have to be willing to do it ourselves. The models of courageous citizenship that make up Americans Who Tell the Truth can help.

One more thing. Through this painting, and traveling and talking I have never been so engaged as a citizen as I am now. Nor have I felt as burdened with the weight of serious problems. But before I started this project, I had never experienced the joy that comes from being a member of a community working for a just and sustainable future. Our deepest happiness is found not in monetary wealth and competition, but in the shared spirit of working together for a good cause, for the ideals of this country and for peace.

Americans Who Tell the Truth offers a link between the community of people who struggled for justice in our past and the community of people who are doing it now. To participate in that struggle can be very hard, but it is also a place to find deep friendship, shared courage, respect and dignity. And, only by participating in that struggle will we find hope, or deserve to.

— Robert Shetterly

The second strong feeling — the first being horror — I had on September 11 was hope, hope that the United States would use the shock of this tragedy to reassess our economic, environmental, and military strategies in relation to the other countries and peoples of the world. Many people hoped for the same thing — not to validate terrorism, but to admit that the arrogance and appetite of the U.S., all of us, have created so much bad feeling in many parts of the world that terrorism is inevitable. I no longer feel hopeful.

If one looks closely at U.S. foreign policy, the common denominator is energy, oil in particular. The world is running out of oil. Political leadership that had respect for the future of the Earth and a decent concern for the lives of American and non-American people would be leading us away from conflict toward conservation and economic justice, toward alternative energy, toward a plan for the survival of the world that benefits everyone. We see hegemony and greed thinly veiled behind patriotism and security. We get pre-emptive war instead of pre-emptive planning for a sustainable future.

The greatness of our country is being tested and will be measured not by its military might but by its restraint, compassion, and wisdom. De Toqueville said, “America is great because it is good. When it ceases to be good, it will cease to be great.” A democracy, whose leaders and media do not try to tell the people the truth, is a democracy in name only. If the consent of voters is gained through fear and lies, America is neither good nor great. Nor is it America.

I began painting this series of portraits — finding great Americans who spoke the truth and combining their images with their words — in 2002 as a way to channel my anger and grief. In the process, my respect and love for these people and their courage helped to transform that anger into hope and pride and allowed me to draw strength from this community of truth tellers, finding in them the courage, honesty, tolerance, generosity, wisdom and compassion that have made our country strong. One lesson that can be learned from all of these Americans is that the greatness of our country frequently depends not on the letter of the law, but the insistence of a single person that we adhere to the spirit of the law.

My original goal was to paint fifty portraits. I’ve gone beyond that and have decided to paint many more. The more I’ve learned about American history — past and present — the more people I’ve discovered whom I want to honor in this way. The paintings will stay together as a group. The courage of these individuals needs to remain a part of a great tradition, a united effort in respect for the truth. These people form the well from which we must draw our future.

— Robert Shetterly