What's New

Rob’s Report from Bozeman

Robert Shetterly was invited to Bozeman, Montana for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, 2015. He spent four days there, visiting schools, working with students at Montana State University, and giving a public talk for the citizens of Bozeman.

After the visit, Ariel Donohue, one of the event organizers, said this about Rob’s visit:

“Rob has the incredible ability to inspire people of all ages and teach universal lessons of kindness, fairness, and justice. During his visit, Rob spoke to 2,000 students and community members, in settings as large as school assemblies and public lectures and as small as intimate group dialogues and discussions. Rob challenged students in our community to think critically about the world around them and to speak out in support of what they know is right. Following Rob’s series of presentations, we heard the same message from the various schools and groups he visited: ‘Rob’s visit changed lives.’ His portraits and his words move beyond traditional history, art, and writing lessons; he teaches us to question what we hear, to be courageous in our actions, and to find ways to make positive impacts in our communities.”

I was invited to be the keynote speaker for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day at an event sponsored by Montana State University and Humanities Montana (a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities), plus of host of other local organizations and people. Before going I had suggested that the sponsors arrange for me to talk in local schools. It turned out that my schedule was very busy with some wonderful moments for AWTT.

I had been warned that Montana is a “red” state and I may want to “be careful” with some of my content; don’t speak a lot about war and politics. I found it wryly amusing that I was being asked to honor MLK, Jr., and censor myself. I didn’t. Any kind of censorship seemed not only insulting to Dr. King but patronizing to the people of Bozeman. And, quite the contrary, I was promoted enthusiastically by school principals as a person with an important message about rights and citizenship.

Part of the appeal of going there for me was the geography. Bozeman is on a high, wide plain in south central Montana, very flat, 5000′ elevation, surrounded in all directions by dramatic mountain ranges – the Bridgers, the Gallatins, Madisons, Crazies. There was little snow on the ground in Bozeman, which is unusual, but lots on the mountains, setting up beautiful subtle color harmonies between the the wide ochre and golden plains and the steep black and white mountains. Everywhere the mountain colors were repeated in miniature by the omnipresent magpies squawking from every tree and bush. At the end of my trip I was driven south to the northern section of Yellowstone and saw lots of bison, pronghorns, elk and mule deer, and magnificent clouds of steam billowing from the bubbling hot springs. So often I give talks about protecting the environment; it was stunning to be in a place of such powerful majesty, a place that one would think it obvious that to diminish or desecrate it in any way would be criminal. And yet, Bozeman, an economically thriving, growing community, is sprawling, spreading out with condos and malls onto the plains that had been wheat and grazing land. The university’s enrollment is growing. People seem very excited about business expansion. How to think about this? What to say? Economic expansion, sprawl, higher incomes, joy in the chamber of commerce, loss of habitat.

My first full day began early with a trip to Bozeman High School (100 students +) followed by a talk at Chief Joseph Middle School (750 students). I was pleased at how well the principals who introduced me framed the mission of AWTT and the importance to students of our message of engaged citizenship. I was brought there to talk about Dr. King and civil rights, but I began each session with the portrait of Chief Joseph. First, I wanted to honor the local population of native peoples – in this case Crow and Blackfeet – and, second, to use his quote to get young people to think about the legacy of power and privilege.

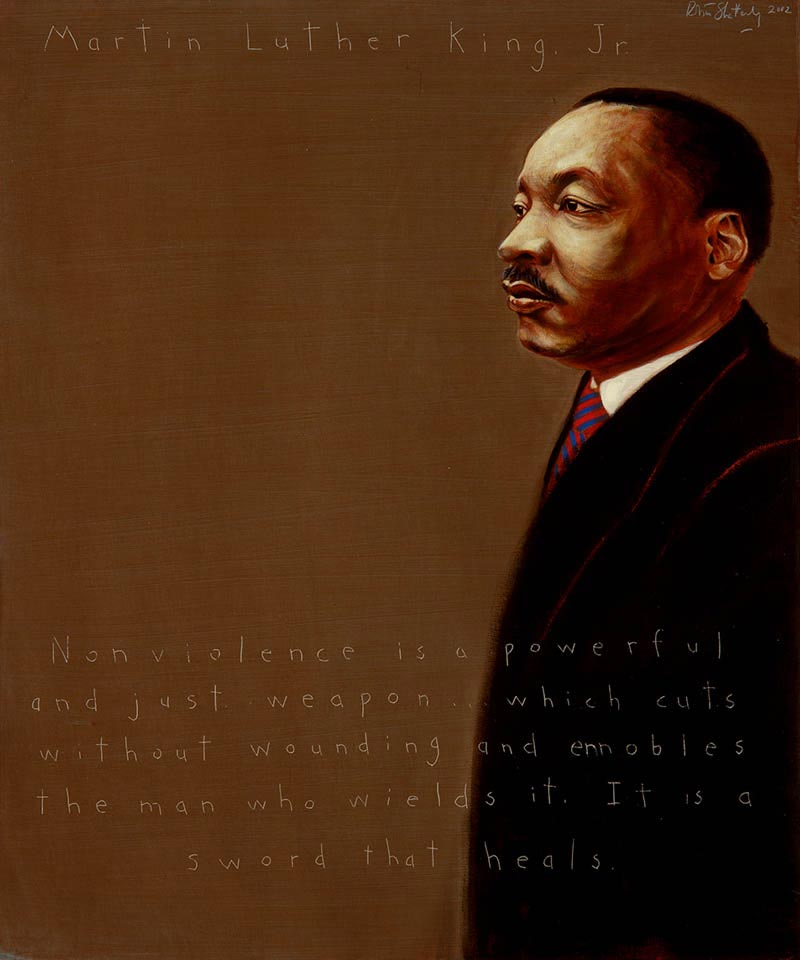

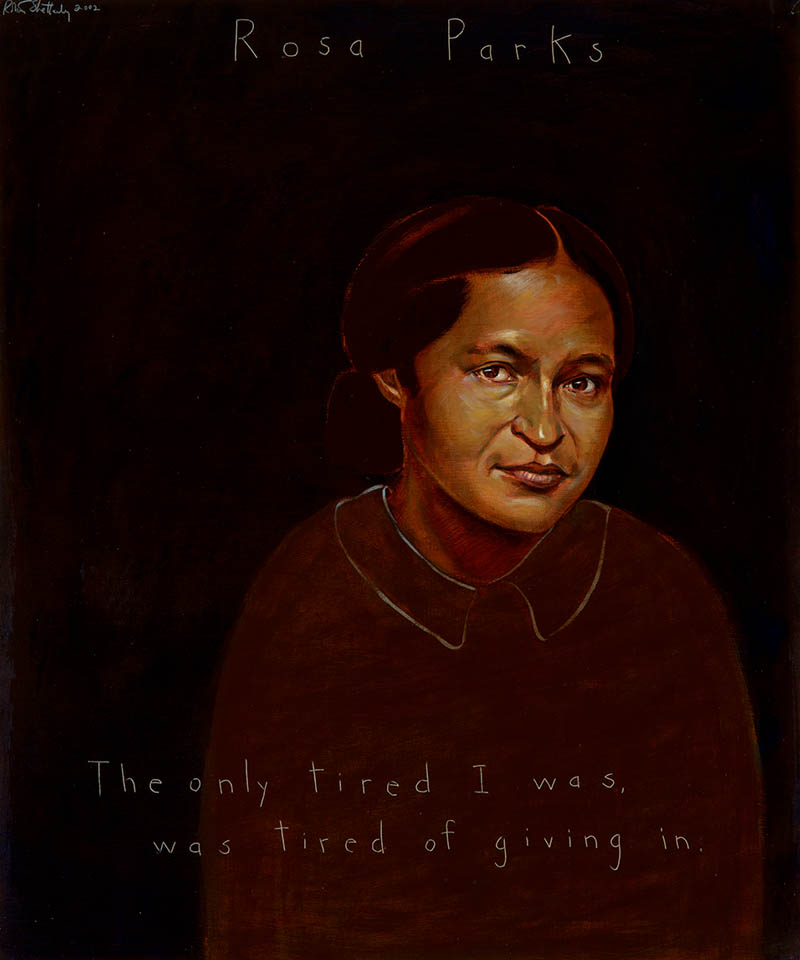

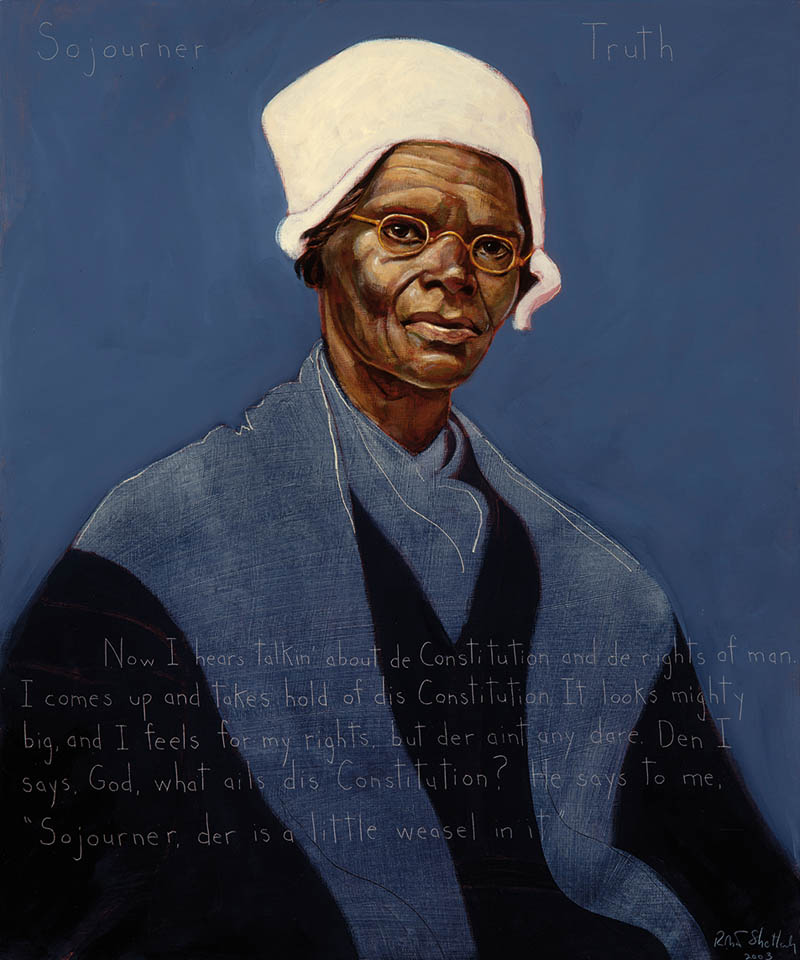

Chief Joseph said, “I have asked some of the great white chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me.” I recited the quote to each group and asked them what the chief meant. Where did the authority come from? Was it legitimate? Every group of students immediately said that the basis of the “authority” was power and racism and that it had no moral or legitimate basis. Using that, I began a discussion of our civil rights struggles particularly highlighting Rosa Parks, Barbara Johns, Claudette Colvin, Sojourner Truth, and MLK Jr. In every school I was impressed at how responsive the students were, asking lots of important questions, including, in one school, “Have you painted any white people?” I have painted lots of white people, but that question enabled a discussion about how it is often the marginalized and disenfranchised in a society who have to lead the fight for justice and equality.

That evening I was welcomed to Bozeman at a reception at Wild Joe’s Coffee Shop (one of the sponsors of my visit). Wild Joe’s had twelve posters of civil rights heroes on the wall. Good crowd. I spoke very briefly about how courageous engagement by citizens is the essential determining factor in maintaining democracy – more important than any of the institutionalized supports. I quoted from Helen Keller, Mother Jones, and Frederick Douglass. There were so many great activists in the crowd . . . as seems to be the case anywhere. I often feel awed by the efforts of these people, and they are so grateful that AWTT is keeping this history (theirs!) alive.

The next morning, January 20th, I spoke first at the Sacajawea Middle School. I had mixed feelings about speaking in schools named for Chief Joseph and Sacajawea. On the one hand, naming a school for a famous native American is a bit like naming a housing development Maple Grove after cutting down all the maples to build the houses. But, on the other, at least the names preserve the presumption of honor. However, the naming of the school does nothing to change the equation of power. The only thing worse would be General George Custer Middle School.

Next stop was the MSU honors college. I was asked to speak about contemporary truth tellers, so I featured Michelle Alexander, Tim DeChristopher, Florence Reed, and then purposely brought up Edward Snowden as a way to prompt dialogue.

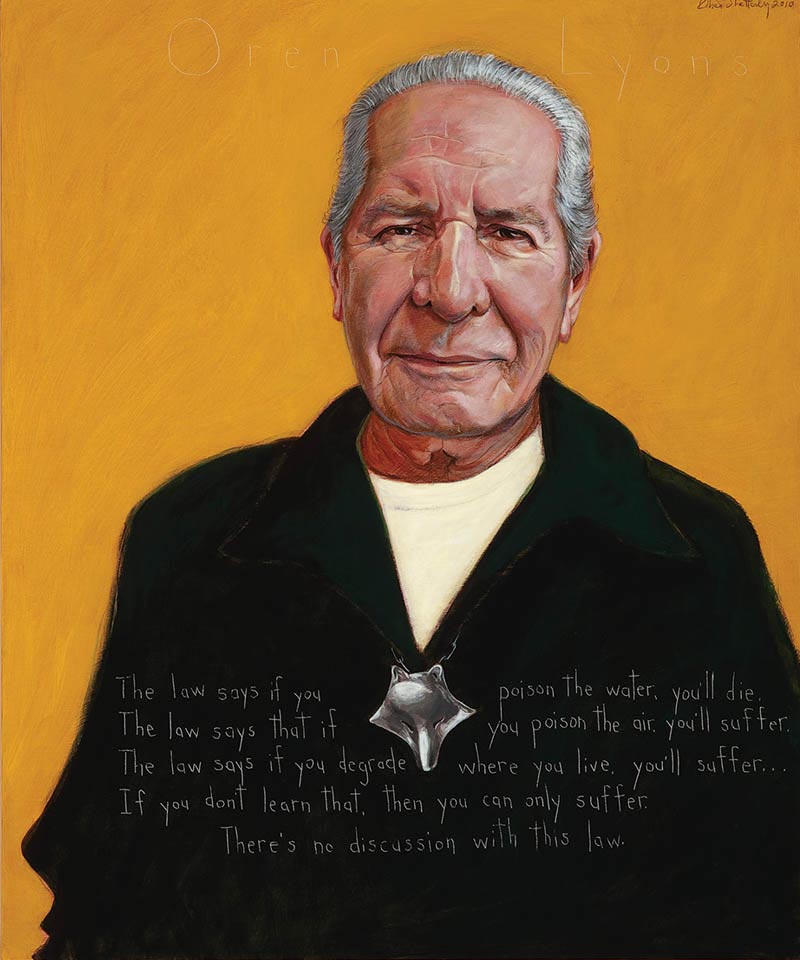

That evening was the public keynote address at the Crawford Theater. My intention was to honor Dr. King but to also make it clear that many other people played decisive roles in civil rights who are overlooked or forgotten. I began with the image of Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga tribe, and how he told me about the Doctrine of Christian Discovery. I wanted to make sure that my audience understood the centuries-long shaping of the ideas that justified racism, imperialism, colonialism, objectification and white supremacy. I told stories about Barbara Johns and Charles Hamilton Houston. I discussed what made Dr. King a true radical, that is, insisting on going to the root of the problem, refusing to be comfortable with reform, insisting that racism is bound up with materialism, poverty and militarism and that only a revolutionized economic system would solve these problems. I stressed the difference between cultural racism (much better than it used to be), and structural racism (still entrenched and perhaps worse).

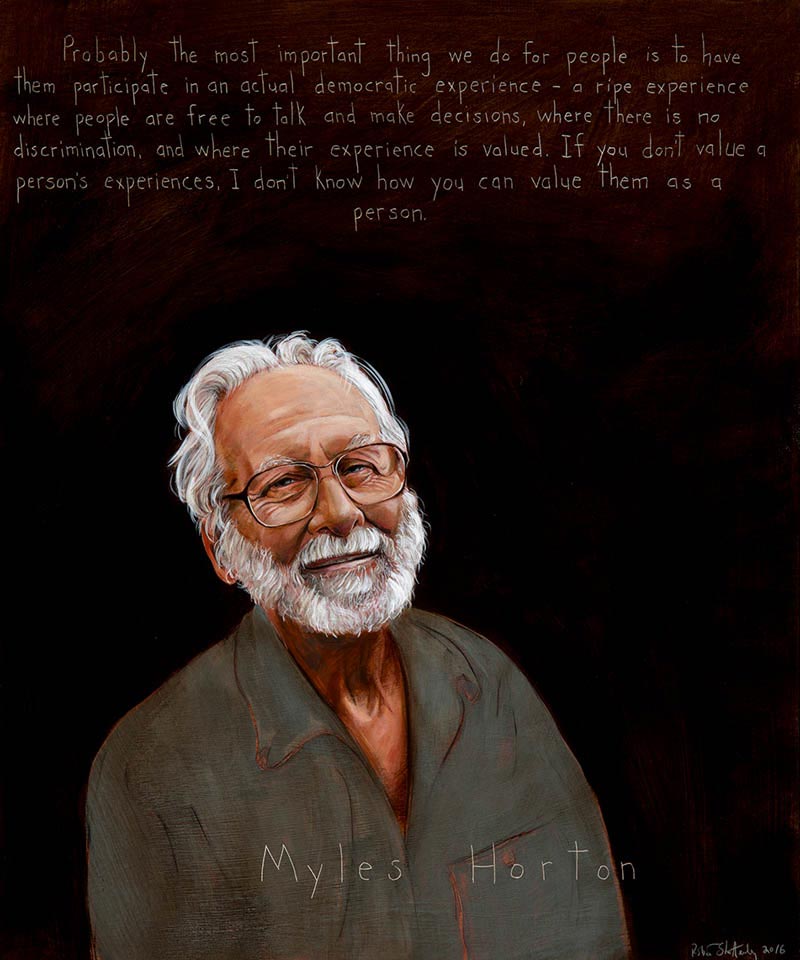

After the talk, I met Mike Clark, who was director of the Highlander Center in Tennessee for fifteen years, following Myles Horton. He connected me with Myles’ daughter, Charis, who will help me find images of Myles to paint his portrait, which I’ve wanted to for a long time.

A man who works with the native tribes in Montana told me that the elephant in the room when talking about African American civil rights is the ongoing racism toward Native Americans. I later talked to several people about beginning the process of seeing if something like Maine’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission might work in Montana. They are exploring it.

The next morning, January 21, I was in the 6th grade at the Anderson School where a great teacher, Stephani Lourie, had her students each reporting on one of the civil rights portraits and doing art projects about that person. Three of the students stood up and delivered their reports to me. Very impressive. Later I spoke to the entire middle school there.

After Anderson I was taken to the Headwaters School, a private middle school. Instead of talking to hundreds of kids, here I was in an informal setting with about forty. Lots of give and take. This was one of the best teaching moments of the whole trip – partly a function, I think, of the smaller group, partly a function of private education that emphasizes critical thinking.

Then we were off to the Bozeman public library to meet with fifty homeschooled kids. Only three tired mothers showed up with seven little kids – ages four to seven. We got in a circle (with the mothers), and I asked the kids to tell me what was fair and what was not. A seven year old girl, Alicia, said, “It’s not fair when some kids get a Samantha doll and some don’t.” The core issue! Then we talked about what’s scary and what we can do about fear. I told stories of Samantha Smith and Claudette Colvin in a very simple way. Perhaps one of the most engaging exercises I did with them was to simply show a portrait, not identifying the person or the issue but asking, “What do you think this person is feeling or thinking?” So these little kids said John Lewis was confused, angry, tired, determined. Lily Yeh was compassionate. Tim DeChristopher was “looking one way, but thinking something else.” Ella Baker was weary, wise, warm.

Later that day I met for three hours with the Leadership Institute and the Sustained Dialogue student groups at MSU. I was asked to talk about leadership styles. I focused on grassroots leadership, using Lily Yeh and Bob Moses. In the Sustained Dialogue circles, the questions being discussed were mostly about identity and privilege. I mostly listened, but mentioned at the end that even people confronted by cultures of powerful white privilege can create their own privilege through sustained courage and passion. Look at Sojourner Truth. Nobody knows or cares about the white people who owned and employed her. We know and honor her, an illiterate former female slave. Where did her privilege come from to be such a respected leader and orator?

More comments from Bozeman

From a 17 years old high school student: “I can’t even begin to describe how much Robert Shetterly’s message meant to me. His link from the Christian doctrine to structural oppression today was phenomenal, and his artwork beautiful . . . continuing to spark conscious thoughts regarding issues of race and power. The event was phenomenal.”

From a middle school Social Studies teacher: ” . . . eighth grade students had their semester final in U.S. history that same afternoon that Robert gave his presentation to the schools. Some of them wrote wonderful paragraphs about whose hands they would have on their shoulders when they needed to speak out against an injustice. Robert empowered them. What a gift he gave them, and to reach so many students was wonderful!

From the principal at one of the schools in which Rob spoke (to 700+ students): “Mr. Shetterly, thank you for such an amazing message. Our students are truly blessed to attend school in a district where they are exposed to such genuine people as yourself.”