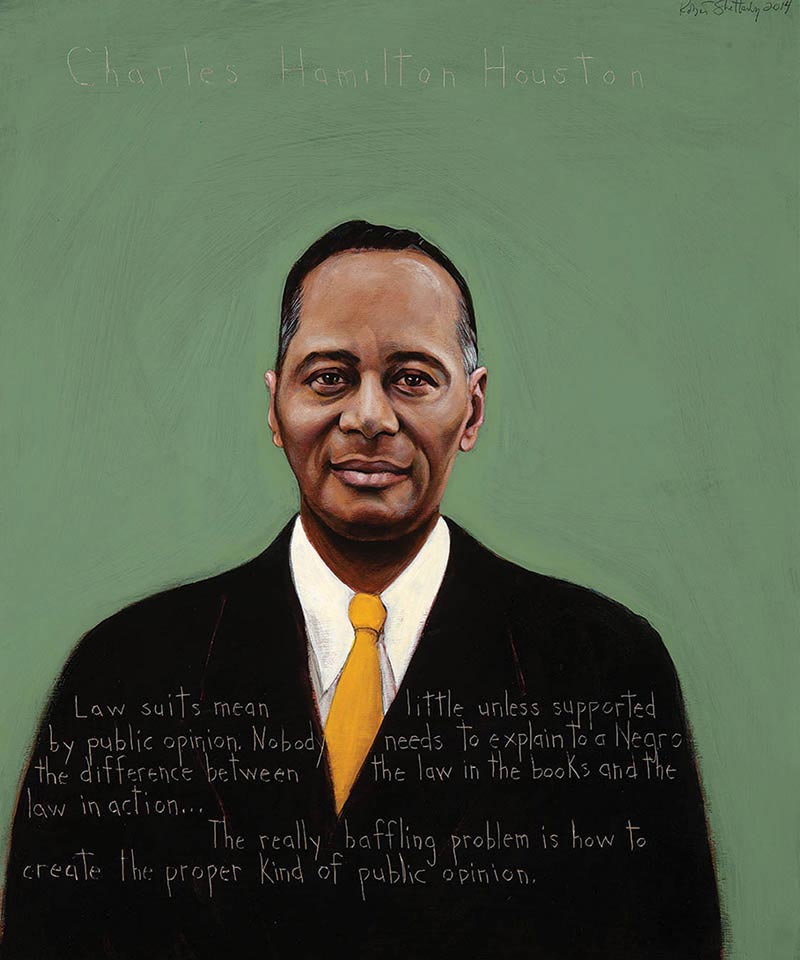

Charles Hamilton Houston

Lawyer, Architect of the Civil Rights legal strategy : 1895 - 1950

“Law suits mean little unless supported by public opinion. Nobody needs to explain to a Negro the difference between the law in the books and the law in action. … The really baffling problem is how to create the proper kind of public opinion.”

Biography

“A lawyer’s either a social engineer, or he’s a parasite on society,” wrote Charles Hamilton Houston. Though trained as an attorney, he proved to be a formidable social engineer, establishing the strategy that ultimately took down the legal foundations of segregation in the United States, particularly in the field of education. Houston worked in private practice and served as the lead attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He was also an administrator and law professor who was instrumental in the successful effort to gain accreditation for the Howard University School of Law.

Houston, the son of William L. Houston and Mary Hamilton Houston, was born on September 3, 1895 in Washington, D.C. Houston’s father, an attorney, and. his mother, a former teacher, were part of a strong middle class community in Washington when the city was a magnet for African Americans seeking top tier educational and employment opportunities. Houston benefited from these opportunities. He attended Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, one of the nation’s top public schools at that time. Houston went on to Amherst College, where he was the only African American student in his class, finishing his undergraduate degree in 1915; he completed his LL.B. in 1922, and his S.J.D. (doctor of juridical science) at Harvard in 1923. Houston was both the first African American elected to the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review, and the first African American to earn an S.J.D at the university.

In the time between Amherst and Harvard, Houston fought in World War I. He was in the first class of African American men trained to be Army officers at Fort Des Moines, Iowa in 1917 (also the site where the first female Army officers would train during WWII). Commissioned as an infantry first lieutenant and then as a second lieutenant, he was shipped to the European theater. Unfortunately, Houston’s time of service came during the nadir of U.S. race relations, and his experiences in the Army were hallmarks of that period (roughly 1877-1920). Serving as a judge advocate, Houston was in a position to see the legal injustices suffered by African American service members directly. Segregation was firmly enforced by the Army. African American officers were treated with disrespect, denied the privileges afforded other Army officers, and constantly abused. Houston recounted a story of nearly being lynched in France by white American soldiers because they didn’t like seeing an African American officer interacting with a white French woman. “The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

Houston kept his word. In 1924, after finishing at Harvard and a year of additional legal study at the University of Madrid, he joined his father’s law practice in Washington, D.C. He also served as an administrator and a professor at Howard University’s relatively new law school. Through Houston’s leadership, the law school was accredited by Association of American Law Schools and became a beacon of justice, crafting the legal arguments in favor of civil rights and training a large number of African American attorneys, including the future legal luminaries Thurgood Marshall and Oliver Hill. Houston used his position at the law school to impart to his students a vision for dismantling legalized segregation. His teaching and his strategy would have great effect.

In 1935, Houston took a leave of absence from his private law practice to serve as legal counsel for the NAACP. This move provided Houston with an opportunity to begin to implement the legal strategy he designed to combat segregation. As noted by historian Genna Rae McNeil, Houston sought to use the court system’s reliance on stare decisis to establish legal precedents that would erode the underpinnings of racial segregation laws. The end goal was to seek to overturn the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which enshrined the constitutional doctrine of “separate but equal.” And it was in 1938 when Houston and his team of attorneys won the case Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada. In that case, African American student Lloyd Gaines sought admission into the University of Missouri law school. The state offered to pay for Gaines’s tuition to attend a law school out of state, but the Supreme Court determined that Missouri had to provide Gaines, a qualified student, with a legal education; because Missouri did not have a law school for African Americans, Gaines had to be admitted to the all-white University of Missouri, which had the state’s only public law school.

Though Houston’s tenure with the NAACP ended in 1940, he continued to work with other attorneys on cases that attacked the “separate but equal” doctrine. With each victory, they inched closer to overturning Plessy v. Ferguson. In Steele v. Louisville and Nashville Railroad et. al., Houston argued that unions had to represent their members (as well as non-members in that field) regardless of race, and the Supreme Court agreed. He assisted the attorneys who argued that racially restrictive housing covenants could not withstand scrutiny under the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, and the Supreme Court, in the cases of Shelly v. Kraemer and Hurd v. Hodge, agreed again. Each successful case created new precedents that weakened segregation’s legal foundation.

Unfortunately, Houston did not live to see Plessy v. Ferguson overturned. On April 22, 1950, at age fifty-four, Houston suffered a fatal heart attack. His paternal grandfather, Thomas Jefferson Houston, a minister and former conductor of the Underground Railroad who was the first in the family to use arguments to achieve difficult goals, would have been proud of his grandson’s accomplishments. Houston’s students, Marshall, Hill, and others continued expanding the campaign that their teacher had begun, heeding his words as they fought to end legalized racial segregation: “There is no such thing as ‘separate but equal.’ Segregation itself imports inequality.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.