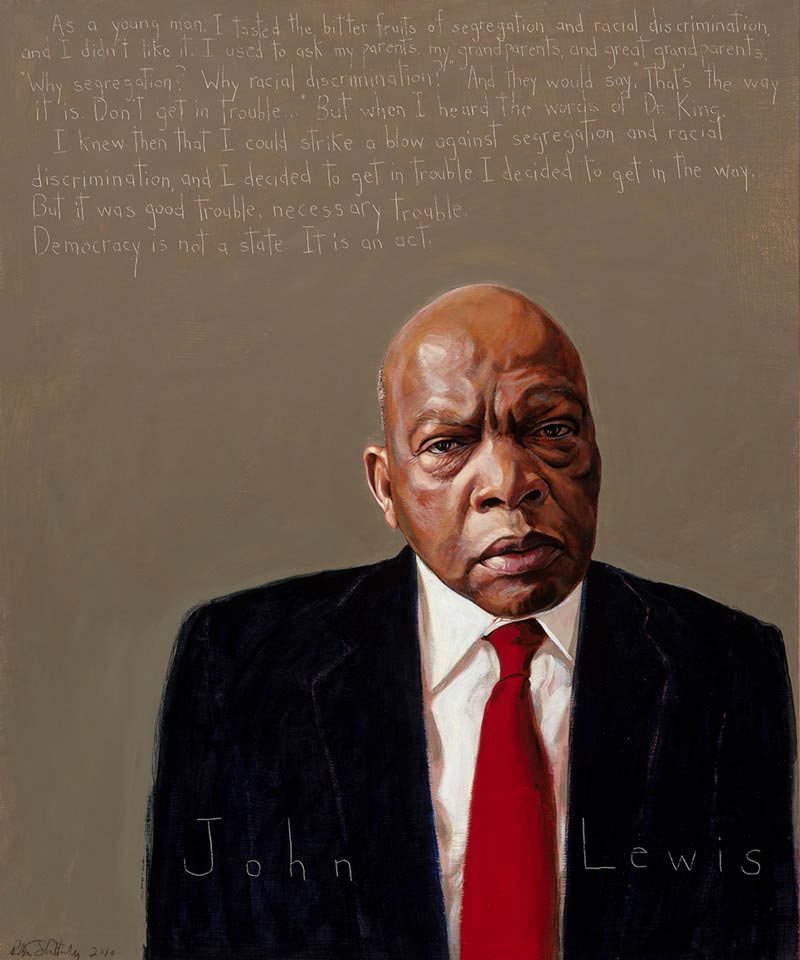

John Lewis

Civil Rights Activist, Congressman : b. 1940 - 2020

“As a young man I tasted the bitter fruits of segregation and racial discrimination, and I didn’t like it. I used to ask my parents, my grandparents, and my great grandparents, ‘Why segregation? Why racial discrimination?’ And they would say, ‘That’s the way it is. Don’t get in trouble. …’ But when I heard the words of Dr. King, I knew then that I could strike a blow against segregation and racial discrimination, and I decided to get in trouble. I decided to get in the way. But it was good trouble, necessary trouble. Democracy is not a state. It is an act.”

Biography

John Lewis, the son of Alabama sharecroppers, was inspired as a teenager by meeting the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Lewis trained in non-violent methods and organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters while he was a student at Fisk University. He continued to “strike blows against segregation and racial discrimination” for another sixty years.

At the age of twenty-one, Lewis joined the “freedom riders,” risking his life and getting severely beaten by angry mobs. Two years later he became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and organized student activism in the civil rights movement. He was the youngest speaker at the 1963 March on Washington and the most explicit in terms of racial demands. In 1965, as Lewis and Hosea Williams were leading more than six hundred peaceful protestors over the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to demonstrate the need for voting rights, state troopers attacked the marchers, an event that later became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The media revealed the cruelty of this event and the southern segregation that lead to it, helping to hasten the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Despite more than forty arrests and serious injuries, John Lewis remained an unrelenting advocate of nonviolence. Serving as the representative in the US House of Representatives for Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District from 1987 to 2020, his speeches, writings, and voting record show his commitment to a global vision in which all people can share in the wealth of the Earth. In the prologue to his autobiography, Walking with the Wind, Lewis observed, “Children holding hands, walking with the wind. That is America to me – not just the movement for civil rights but the endless struggle to respond with decency, dignity and a sense of all the challenges that face us as a nation, as a whole. That is the story of my life, of the path to which I’ve been committed since I turned from a boy to a man, and to which I remain committed today. It is a path that extends beyond the issue of race alone, and beyond class as well. And gender. And age. And every other distinction that tends to separate us as human beings rather than bring us together. That path … an ideal I discovered as a young man has guided me like a beacon ever since, a concept called the Beloved Community.”

John Lewis has written: “We, the men, women, and children of the civil rights movement, truly believed that if we adhered to the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence, we could help transform America. We wanted to realize … the Beloved Community, an all-inclusive, truly interracial democracy based on simple justice, which respects the dignity and worth of every human being.”

John Lewis’s daily conduct, whether it was on the floor of the House defending or challenging a proposed bill or speaking to a group of college students, testifies to his unwavering belief in the utilization of the concept of the Beloved Community. He is known for being one of the most courageous members of Congress, ever willing to speak out for peace and justice. He was the first major House of Representatives figure to call for the impeachment of George W. Bush on the grounds that the president “deliberately, systematically violated the law” in authorizing illegal wiretapping of American citizens. He pointed out that “He is not King; he is president.”

Representative Lewis was a passionately outspoken critic of the Bush administration’s military occupation of Iraq. The conclusion of the speech Lewis delivered on the floor of the House on March 19, 2007, regarding supplemental funding for the war, demonstrates his his dedication to democracy: “Tonight I must make it plain and clear that as a human being, as a citizen of the world, as a citizen of America, as a Member of Congress, as an individual committed to a world at peace with itself, I will not and I cannot in good conscience vote for another dollar or another dime to support this war.”

On March 22, 2007, John Lewis received a Backbone Award for his efforts to convince Congress to oppose the Bush administration’s actions in the Middle East. When asked by Backbone committee members how he keeps going when so many people are stepping aside, he replied that the struggle to create the Beloved Community, a just society “at peace with itself,” is a struggle of a lifetime and that he would continue to stand up for what is right as long as he could move and breathe.

John Lewis died on July 17, 2020, while still serving in the U.S. Congress, “Making good trouble” to his last breath.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.