What's New

What Would Clyde Do? Why I Painted Clyde Kennard

Chances are you haven’t heard of Clyde Kennard, an unsung hero and martyr of the Civil Rights Movement, a man of great wisdom, compassion, gentleness, and determined courage. Until a few months ago, I hadn’t either. Then a colleague told me a remarkable story about a man set on showing southern Mississippi white people that their culture would be better for them if they integrated. A man whose claim on the American Dream was so deserved that in 1960 a governor, a college president, former FBI agents, police, and members of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission decided to frame him and sentence him to Mississippi’s brutal Parchman Prison for seven years to make sure his dream was not realized. (Read his story here.)

Why is it valuable to know his story? Is it to let his friends and family know that he is not forgotten? Not really. He has no direct surviving family. His friends know his story. So I ask myself the question: What difference has it made to me to learn about Clyde, to paint his portrait? I’ll try to answer that in several ways.

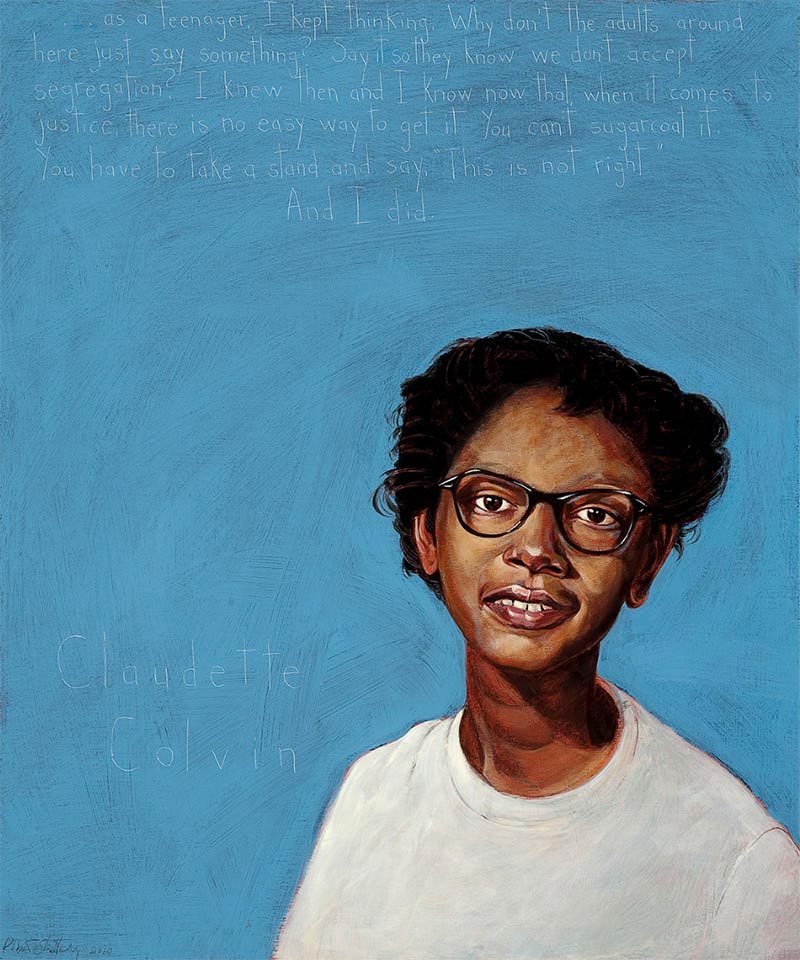

The day after unveiling Clyde’s portrait, I had the opportunity to speak with about fifty 11th grade students at Wilson High School in Washington, DC. I wanted to demonstrate to them the kind of work that AWTT does—what we call Narrative Activism—by telling them the story of Claudette Colvin. In 1955, nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat, Claudette, a fifteen-year-old student, refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, when the bus driver ordered her to give up her seat to a white person. When the bus driver made this demand, she asked herself: What would Harriet Tubman do? The answer: Harriet wouldn’t have moved. And Claudette didn’t.

As I began to tell this story, I said to the class, I doubt that you know about Claudette Colvin, but you all know about Rosa Parks, right? Wrong. Not one of those fifty students, over half of them African American, could tell me who Rosa Parks was.

Does that matter? I suspect that most of you would say, Yes! If you don’t know about Rosa Parks, you can’t tell yourself a narrative about civil rights history in the U.S. If you don’t know Rosa Parks, you don’t have an essential role model of courage who shows you how to do what’s right when the law is wrong. If you don’t know about Rosa Parks, you probably don’t know how important civil disobedience is to maintaining justice. If you don’t know about Rosa Parks, you might think that the entire Civil Rights Movement was carried on the shoulders of only one monumental man, Martin Luther King, Jr.! The Wilson High School students had heard of Dr. King. I know because I asked.

But if it’s important to know Rosa, why is it less so to know Claudette or Clyde? Or Barbara Johns? Or Fannie Lou Hamer? Or John Lewis?

Most people growing up in the world today, and not only those in urban environments, have little idea that their health and prosperity, their future, depends on the health and prosperity of the natural world, the Earth. The world that they see is degraded, decimated, polluted, and paved over. Often the small areas of green that are present are more depressing than uplifting or consoling—some scraggly bushes, a damaged tree, unhealthy patches of grass, all adept at snagging litter. This civilized landscape may be visited by a few gray squirrels, crows and English sparrows. If there is water, it is likely industrial, a place where tankers dock, or a creek straightened into a canal and banked with refuse.

Wildlife is more likely represented by a rat than a heron. If this is the experience children have of nature, what is the lesson? They are probably not being taught to believe that their lives depend on the health of these natural systems. How could it? The environment is obviously unhealthy. If nature mattered, surely adults wouldn’t treat it like that.

Similarly, in most schools in this country our children are taught an American Civil Rights history that is barren, degraded, depopulated, and paved over. They are presented with a vast empty plain except for one surprising, towering tree of Giant Sequoia dimensions, Martin Luther King, Jr. A peaceful giant. Scattered here and there are a few nearly indistinguishable shrubs—Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and maybe Frederick Douglass.

And even if the students know the names of the shrubs, they often get them confused: Oh yes, Rosa Parks was a conductor on the railroad. What railroad? I don’t know. What they are not being taught is that knowing the richness and diversity of our Civil Rights Movement, the fact that it was made possible by the actions of thousands of people acting together and apart, can be as important to their health, prosperity, and future as Nature.

Dr. King, with his stature of a mythic giant, is less a role model than a god. If he is a god, he is not a person you or I or a ten-year-old can aspire to be. He can only be worshiped as a savior. And then we pray for another savior. We are taught to express awe and gratitude, but not emulation.

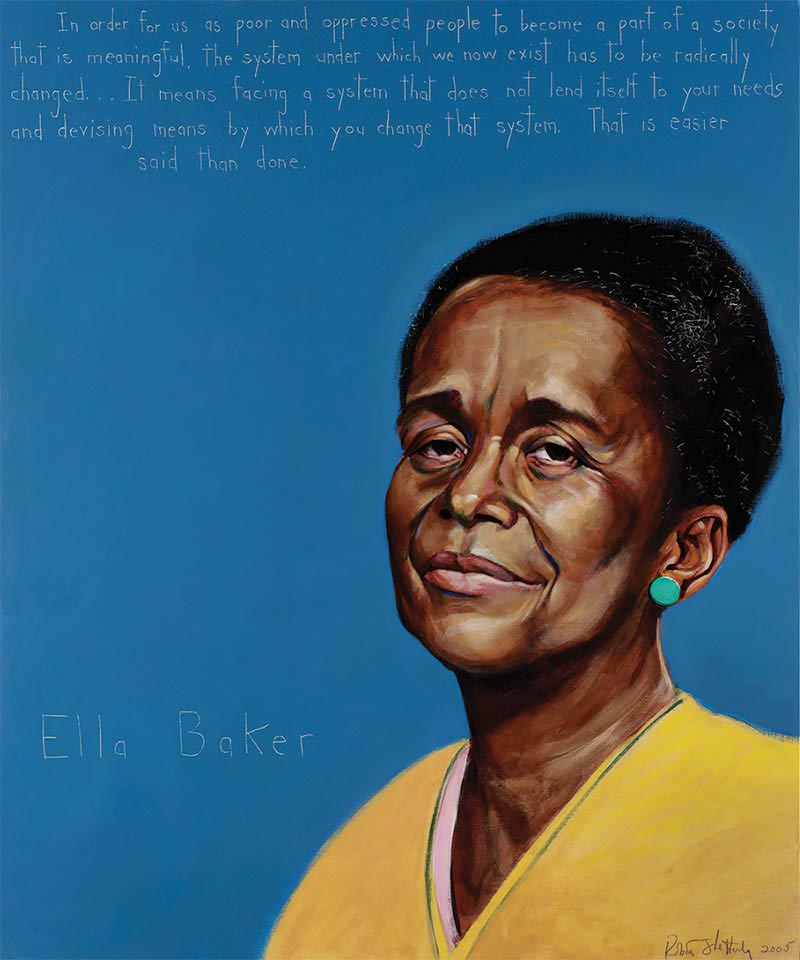

When, on the other hand, we are taught about all the trees in the forest—the Clydes and Rosas, Barbaras and Fannies, Bobs and Ellas, Medgars and Sojourners, Dianes and Johns—we see that each of us can be a tree if we are willing to act with courage for a cause that is right. We learn that change did not happen because of one tree. In fact, change will not happen because of only one tree.

But, to answer my original question, what diference has Clyde’s portrait made to me? Because I painted Clyde I know much more intimately that for every person who lived to see some progress in civil rights, there was another, often forgotten, who died trying. This doesn’t depress me. It gives me a fine appreciation for the price of justice. And it gives me hope. We despair waiting for a savior. But we have hope when there are stories everywhere of courageous actions by people a lot like us who climbed the mountain together.

Around anyone who acts with courage to create justice, a community forms. Moral courage attracts those hungry for it.

So, because I painted Clyde Kennard, I now know of fifty more people, deeply inspired by him, who have continued his legacy of working against racism. I read about a handful of people who dedicated a portion of their lives to freeing him from prison and then to having him exonerated after he died. Because of these people my life is richer, my community has grown. A community offers both support and expectation. And to say your community has grown is also to say your heart has grown; when we have strong community and full hearts, we are not easily intimidated by the purveyors of violence and hatred and fear.

Sitting on that bus, Claudette Colvin asked, What would Harriet do? Now I can also ask, What would Clyde do?