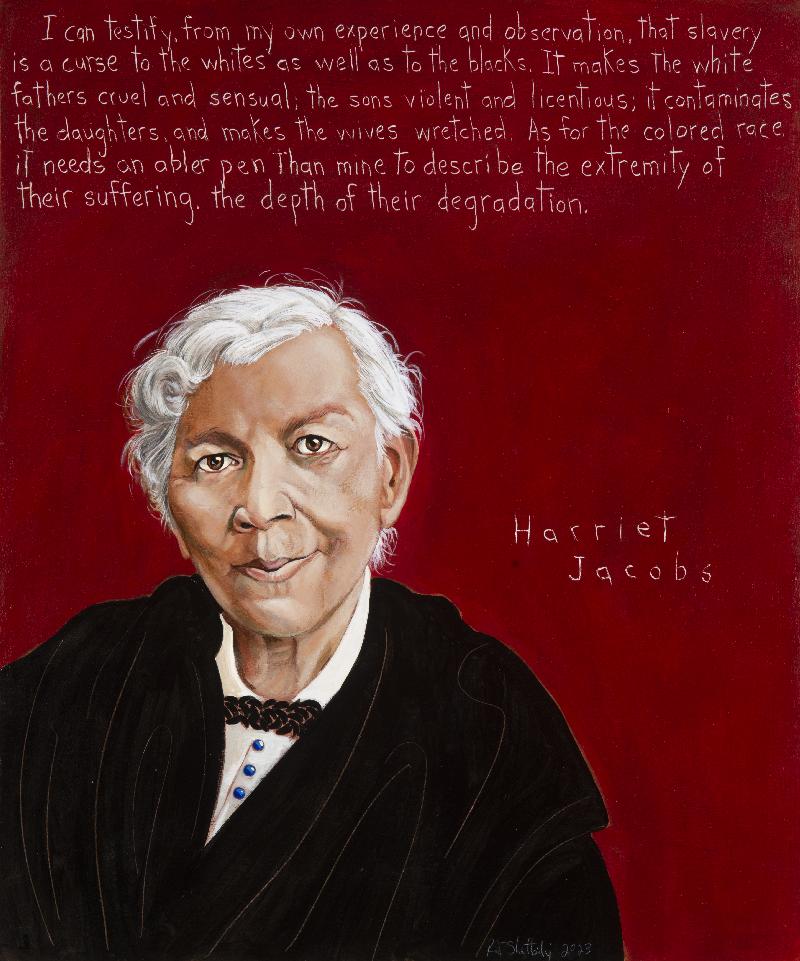

Harriet Jacobs

Author, Abolitionist, Teacher: 1813 - 1897

“I can testify, from my my own experience and observation, that slavery is a curse to the whites as well as to the blacks. It makes the white fathers cruel and sensual, the sons violent and licentious; it contaminates the daughters, and makes the wives wretched. As for the colored race, it needs an abler pen than mine to describe the extremity of their suffering, the depth of their degradation.”

Biography

- fled North from slavery after seven years in hiding

- wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

- worked in the abolitionist movement

- founded the Jacobs School in Alexandria, Virginia, a school for freed people (1860’s)

- worked for relief organizations in Savannah, Washington, D.C. and Boston

Harriet Ann Jacobs was a writer, abolitionist, and spiritual leader who self-liberated from slavery and went on to write an account of her life, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which became instrumental to the abolitionist movement.

Harriet was born in Edenton, North Carolina, to enslaved parents in 1813. Orphaned early, she and her younger brother, John, lived in slavery with their maternal grandmother, Molly Horniblow. Throughout her life, Harriet’s grandmother would be profound source of strength, faith, love, and the resilience of family in impossible conditions.

During Harriet’s young life, she was enslaved to Elizabeth Horniblow, who taught Harriet to read, write, and sew. When she was six years old, Elizabeth died, and rather than freeing Harriet, she left her to her young niece, Mary Matilda Norcom.

Harriet moved to the Norcoms’ house, where she faced years of sexual harassment from Mary Matilda’s father, Dr. James Norcom, and emotional abuse from his wife. Seeking to avoid both the foul words that Dr. Norcom whispered in her ear and his vicious threats and bribes, Jacobs entered into a relationship with another white man, Samuel Sawyer, a lawyer and later a member of the U.S. Congress. With Sawyer she had a son, Joseph, born in 1829, and a daughter, Louisa, born in 1833. Knowing Dr. Norcom would be furious, Harriet hoped he would sell her and her children to Mr. Sawyer, who promised to make them free. Sawyer never made good on his promise.

When Dr. Norcom continued his abuse and began to threaten to sell her children, Jacobs went into hiding. She spent her days and nights in her grandmother’s attic crawl space, measuring nine feet long, seven feet wide and three feet high, barely high enough to sit in – “total darkness and stifling air,” she wrote. Season after season, from the bone-chilling cold to the bugs to the stifling, humid heat, she watched her children grow up through peepholes drilled in the roof. She remained concealed in her grandmother’s attic crawl space for nearly seven years. Through near-death experiences, despair, and the uncertainty of the future, Harriet practiced casting a vision of freedom for herself and her children.

Harriet referred to slavery as the “Demon of Slavery” and recognized the ways in which it corrupted the souls of the enslavers even as it wrought devastation in the lives of the enslaved. She was an advocate for the casting out of the Demon of Slavery for the sake of collective liberation, writing: “reader, did you ever hate? I hope not. I never did but once; and I trust I never shall again. Somebody has called it ‘the atmosphere of hell’; and I believe it is so.”

After seven years in hiding, Jacobs escaped north on a ship. She found employment in New York City with the writer Nathaniel Parker Willis and his wife, Mary Stace Willis, caring for their daughter, Imogene. After Mary Stace died in childbirth, Willis married Cornelia Grinnell who soon gave birth to Grinnell Willis in 1848 and Lilian Willis in 1850.

The fugitive slave law of 1850 forced Jacobs into hiding when Mary Matilda Norcom and her husband, Daniel Messmore, fell on hard times and set out to pursue Harriet. To end the persecution, Cornelia Willis paid the Messmores, who then agreed that Jacobs and her children could live freely wherever they chose.

With the encouragement of friends and the editorial support of abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, Harriet Jacobs wrote her story of enslavement and escape to freedom. Her book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, was published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent. Her deeply personal, compelling narrative encouraged women of the north to become activists in the anti-slavery cause. To this day, it remains a foundational firsthand account of the cruelty of slavery and a powerful spiritual text.

Harriet Jacobs is central to bringing the true picture of slavery to the American conscience; she wrote: “Reader, it is not to awaken sympathy for myself that I am telling you truthfully what I suffered in slavery. I do it to kindle a flame of compassion in your hearts for my sisters who are still in bondage, suffering as I once suffered.

In addition to her writing, Jacobs worked in support of the abolition movement, first in Rochester, New York, where her brother John had joined the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society. There, she became friends with Isaac and Amy Post and other renowned reformers. In the 1860s, Jacobs and her daughter Louisa founded the Jacobs School in Alexandria, Virginia, where mother and daughter taught hundreds of freed people. They worked for relief organizations in Savannah, Washington, D.C. and Boston. In Washington and in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Jacobs and her daughter took in boarders to help support themselves.

Jacobs, struggling with illness and nursed by her daughter, died in 1897, in Washington, D.C. Louisa arranged for her burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she lies with her brother John and daughter Louisa beneath a simple marker inscribed with an epigraph taken from Paul’s epistle to the Romans (12:11-12): Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit serving the Lord.

– authored by Bundy H. Boit

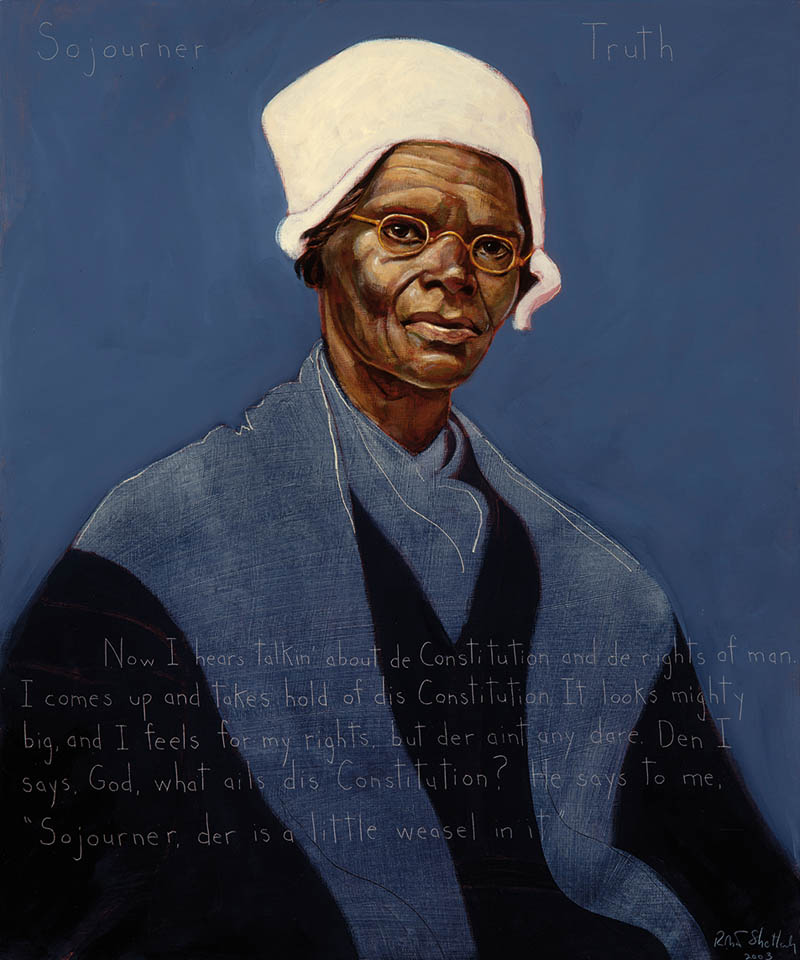

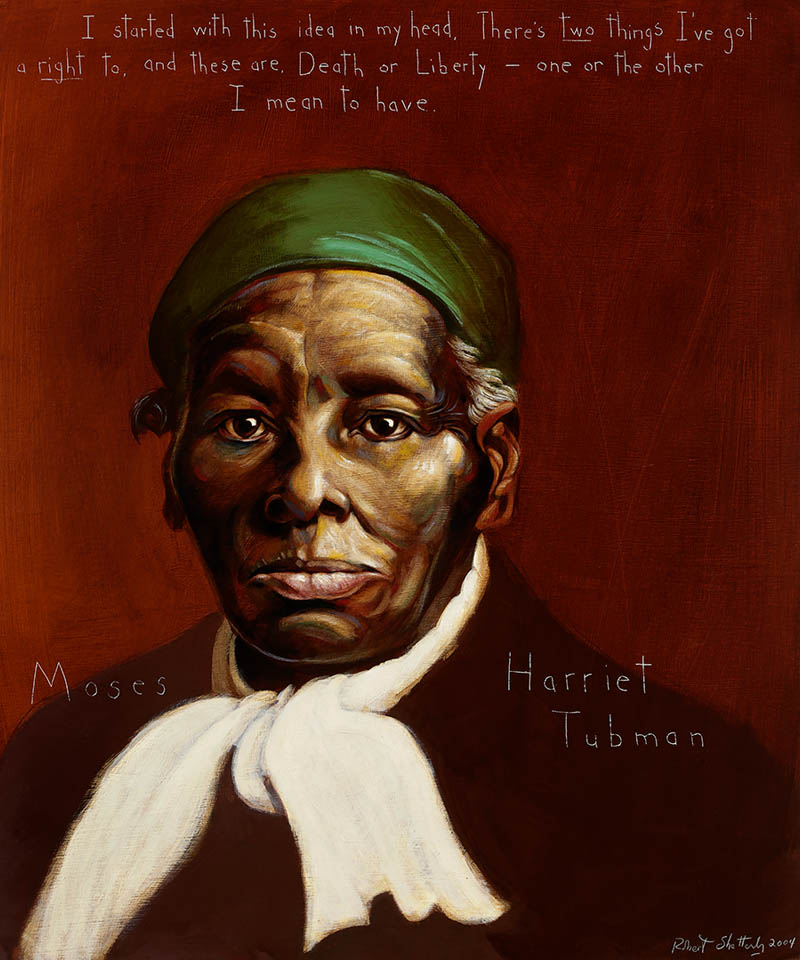

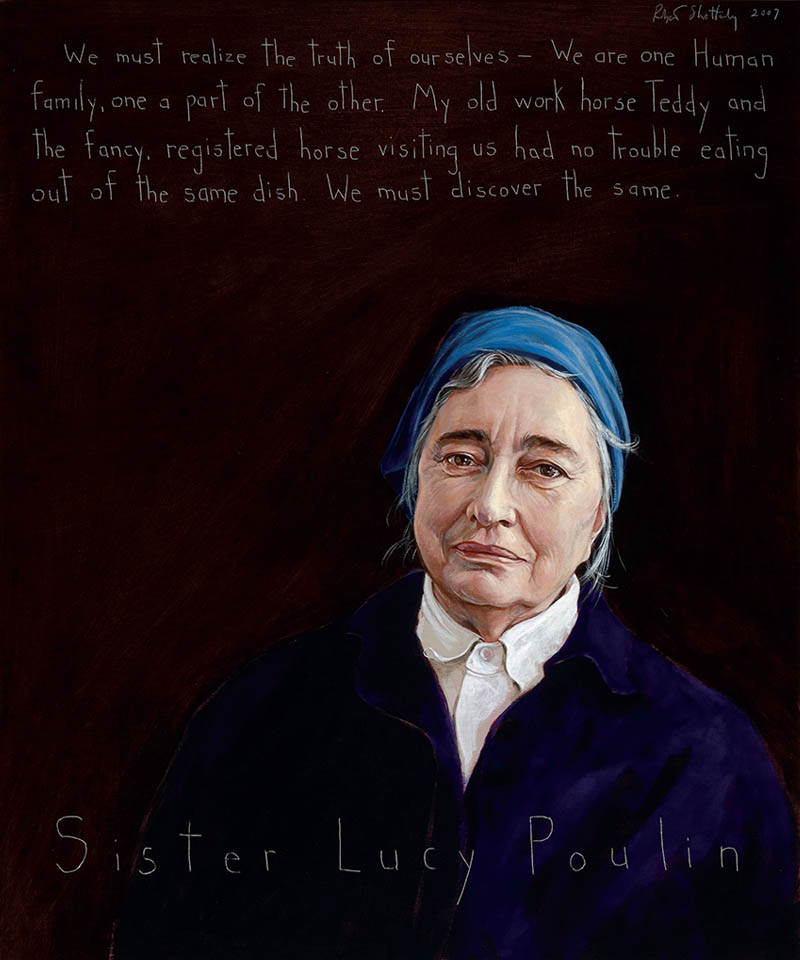

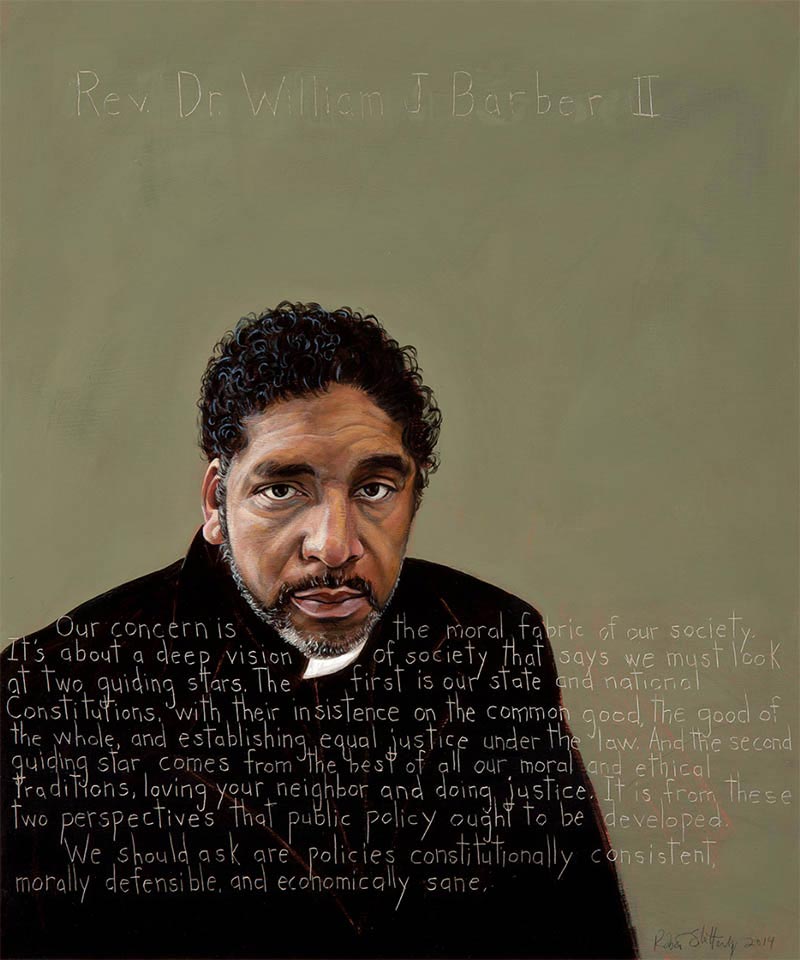

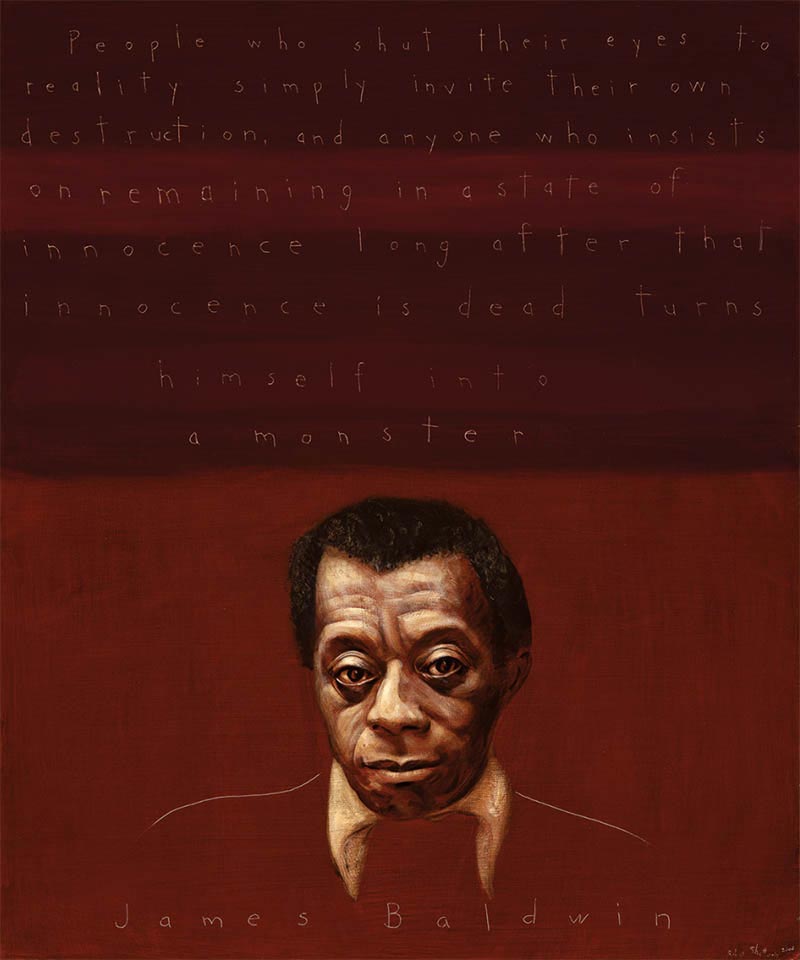

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.