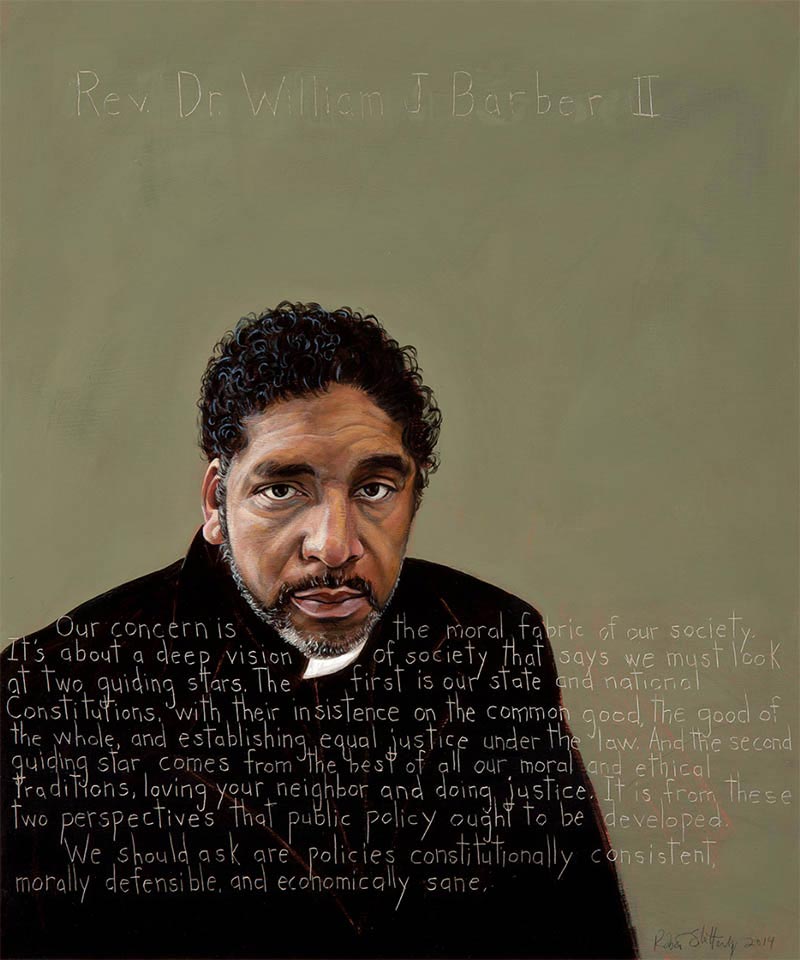

Dr. Rev. William Barber II

Minister, Organizer : b. 1963

“Our concern is the moral fabric of our society. It’s about a deep vision of society that says we must look at two guiding stars. The first is our state and national Constitutions, with their insistence on the common good, the good of the whole, and establishing equal justice under the law. And the second guiding star comes from the best of all our moral and ethical traditions, loving your neighbor and doing justice. It is from these two perspectives that public policy ought to be developed. We should ask are policies constitutionally consistent, morally defensible, and economically sane.”

Biography

“We have a new demographic emerging that is changing the South. The one thing they don’t want to see is us crossing over racial lines and class lines and gender lines and labor lines. When this coalition comes together, you’re going to see a New South.” The Reverend Doctor William J. Barber II offered this vision of the New South in a 2013 interview with the North Carolina based, independent newspaper Indy Week. The vision of the New South reflects his upbringing in a family committed to inclusive change.

Barber, born in Indianapolis, Indiana on August 30, 1963 (two days after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom), is the son of parents who, in the spirit of helping to build a “New South” in the twentieth century, moved from Indiana back to his father’s home of Washington County, North Carolina. Barber’s father served as the first African American teacher in the county’s white high school and his mother served as the same school’s first African American office manager. That change-agent spirit and desire to improve the broader community drives Barber’s activism. “I grew up under the tutelage of not understanding how to be a Christian without being concerned about justice and the larger community,” he says.

Barber graduated from Washington County’s Plymouth High School and matriculated at North Carolina Central University, a historically Black university in Durham. He earned a Master of Divinity degree from Duke University and a doctorate in Public Policy and Pastoral Care from Drew University. Barber married Rebecca McLean Barber and the couple has five children. For more than two decades, Barber has served as the pastor of the Greenleaf Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in Goldsboro, North Carolina. And in 2005, he was elected president of the North Carolina chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Through his work with the NAACP, Barber began focusing on his concern “about justice and the larger community.” As he worked to re-energize the chapter, he began to develop a political and social justice agenda that appealed not only to NAACP members but to progressive organizations throughout North Carolina. In 2006, Barber convened a meeting of several progressive advocacy groups in North Carolina, including organizations such as Equality North Carolina, the AFL-CIO and the North Carolina Council of Churches. That meeting led to the creation of the Historic Thousands on Jones Street People’s Assembly Coalition (HKonJ). In 2007, thousands of North Carolinians signed onto the HKonJ 14 Point People’s Agenda, which would include reform ideas such as raising the state minimum wage and linking future increases to inflation, ensuring health coverage for everyone, and expanding public financing of statewide elections. Some of these ideas were turned into bills and introduced to the state legislature.

As a student of political science and political history, Barber recognized the importance of building coalitions in order to make change happen. In the concept of “Fusion” politics – something that was particularly successful in post-Reconstruction-era North Carolina – Barber imagined a real vehicle for progressive ideas that could improve the lives of a majority of North Carolinians. In its nineteenth century form, Fusion politics in North Carolina represented the successful collaboration between members of the state’s Republicans and Populists, particularly in the elections of 1894, 1896 and 1898 when the racially diverse Fusion coalition successfully wrested control of the state from the divisive conservatives of the Democratic Party. Though ultimately defeated, that earlier movement inspired Barber to see a way to bridge racial, economic, religious and gender divides in the twenty-first century, particularly following the 2008 election of Barack Obama, who had won the state’s popular vote.

Barber recognized that Obama’s presidency had the potential of creating “a third Reconstruction.” (The first Reconstruction was from 1865-1877, followed by what historians have deemed the “second” Reconstruction – essentially the civil rights movement during the mid-twentieth century.) At the same time, however, Barber noted that the North Carolina conservatives’ “…attack on voting rights starts immediately after President Obama is elected,” in response to the threat of progressive change. Barber’s twenty-first century Fusion worked to stymie these aggressive tactics, while continuing to log legislative victories. Yet with the 2013 Republican takeover of the legislature and the governor’s mansion, the progressive political bulwark that the Fusionists helped build broke down and conservatives cleared the way to implementing an agenda to reverse many of the legislative victories in North Carolina that had expanded voting rights, ensured women’s reproductive rights and maintained proactive school integration policies.

The Fusion response to the regressive legislation that emerged from Raleigh would grow into the “Moral Mondays” movement, with the charismatic Barber at the helm.

“Every piece of legislation should pass this test. How does it benefit the good of the whole?” says Barber. On Monday, April 29, 2013, Barber organized a civil disobedience action at the North Carolina state legislature, calling on the participation of the organizations that he and the NAACP had organized into a progressive coalition over the prior six years. The next Monday, scores of marchers arrived to continue protesting the laws being passed through the state legislature. On February 8, 2014, thousands of protesters gathered at the “Mass Moral March” to show their support for the Moral Mondays movement and the principles it stands for. “Do not forget this is a movement, not a moment,” Barber reminded the marchers as it brought atheists, Jews, Muslims, Christians, gays, straights, Republicans, Democrats, rich, poor, white, Black, Latinos, Asians and others together to combat institutionalized privilege and racism. As a result of the attention garnered by North Carolina’s Moral Mondays movement, other states, particularly southern states, have developed or are developing their own Fusion movements in response to conservative legislation at the state level.

In 2017, Barber became co-leader of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. Barber notes that, “when they cut health care, that’s not a Black issue; that’s a people issue. When they cut unemployment [compensation] that hurts everybody.” Barber’s ability to simplify issues with his commanding moral authority and his astute recognition of an old and successful North Carolina political coalition to promote progressive ideas has the potential to show disparate progressive organizations throughout the United States a path to building coalitions around common goals. He often closes his speeches by having the crowd chant with him, “Forward together, not one step back!”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.