What's New

20th Anniversary of the Attack on Iraq

I’m surprised that after 20 years and no historical doubt that the Bush/Cheney administration lied to manufacture the political consent enabling the war on Iraq, our major media and the majority of our politicians refuse to call it what it was. Why is that? And what does it mean about what kind of country and democracy we are?

There are not simple answers to those questions, but I want to offer some conjectures which may help us understand who we are. Politicians and media spokespeople know that a democratic society cannot exist without the Rule of Law, law that is enforced equally across all strata of race and class and wealth like a steel thread woven into the tapestry of our republic. Those who call for the prosecution of Donald Trump for his many Illegal acts stress the importance of the equal distribution of the law. They are adamant that his wealth and privilege and status as a former president should offer him no protection. Since that is obviously true, what then should we do about George W. Bush and Dick Cheney who lied to start a preemptive war in 2003? They are guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. What power excludes them from the legal embrace of the law? War crimes are, I think, of a higher order of crime than anything perpetrated by Trump, and a more significant attack on democracy. What investment do so many politicians and news anchors have in shielding them?

Part of the answer to that last question is that most media and political power in this country failed to denounce the propaganda that produced the attack on Iraq. To call out Bush and Cheney now, they would have to call out themselves. And to call out themselves they would have to call out Barack Obama, too. Obama, upon taking office, implied that the Bush administration was guilty of crimes, but announced his policy of “looking forward rather than back.” A forward-looking policy disdains to mire itself in accountability for its predecessors. Accountability is messy. It’s divisive. It distracts from the future. It may show how many people have dirty feet and bloody hands. Of course, any rational person would say that the law has to look backward in order to look forward. But as messy, divisive, and distracting as accountability can be, it is absolutely essential to the integrity of democracy.

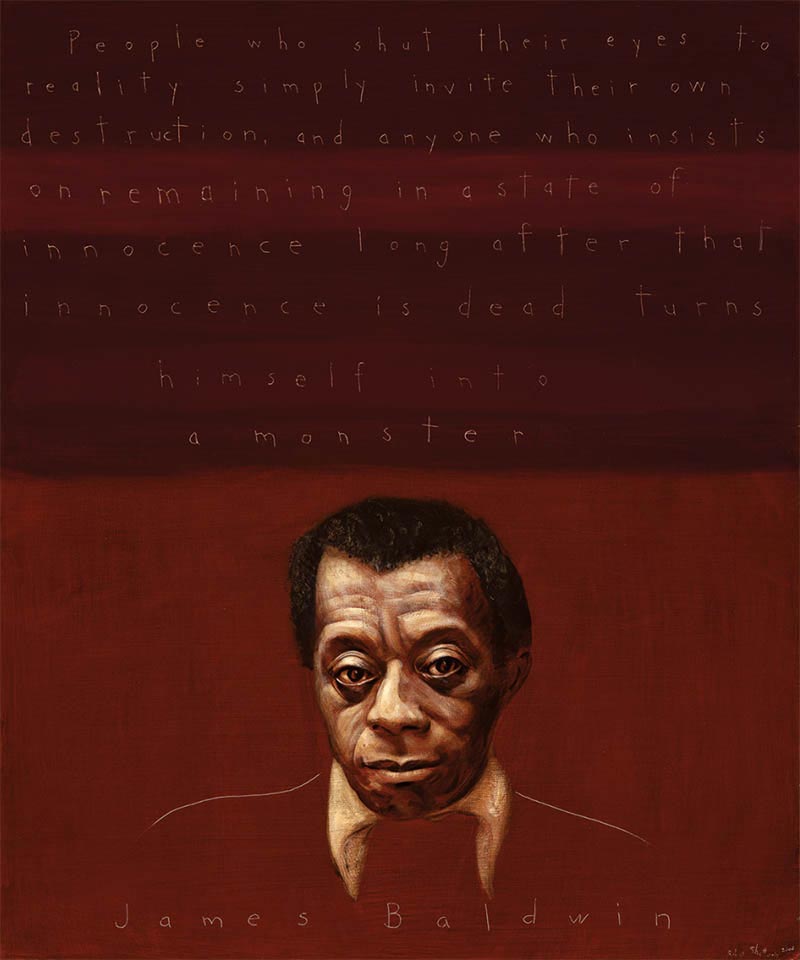

Accountability is what keeps us honest. It insists on knowing the truth. It helps protect us from the repetition of crimes. We can’t talk about the Rule of Law unless we are willing to struggle with accountability. We have no trouble demonizing the war criminals who have been our enemies – Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito, Stalin, now Putin. But we have more trouble naming and damning our own war criminals – Lyndon Johnson, Nixon, Reagan, the Bushes. Does that mean that it’s too uncomfortable for the ruling class to prosecute its own leaders as criminals? To do so certainly undermines the notion of U.S. exceptionality. How can exceptional people who live in the City on the Hill be monsters? (I’m thinking of James Baldwin saying, “… anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.”) When Americans commit war crimes, we call it the result of honest mistakes. Those crimes are like collateral damage – unfortunate but unavoidable for our virtuous national interests.

There have been loud calls to hold Putin and Russia responsible for paying reparations for their war crimes in Ukraine – rightly so. But if we tell the truth about the U.S. war on Iraq, we would have to pay to rebuild all the damaged infrastructure caused by our relentless bombing, pay reparations to the families of the millions of dead and displaced, for poisoning the environment, for the ongoing dire health effects of our toxic militarism.

Who wants to tell the truth when the truth is so expensive? Or, asked another way, how much is morality worth? How much is the Rule of Law worth when it exposes us as hypocrites? Better to cultivate forgetting than pay the moral or economic cost.

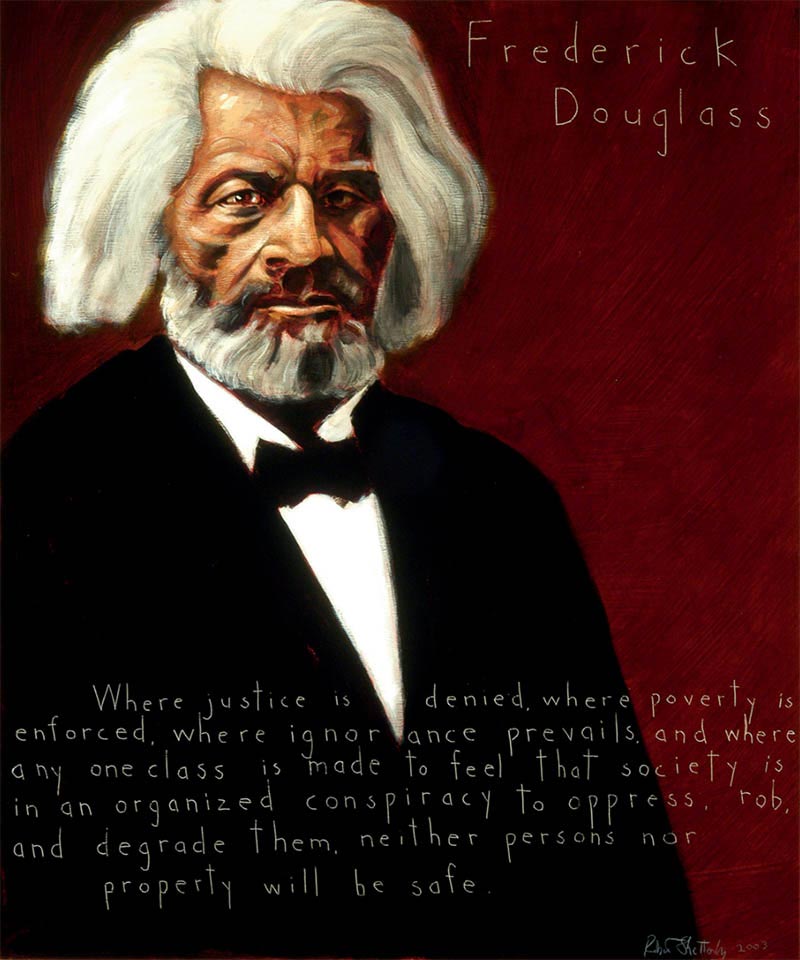

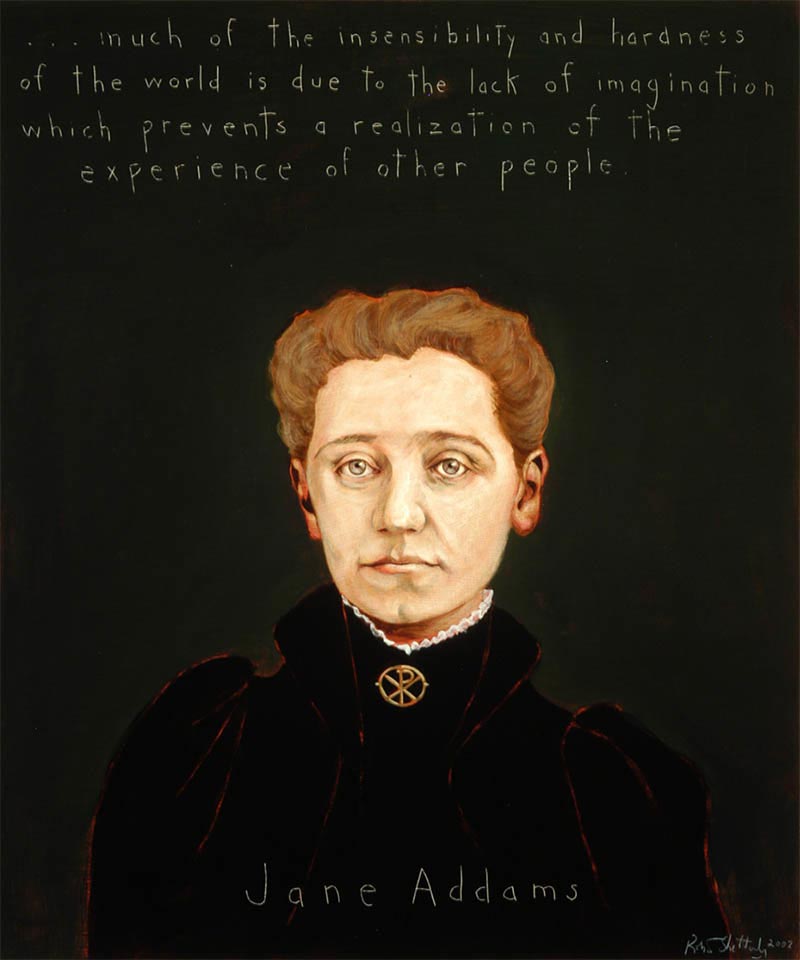

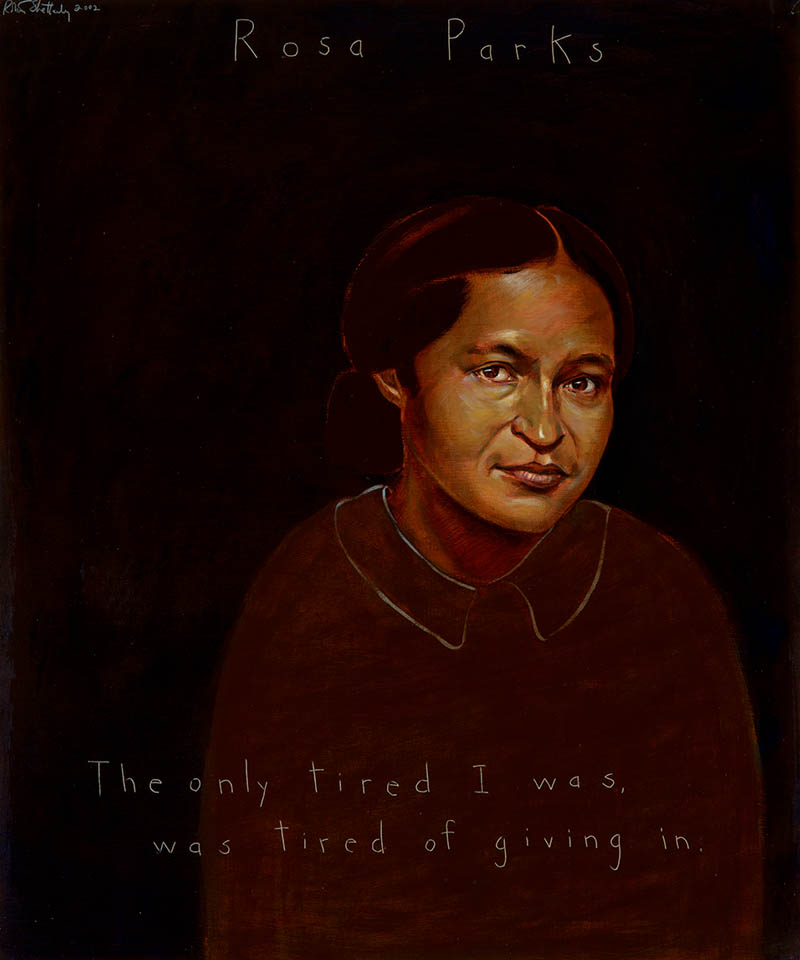

This project, Americans Who Tell the Truth, began with my discomfort in being made complicit as an American citizen in the crime of attacking Iraq. Joining protests and writing letters failed to interrupt the rush to war, nor could they blunt my anger, guilt and grief. I had to engage more deeply, make a moral commitment deeper than simply sigh at the unpleasant news cycle and worry over the bump in the price of oil. When powerful people in government, the courts and the media, who are entrusted with defending the Rule of Law, flaunt it, what are we to do? Some people assess such atrocious crimes and say, I hate this country! For me to say that would deepen my sense of alienation. I don’t hate the ideals of this country. I hate their betrayal. I don’t hate the people of this country. To say that would mean that I hate Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, hate Eugene Debs and Mother Jones, hate Bob Moses and Ella Baker, hate Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold, hate Daniel Ellsberg and Jane Addams. By loving these people and the other 250 whom I’ve painted, loving them by trying to live up to their example of courage and their insistence on truth telling, is the only way I know how to feel at home here.

When our country turns out to be a righteous and murderous bully, so powerful that no other country can hold it accountable, and its own legal structure fails to do so, its citizens must witness the truth. We must refuse the helpless cynicism of another horror war being committed in our name. That cynicism says that this is about us, but we can’t do anything. It isn’t about us. It’s about the victims of our policies. If we ignore our responsibility to them, we have become perfectly complicit in a bankrupt government.

When I speak – to any audience or classroom – I talk about the origin story of this project. It’s a combination of moral and historical compulsion insisting to me that the full story be told. It feels to me a betrayal of the victims not to tell it. And a betrayal of the hope that the perpetrators can still perform some form of redemption. When unjust power commits crimes, it prefers to pull a blanket of oblivion over the past. Most citizens prefer to snuggle under that blanket, too. The acknowledged truth disquietingly nags at one to take responsibility.

But for most young people it already is ancient history. In 1955, when I was 9 years old, the year Rosa Parks kept her bus seat in Montgomery, only ten years after the end of WW II, that war – our good war – seemed like ancient history. Mighty Mouse cartoons and Howdy Doody seemed more real. Our cities, unlike Germany’s or England’s, were not still reminding us with their mountains of rubble. Having expended so much energy in bearing witness to the atrocity of the Iraq War, it remains ever present for me like a hornet buzzing in a bottle from which it will never escape until its story is told, its crimes held to account.