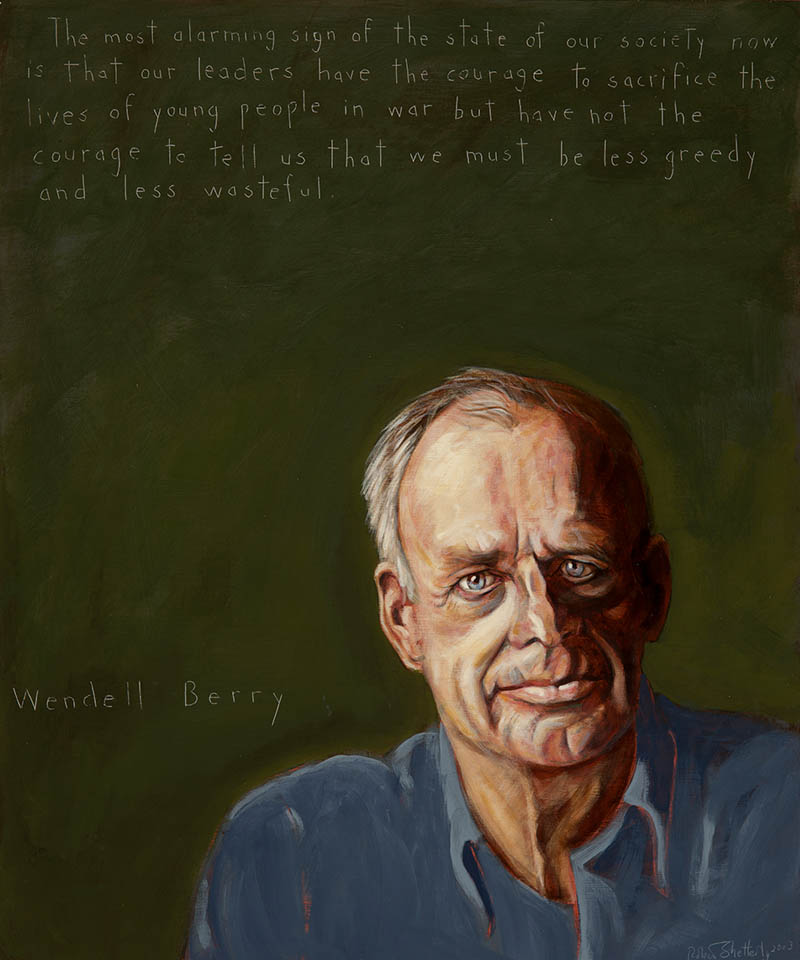

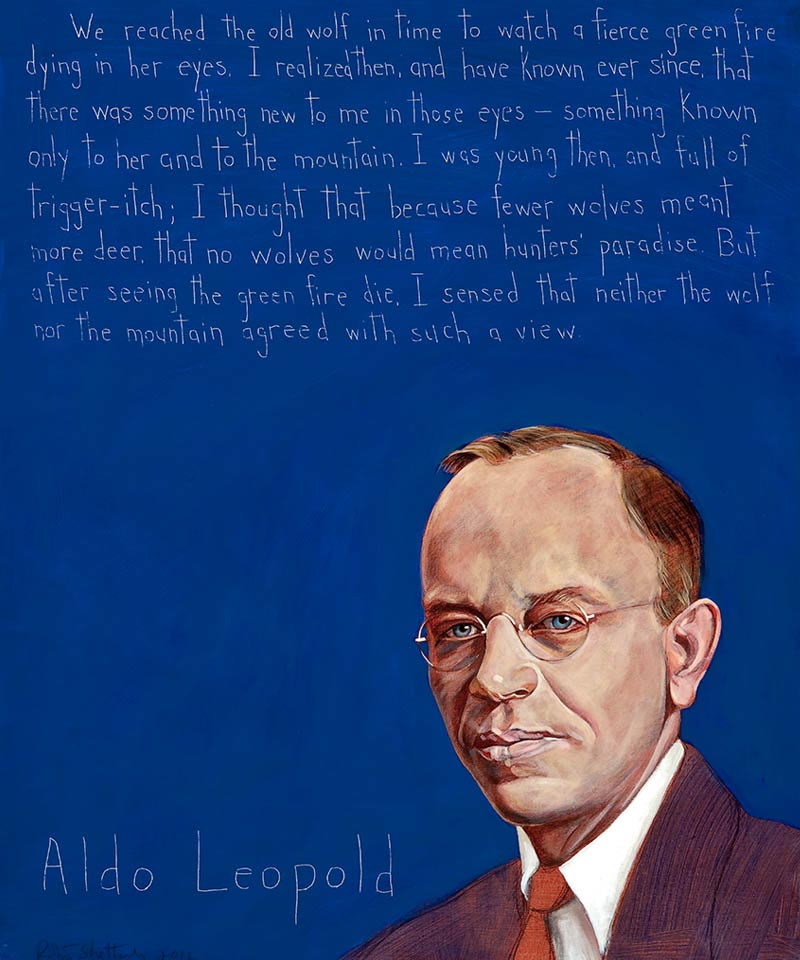

Aldo Leopold

Scientist, Environmental Ethicist, Professor : 1887 - 1948

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and I have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.”

Biography

As people today are becoming increasingly aware, the eradication of any species, be it flora or fauna, carries with it serious consequences for local and global ecosystems. Aldo Leopold saw the dangers of putting people’s needs and wants ahead of the planet’s health well before the modern environmental movement, and helped shape today’s efforts to preserve what wilderness we have left.

Aldo Leopold spent his childhood in Iowa exploring the woods with his siblings and father, learning about all different kinds of wildlife, and observing and cataloguing the different species he saw. He loved the outdoors, and carried this love with him, and eventually, he went to Yale to earn a graduate degree from the university’s recently established Forest School.

After graduating in 1909, Leopold joined the Forest Service in the Southwest. He worked on plans for managing the Grand Canyon and for establishing the first official wilderness area in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest. He also wrote the first game and fish handbook for the Forest Service.

Leopold’s initial objective was to control certain predators in order to help farmers and ranchers in their work and protect the people who visited national parks. Hunting animals such as bears and wolves was the accepted method of maintaining wildlife refuges and recreational parks, and was considered good wildlife management.

However, Leopold began to see the wilderness in a very different light. He came to believe that that preserving one species over another, for whatever reason, was doing more harm than good. He observed technology (automobiles, machinery, etc.) creeping into the national parks and wild areas, and began to think that human dominance over the earth was the wrong way to treat the planet.

Leopold began to write about creating a new “land ethic”—where human beings are participants in the “land community,” with a duty not to exterminate species but to work for their benefit. He wrote, “The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land. . . . A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these ‘resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state.”

This natural state finds balance without the interference of mankind. He expresses this opinion in his piece “Thinking Like a Mountain,” where he observed the effects of killing wolves to create a herd of deer:

I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

Since then I have lived to see state after state extirpate its wolves. I have watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer trails. I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anaemic desuetude, and then to death. I have seen every edible tree defoliated to the height of a saddlehorn. Such a mountain looks as if someone had given God a new pruning shears, and forbidden Him all other exercise. In the end the starved bones of the hoped-for deer herd, dead of its own too-much, bleach with the bones of the dead sage, or molder under the high-lined junipers.

I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades. So also with cows. The cowman who cleans his range of wolves does not realize that he is taking over the wolf’s job of trimming the herd to fit the range. He has not learned to think like a mountain. Hence we have dustbowls, and rivers washing the future into the sea.

In 1935, Leopold and some colleagues formed an organization called the Wilderness Society, dedicated to preserving wilderness. They wanted to save “that extremely minor fraction of outdoor America which yet remains free from mechanical sights and sounds and smells.” Almost a century later, the Wilderness Society continues to thrive, having “led the effort to permanently protect 109 million acres of wilderness in 44 states.”

In the same year, Leopold bought a run-down farm in Wisconsin. He and his family lived in a chicken coop they renovated and called it “the Shack.” They spent countless weekends there planting trees and working the land to bring it back to a semblance of its natural self. Leopold wrote down his observations of this land and his work on it. He developed his idea about the land ethic. The resulting book of essays, A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There, was published the year after his death in 1949. The book continues to influence conservation and ecology, alongside Thoreau´s Walden and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Leopold’s ideas provided the foundation for the study of wildlife ecology and a sense of our place in the planet’s ecosystem.

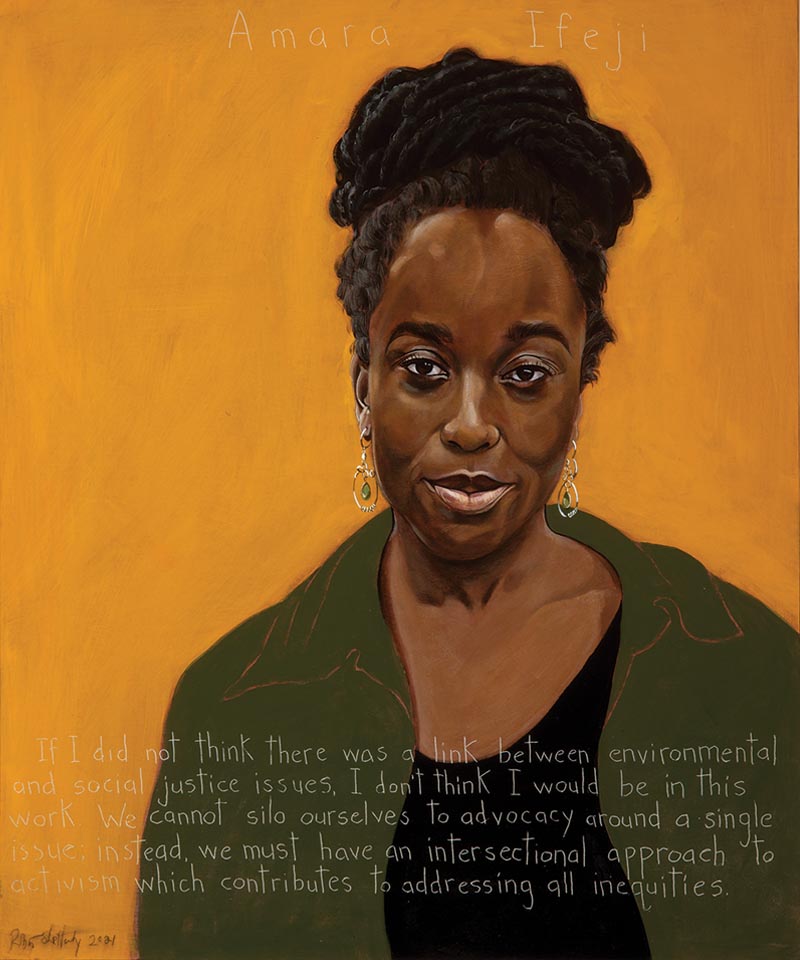

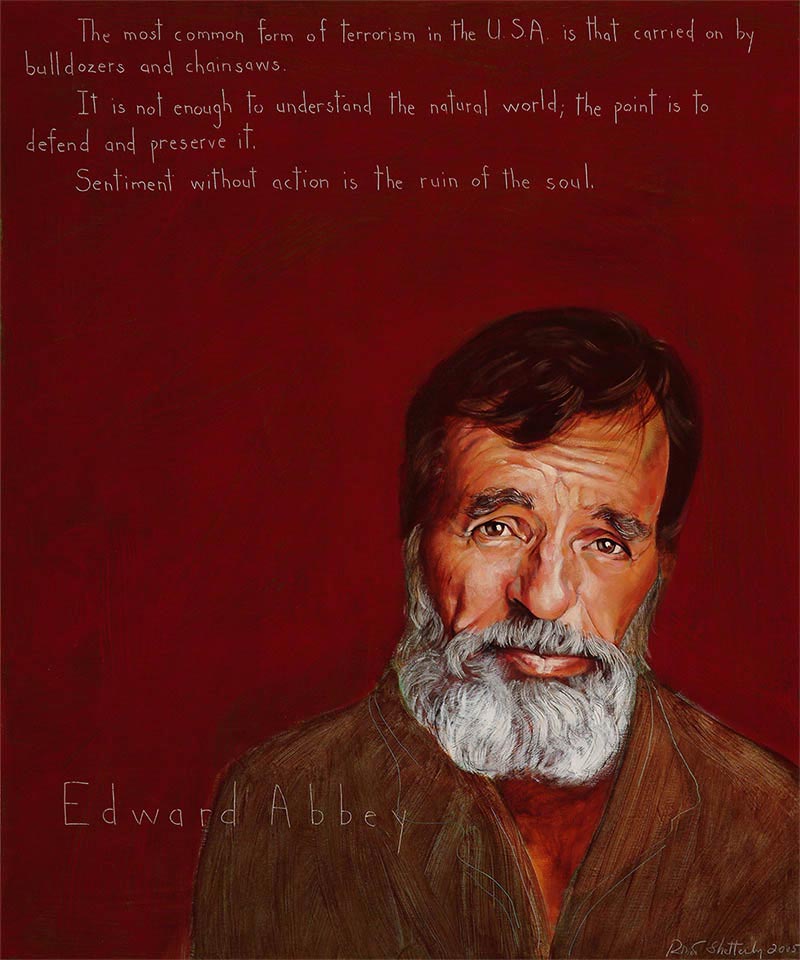

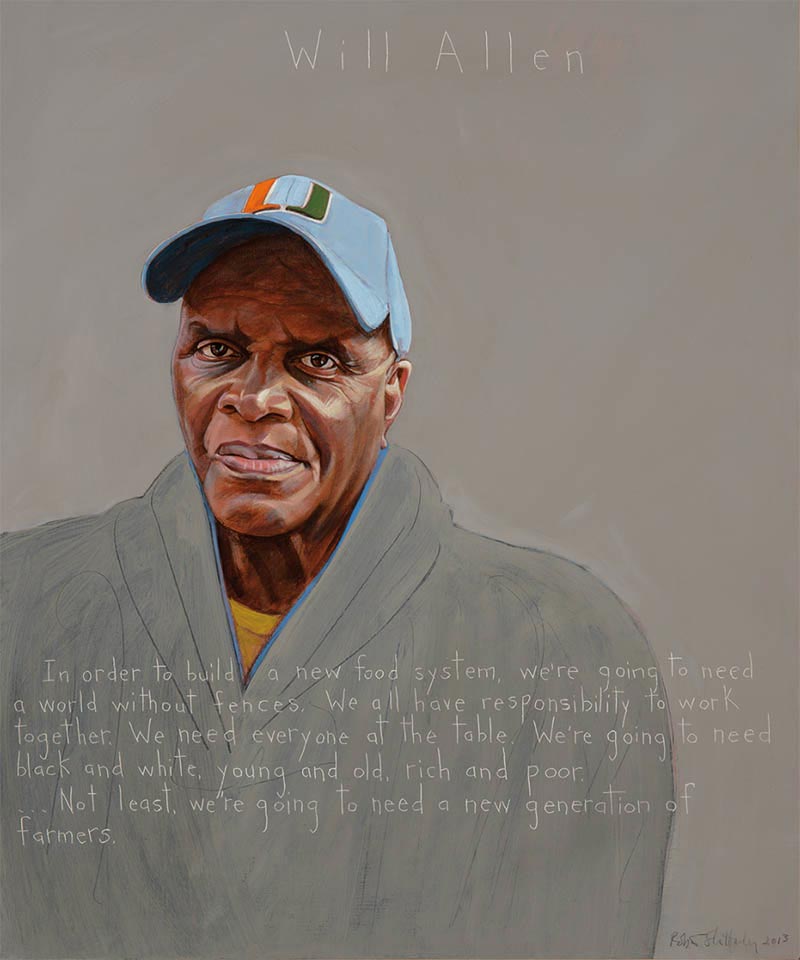

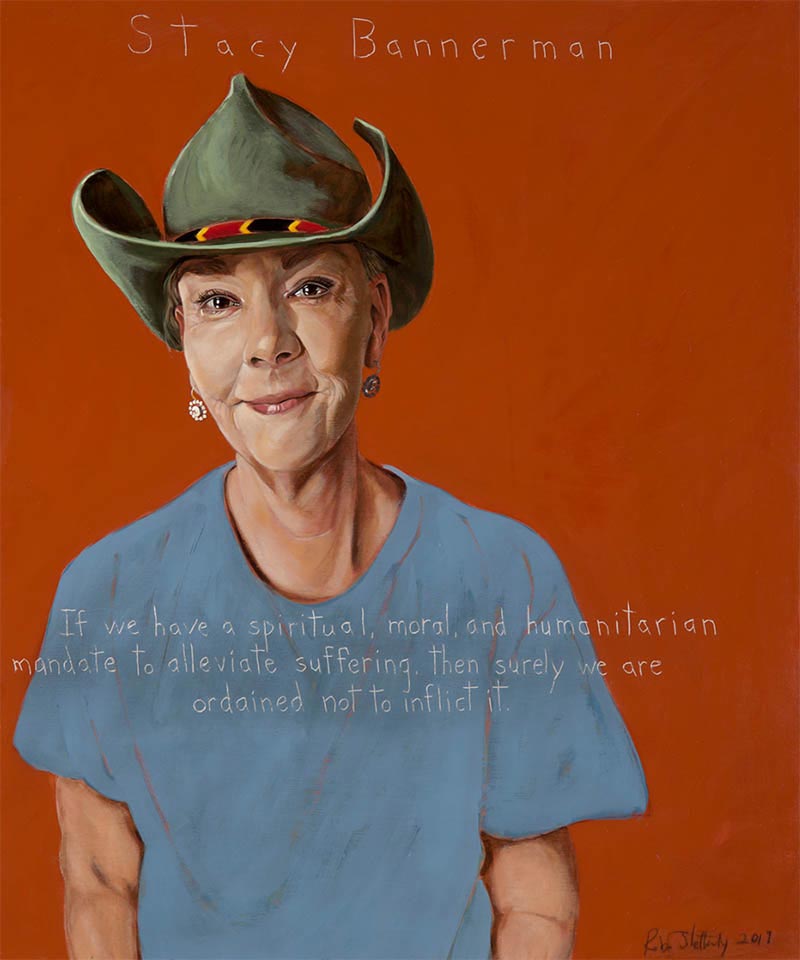

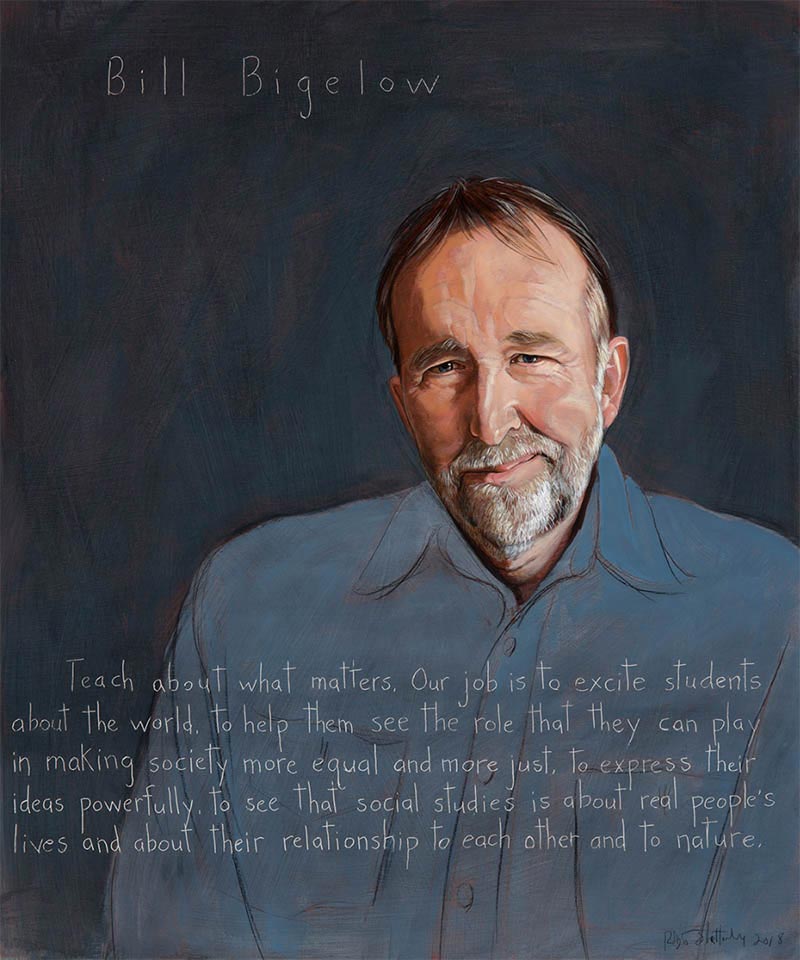

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.