Stacey Abrams

Civil Rights and Voting Rights Activist; Legislator : 1973

“… citizenship requires constant action, which includes voting, protesting and participating: and without the combination, we are all in jeopardy.”

Biography

Graduate of Spelman College, University of Texas Lyndon Baines Johnson School of Public Affairs, and Yale Law School

Atlanta Deputy City Attorney (2002)

Member of the Georgia House of Representatives (2006)

Georgia House Minority Leader (2010)

Candidate for Georgia Governor (2018)

Founder and leader of the voting rights organization Fair Fight Action

Author of Lead from the Outside, Our Time is Now, While Justice Sleeps, and eight romantic suspense novels under the pen name Selena Montgomery.

Member of the Council on Foreign Relations, Next Generation Fellow of the American Assembly on U.S. Global Policy and the Future of International Institutions, and member of the World War Zero bipartisan coalition on climate change.

Board member of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, the Marguerite Casey Foundation, the Center for American Progress, and the Women’s National Basketball Players Association.

Throughout U.S. history, there have long been strong advocates for expanding access to voting rights, with those advocates recognizing how the nation would change with new voices having a say in how they’re governed. These changes happened with the elimination of property requirements to access the ballot. They happened again with universal white male suffrage, and again when the formerly enslaved men gained the right to vote with the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870. With the franchise extended to women through the 19th Amendment in 1920, the nation changed once again. However, it wasn’t until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that the U.S. guaranteed all of her citizens the right to vote, regardless of race or gender, and to have that right thoroughly defended. Yet, even with the passage of the Voting Rights Act, strong advocates pushed further until young people, beginning at the age of 18, were granted the right to vote with the ratification of the 26th Amendment in 1971.

While those strong advocates who fought to expand the franchise did in fact help to change the nation, there was also the struggle of African Americans to realize fully their right to the franchise that truly moved the nation forward. Indeed, there is a throughline in the narrative of African American history that showcases how other formerly disenfranchised citizens were able to take advantage of the gains made through African American advances, and then advance the nation as a whole.

Stacey Yvonne Abrams has joined the ranks of those strong historical advocates fighting to ensure that voting rights are accessible to all who are eligible to exercise them. Born December 9, 1973, in Madison, Wisconsin, Abrams came of age during the post-Civil Rights era and in a period when the U.S. continued to uphold the principles of the Voting Rights Act. The key was to push for expanded registration among the electorate so that as many people who had the right to vote guaranteed would exercise those rights.

Abrams, whose parents Robert and Carolyn Abrams are Methodist ministers, was raised primarily in Gulfport, Mississippi, though her family eventually would move to DeKalb County, Georgia, just outside of Atlanta. Her parents were participants in the Civil Rights Movement, and Abrams is a member of the first generation of Americans to grow up during a time without slavery and without legal segregation. However, Abrams recalls her time in Mississippi, remembering that “… the Confederate battle emblem was the entirety of the state flag,” and noting that her teachers “taught from books that failed to rebuke the traitors who tried to overthrow the government to retain their right to own my ancestors.” With those Civil Rights era battles still well within living memory, Abrams parents imbued all six of their children with the understanding that those struggles of the past continued and that the defense of those gains would remain important.

In preparation for her future role as a strong advocate for the franchise, Abrams, the first Black valedictorian of Decatur, Georgia’s Avondale High School, earned a Bachelor’s degree at Spelman College in Atlanta, a Master’s degree from the Lyndon Baines Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, and a Juris Doctor from Yale University’s School of Law. Following her graduation from Yale, Abrams returned to Atlanta to go into private practice and was tapped to serve as a Deputy City Attorney for Atlanta in 2002. In 2006, she was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives for the 84th, and subsequently the 89th, district (primarily DeKalb County). Abrams rose through the ranks to become the House Minority Leader in 2010, a first for an African American woman in the state. From her positions, Abrams was able to recognize that “we are a better country when we defend the weakest among us and then empower them to choose their own futures.” Not only was Abrams able to try to defend the weak and seek to empower Georgians to have those self-determined future choices, but she also experienced, from her position within Georgia’s government, how “the codification of racism and disenfranchisement is a feature of our lawmaking — not an oversight.” It was during Abrams tenure in the Georgia legislature when the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of Shelby County v. Holder (2013), invalidated section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That section of the law required jurisdictions with a history of race-based attacks on the franchise to submit all legislative changes of their voting laws to the Department of Justice for review. The Court found section 5 to be unconstitutional, and within hours of that ruling states began putting forth changes to voting rules. Abrams didn’t miss a beat, founding the New Georgia Project the same year as the Supreme Court ruling with the goal of registering tens of thousands of unregistered Georgia voters in time for the midterm elections of 2014.

Most states throughout the South began changing aspects of their voting laws following the Shelby County decision. Many settled on voter identification legislation, without the guarantee of free access to purchase said identification, as well as voter purges, with the end goal of suppressing the number of eligible voters. As Abrams noted, the “contours and tactics of voter suppression have changed since the days of Jim Crow, Black Codes or suffragettes, but the mission remains steady and immovable: keep power concentrated in the hands of the few by disenfranchising the votes of the undesirable.” And in most instances, “the undesirable” happened to vote primarily for Democratic candidates.

Following her departure from the Georgia House of Representatives, Abrams decided to run for Governor of Georgia. In securing the Democratic nomination, she became the first African American woman in the nation to gain a major party’s nomination in a gubernatorial race. Abrams’ opponent in the race, Brian Kemp, was the sitting Secretary of State and had a track record for using voter suppression tactics in that position, including in their 2018 race. Abrams lost to Kemp by less than 60,000 votes. Though she acknowledged Kemp’s win, Abrams did not offer a formal concession, something she was criticized for not doing. Even though she was clear in her belief that Kemp used voter suppression to obtain his victory, she followed the various procedures to make sure of the accuracy of the count and only then acknowledged his win. In so doing, in answering her critics, she noted that “I have always ever fought to make certain that every vote got counted, and every person got included.” That is the opposite action of those who seek to suppress voters.

In the wake of her loss in 2018, Abrams founded the organization Fair Fight Action with the goal of battling voter suppression, and bolstering the ongoing work of the New Georgia Project in mobilizing voters. Abrams understands that the demographic evolution of the nation will create political changes that many will find discomfiting. But, as Abrams recently said in an interview on the PBS NewsHour, “… if the response to increased participation by communities of color, by young people, by women … if the response is to restrict their access and impede their participation … that is a very, very strong signal that we are heading in the wrong direction, and that our democracy is not safe, it is not sound, and it is not resilient. We have to be better than that.” That clearly is a sentiment that Abrams’ historical predecessors would have understood during their efforts to expand the franchise and to ensure that all who were able to participate would have their voices heard.

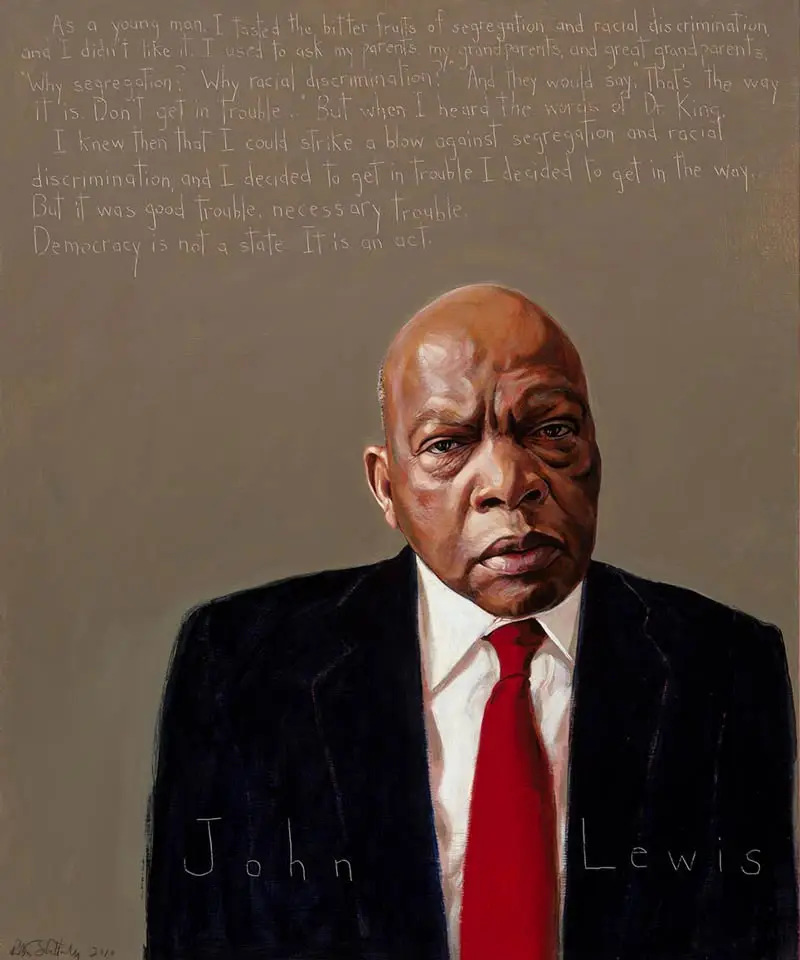

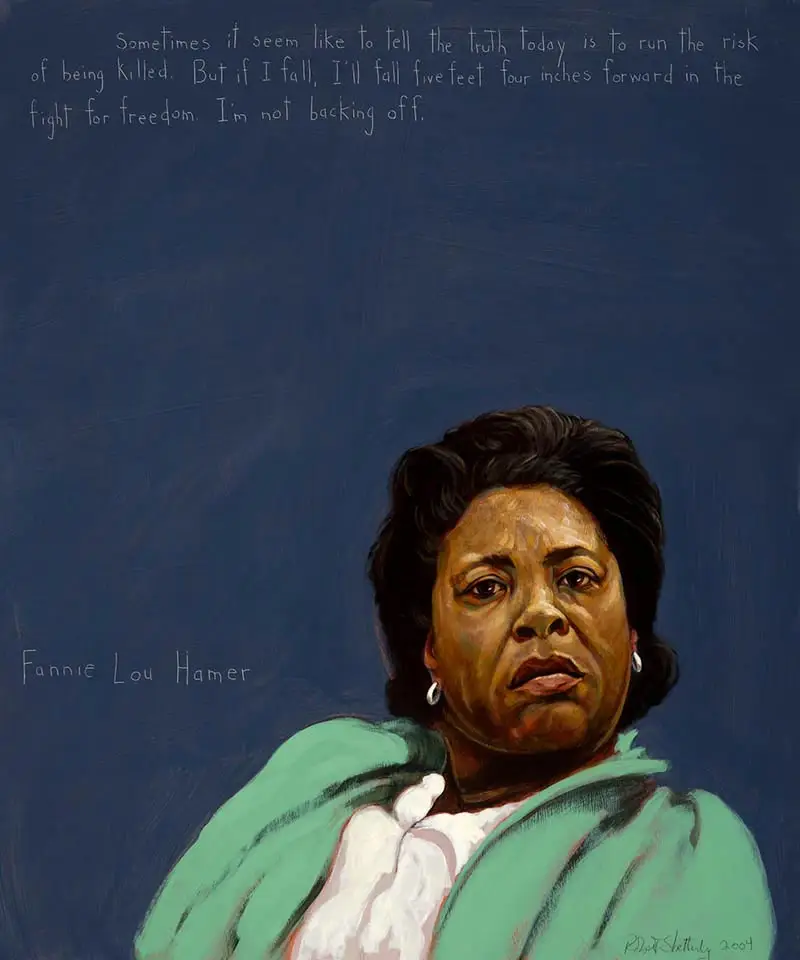

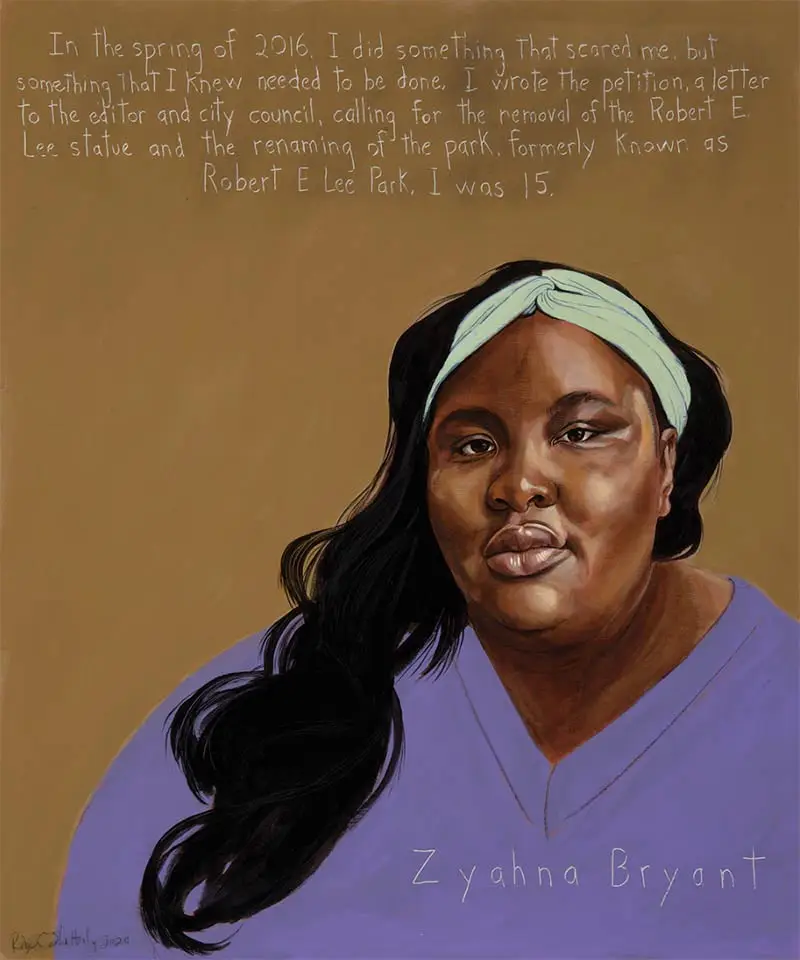

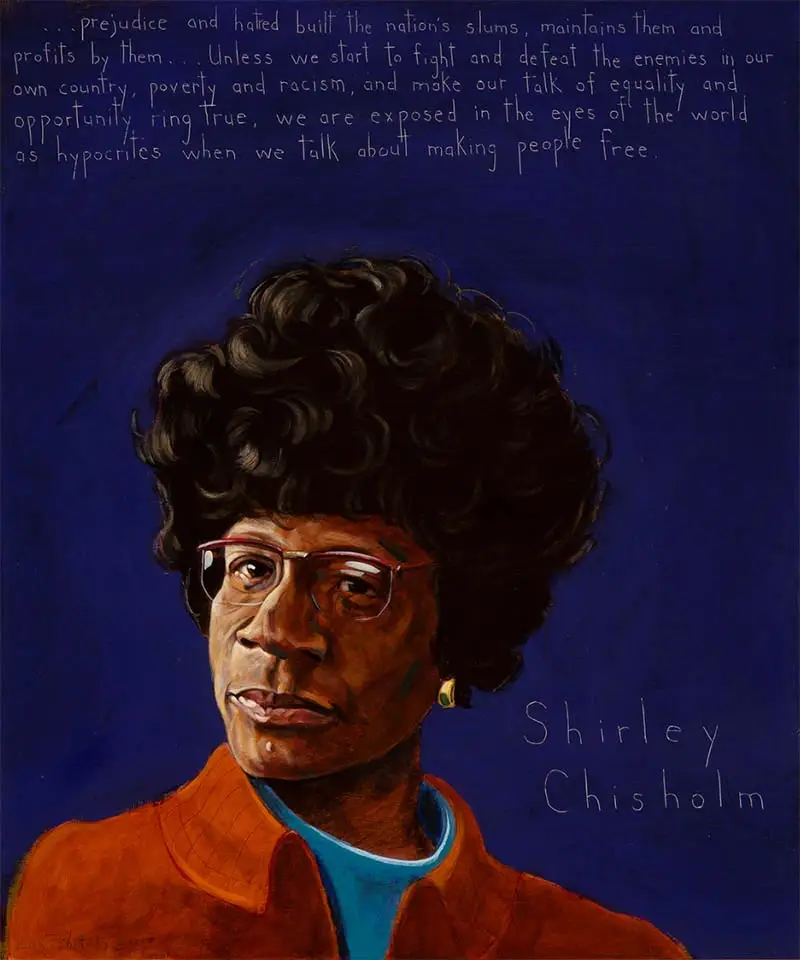

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.