Dr. Bernard Lown

Dr. Bernard Lown

Medical Pioneer, Peace Activist, Humanitarian; b. 1921, d. 2021

“Securing a future free of genocidal weapons requires above all eliminating the political and economic inequities that sunder rich and poor countries. As the Berlin Wall divided East and West, so inequality now creates a fracturing divide that augurs global chaos, terrorism, and war.”

Biography

- graduated summa cum laude from the University of Maine with a B.S in zoology

- earned medical degree at Johns Hopkins Medical School

- instituted radical changes in coronary care practices, including pioneering new drug protocols, developing the Direct Current Defibrillator, illuminating the role of psychological stress factors on cardiovascular health, and helping to establish one of the first coronary care units

- founded a cardiovascular clinic, a cardiovascular research foundation, and the Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank advocating for a just and caring health system

- formed Physicians for Social Responsibility

- with Soviet cardiologist Evgeny Chazov, formed the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War; the two men accepted the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of that organization.

- Bernard Lown Peace Bridge dedicated to Lown in his home town of Lewiston, Maine, in October 1988.

As a renowned cardiologist, inventor, teacher, peace activist and humanitarian, Dr. Bernard Lown acted with moral urgency to remedy the world’s injustices. From pioneering advancements in the treatment of cardiovascular disease to becoming one of the world’s most influential nuclear disarmament activists, Lown was committed to “behaving as though the destiny of our world depends on each of our actions. This is the moral imperative of our age.”

In 1935, at the age of fourteen, Lown emigrated with his parents from Lithuania to the United States to avoid Nazi persecution. They settled in Lewiston, Maine, where his father found work with relatives who owned a shoe factory. In 1937, Lown went to work in the factory to fill in for workers who had joined the Lewiston-Auburn Shoe Strike. He witnessed the harsh beating of a striker who had verbally taunted a strike-breaker. He was outraged at the sight of policemen arresting the unconscious, bleeding striker, while allowing his strike-breaking assailant to walk free. Lown jeopardized his relationship with his family and joined the striking workers.

Lown came to understand that the justice system was biased against the striking workers, denying them of their civil rights. The striking French Canadian workers were accused of being part of an international communist conspiracy. “No doubt,” said Lown, “the fact that I was a recent refugee from Hitlerism accounted for the deep impact those events had on me. . . . I have retained a permanent sense of outrage against such unfairness and injustice ever since. . . .” Lown had found his mantra: Question everything; accept nothing.

During high school, Lown experienced discrimination first hand. Yet to master English, he was mocked by fellow students and derided by his English teacher as “a bumbling idiot.” He gained admittance to the University of Maine on a trial basis. The dean commented that if he worked hard he was a potential “C” student. Lown graduated summa cum laude with a B.S in zoology.

In Lewiston, Dr. Max Hirshler, a German immigrant, befriended Lown. As a guest in Hirshler’s home, he observed that the discourse was not about medicine, but music and poetry. “I concluded . . . that doctors were in the cultural avant-garde of civilization. From that moment on, I was determined to pursue medicine.” Lown entered Johns Hopkins University School of School in Baltimore.

As a student at Hopkins, Lown risked his own future in medicine rather than allow inequities to go unchallenged. He rebelled against the segregation of blood in the hospital’s blood bank. His brave defiance of that racist policy resulted in his temporary expulsion from the school but saved countless lives.

Lown accepted a fellowship at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital) in Boston. He ascended the ranks of medicine and academia to become a professor of cardiology at the Harvard School of Public Health and a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

His constant review of standard procedures led to radical changes in coronary care practices, including pioneering new drug protocols, developing the Direct Current Defibrillator, illuminating the role of psychological stress factors on cardiovascular health, and helping to establish one of the first coronary care units. He founded a cardiovascular clinic, a cardiovascular research foundation, and the Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank advocating for a just and caring health system. Often met with skepticism, Lown’s innovations are heralded as major medical breakthroughs.

Lown criticized the U.S. healthcare system for failing to address the inequalities in race and economics. He said, “The most common cause of disease in the world is poverty. So how can you be a doctor and be indifferent to poverty?” About politicians he said, “With few exceptions, they rise to the challenge only when a mobilized public . . . clamors for change and forces them to do so.”

Lown impressed upon his fellows that they must listen to their patients, touch them and learn from them. He implored: “The patient is not a heart, a liver, or a nerve pain. . . . You can’t take care of a patient until you are part of the fabric of that person’s life.”

In 1961, Lown attended a lecture by Philip Noel-Baker, a British diplomat who had won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in multilateral nuclear disarmament. Lown was deeply alarmed by Noel-Baker’s prophecy that there wouldn’t be a world in the year 2000 because “the nuclear arms race is like a house of matches and it’s going to topple, and when it does, human life will end.” He recalled, “I left in a state of shock. I was working on sudden cardiac arrest, but the threat to humankind was sudden nuclear death. I had to do something.”

He formed Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), a group of Boston area colleagues, to study the consequences of a nuclear attack. They recognized that they would have nothing to offer, not even a token benefit, in the aftermath of an attack. “PSR hoped to consign the possession of nuclear weapons, like cannibalism, to the historical junk heap of inhumane aberrations. We hammered away at a medical truth: when a problem [nuclear war] lacks a cure, prevention must be the exclusive strategy.”

As the Cold War waged on, Lown came to believe that the U.S. military-industrial agenda was focused on the survival of weapons rather than on the survival of human beings. He was alarmed that the Western establishment and its mass media exaggerated Soviet misdeeds in order to buttress support for the nuclear arms race. He asserted that, “The Cold War was sustained by the fear of a treacherous Soviet enemy preparing to destroy us. . . . In an unstable climate of terror, feeling besieged by a foe without scruple leads to a state of jumbled intellectual incoherence, blocking the only exit: meaningful dialogue between adversaries.”

Essential to the creation of dialogue was the friendship between two of the most esteemed cardiologists in the world: Yevgeni Chazov of the Soviet Union and Bernard Lown. They had been collaborators in research. Lown recalls, “Chazov and I had become friends. I told him that as doctors we share a goal to heal and we must show humanity that we must learn to live together or we will die together. There is no other option.” Their friendship laid the groundwork for cooperation and enabled the formation of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW).

They agreed that physicians have no right to stay silent when the preservation of life and health of hundreds of millions is at stake. Physicians from eleven countries participated in the first IPPNW international congress. By the fifth congress in 1985, the organization had 135,000 activists in forty countries supporting nuclear disarmament. In 2024, IPPNW represents sixty-four countries and remains a leader in the global movement for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

In December of 1985, Lown and Chazov accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of IPPNW, for “creating awareness of the catastrophic consequences of nuclear war.” Instead of being praised in the U.S., Lown was demonized and accused of being a Communist sympathizer. “People told me that I was being duped by the KGB for opening dialogue with Communist colleagues.” The U.S. Senate passed a resolution asking the Nobel Committee to rescind the honor. Fortunately, it did not succeed. “One must communicate with an enemy,” Lown said.

In October 1988, the bridge that connects the towns of Lewiston and Auburn, Maine, was dedicated as the Bernard Lown Peace Bridge – the very same bridge where violent confrontation of the Lewiston-Auburn Shoe Strike took place. Lown said, “. . . the naming of a bridge is emblematic of my life,” Lown said. “My aim was always to connect. To connect the doctor with the patient, . . . a Soviet with an American, the rich world with the poor world. . . . We must be able to bequeath to our children the most fundamental of all rights . . . the right to survival.”

Lown remained an activist for disarmament and social justice for the rest of his life. He said, “I have learned that there can be no healthy United States in a sick world, no secure United States in a war-torn world, no affluent United States in a poor world. I am persuaded that we will not have a livable world unless we make it a more just world. To care for a person as a patient you must care for the survival of humankind.”

-authored by Lynn Gonzalez

Resources

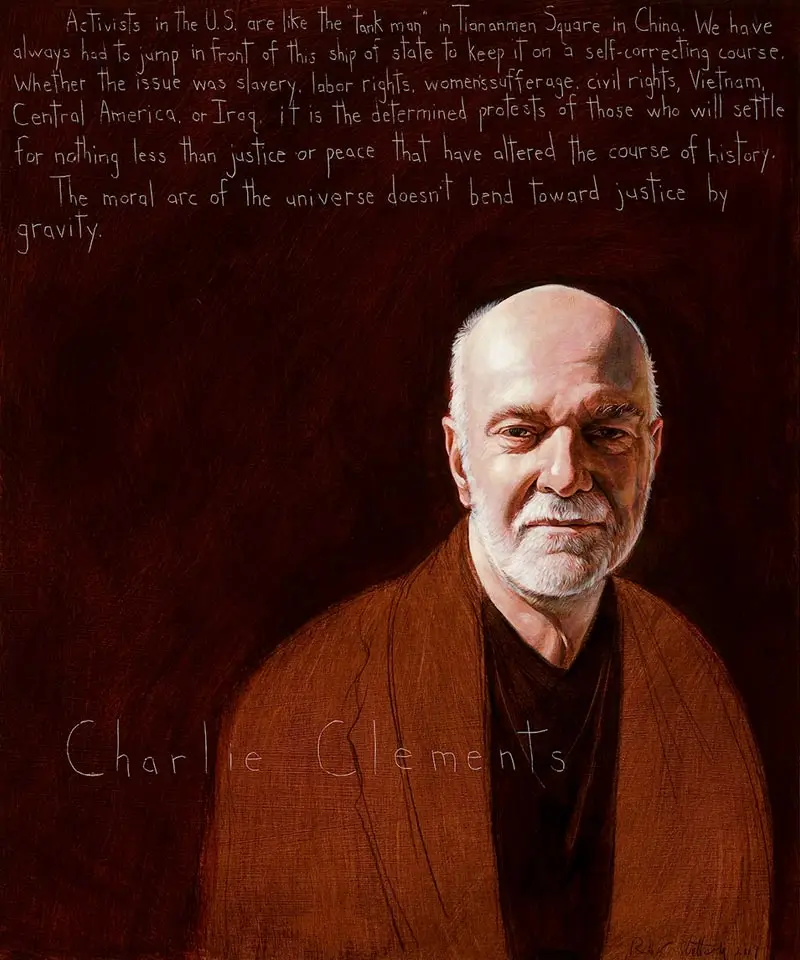

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.