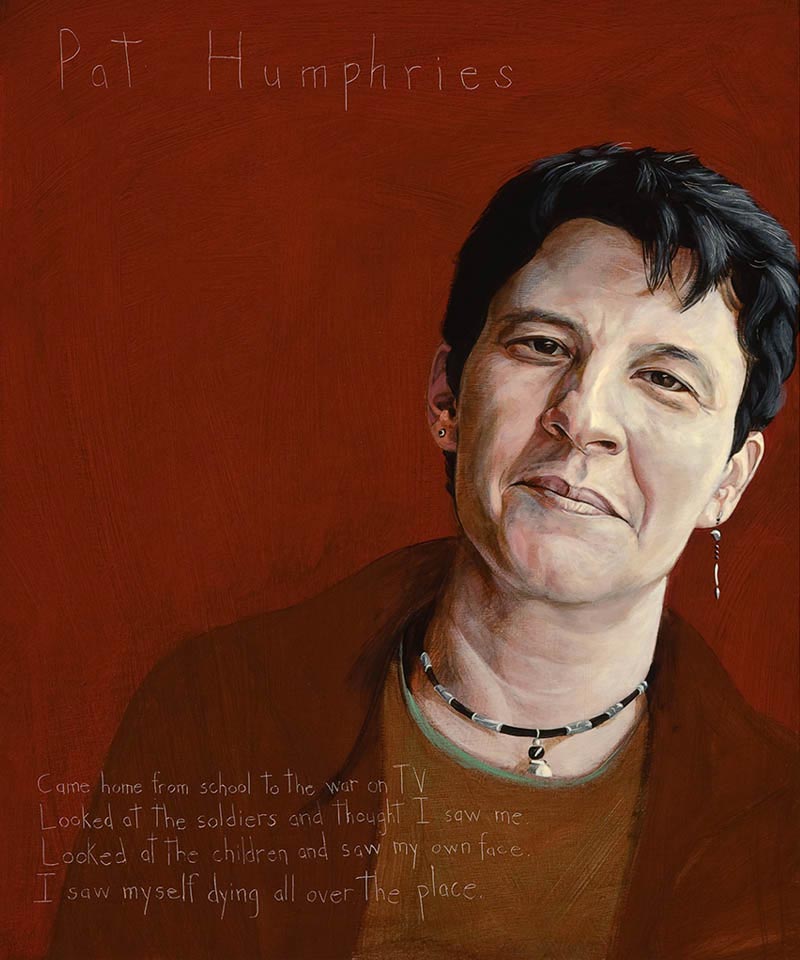

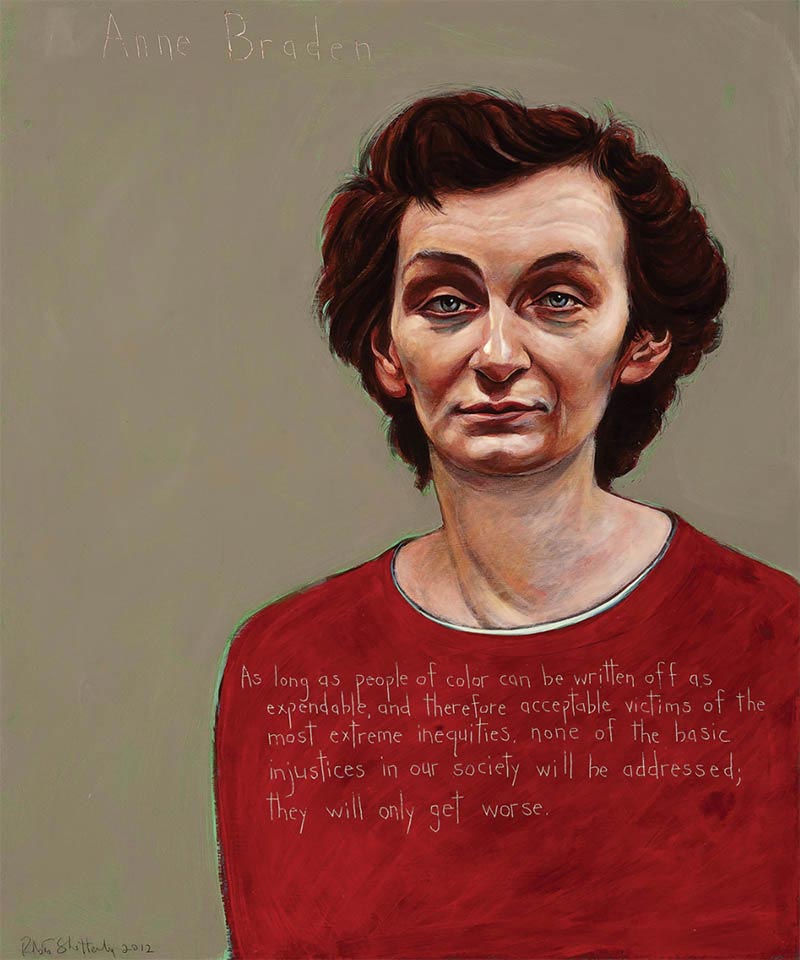

Anne Braden

Civil Rights Activist, Writer : 1924 - 2006

“As long as people of color can be written off as expendable, and therefore acceptable victims of the most extreme inequities, none of the basic injustices of our society will be addressed; they will only get worse.”

Biography

Anne Braden is best known for a single act: In 1954 she helped a Black couple buy a house in an all-white neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky.

Anne and her husband were put on trial for sedition, blacklisted for jobs, threatened, and reviled by their fellow white southerners for what they did. But, as she told the Kentucky Historical Society, “We never even thought of saying no … We didn’t really think about it [because] our minds were on other things.

The “other things” on Braden’s mind back then had to do with gaining equal access, regardless of race, to nearly every other aspect of life in the South: hospitals, schools, parks, public transportation, restaurants, hotels and more. “There was no organized movement to desegregate housing at that time,” said Braden, “but it would have been unthinkable to us to say no.”

“We lived in a segregated world,” she explained, “but we were part of a community of black and white people who were opposing it.”

Braden was an unlikely champion of racial equality. Born July 28, 1924, in Louisville, but raised in the even more racially divided Anniston, Alabama, she was a member of the southern elite. Economically, her family would have been considered middle-class (they didn’t have live-in servants), but because her mother was descended from what was known as the “first settlers,” Braden was raised to believe she was a member of a superior class of people. That idea started to bother her when she was still a girl.

While attending a church youth group to discuss “the Negro problem – which is what everybody called it if they talked about it at all,” said Braden, “I made some mild comment that it seemed to me people ought to be treated equal no matter what color they were. And I can remember people looking a little startled and then somebody coming up to me later and saying, ‘You shouldn’t say things like that, people will think you’re a communist.’ ”

Braden was also accused of betraying her race. Her first arrest—for protesting the execution of a Black man she believed to be wrongly convicted of rape—was in 1951. At the jail, she was threatened by a policeman. “He got absolutely furious,” said Braden. “It’s the whole traitor thing. He said, ‘And you’re in here, and you’re a southerner, and you’re on this thing!?’ And he turned around like he was going to hit me, but he didn’t because this other cop stopped him … All of a sudden that was a very revealing moment to me. All of my life police had been on my side. I didn’t think of it that way, but police didn’t bother you, you know, in the world where I grew up. All of a sudden I realized that I was on the other side. He had said, ‘You’re not a real southern woman.’ And I said, ‘No, I guess I’m not your kind of southern woman.’ ”

All of Braden’s activism flowed from a single conviction: she wanted to live in a world “where people were people,” not members of a particular race or class who were treated better or worse because of it.

Her long career as an activist, beginning at age twenty and spanned six decades. She’s well known for her efforts to end racial discrimination, less known for her many other battles. She fought for workers’ rights, helped organize labor unions, and was especially interested when Black and white workers joined forces to better conditions. She opposed war, fought for amnesty for those who refused to go to war, and worked for nuclear disarmament. She championed women’s rights and what she termed environmental justice; she considered environmental destruction a form of injustice in which the less fortunate suffer more than the privileged.

According to Braden, her path was always clear: “An older, African American leader that I respected highly told me I had to make a choice: be a part of the world of the lynchers or join the Other America—of people from the very beginning of this country who opposed injustice, and especially opposed racism and slavery. [He told me] I could be a part of that—that it existed today and offered me a home to live in.

“I felt like, well, that’s what I wanna be a part of. And so it was a very real concept to me all my life and still is. It is the present incarnation of the movement for social change in my time, but it’s also the connection with a past and a future. [It’s] like you’re part of a long chain of struggle that was here long before you were here, and it’s gonna be here long after you’re gone. And that gives life a meaning.”

In addition to being a political activist, Braden was the wife of labor organizer Carl Braden and was a mother of three. She worked both as a professional journalist and as a manual laborer. She wrote a book about her sedition trial, The Wall Between, which was nominated for the National Book Award. A biography of Braden’s life, written by Catherine Fosl, was published in 2002. The hip hop group Flobots recorded the song “Anne Braden” in her honor in 2007.

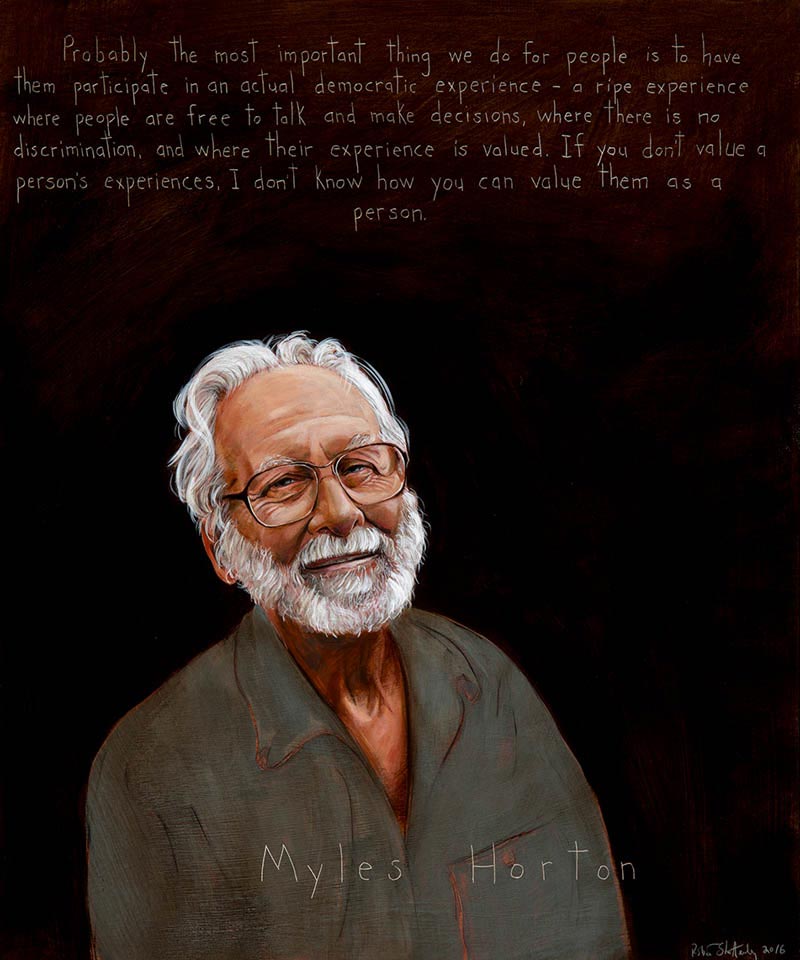

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.