What's New

How to Think about Frederick Douglass’s Feet of Clay

Not saints, flawed human beings. I’ve told people ever since I began painting the Americans Who Tell the Truth portraits: I don’t paint saints. They’re all real people. No heroes on pedestals. Just like us. Not religious saints, not secular saints. A few icons, maybe, but all real people. That means any one of us can lead the life of a portrait subject. What they all share is a common determination to bend the long moral arc of the universe toward justice. I celebrate that – their courage, their tenacity, their compassion, and their flaws.

People let you down sometimes. We let ourselves down. That doesn’t mean flaws negate the value of a life. Anyone’s life can be redeemed; anyone can become a role model by choosing to act for the common good. I don’t know specifically about the flaws of all my subjects. But I know enough to extrapolate – especially from my own flaws – that we all have clay feet. That’s the humanity we share. In fact, the flaws make the virtues all the more admirable.

That’s what I’ve said. However, there is one person I preferred to keep on a pedestal: Frederick Douglass. I extol his courage – the violently abused, enslaved teenager who escaped to the north, educated himself, became one of the 19th century’s greatest orators, a great leader of the abolitionist movement, an advisor to Lincoln on emancipation. He was beleaguered at every turn by critics and racists, was physically attacked in the south and physically attacked in the north while profoundly articulating the psychology and economy of racism. He understood power like no one else and was never intimidated by it. And after the Civil War he struggled mightily to keep Reconstruction on track to achieve full equality for Blacks. When he saw that dream being stolen, saw so much of that hope being crushed, the opportunity for real change purposely subverted in the north as well as the south, he tried harder – even at the expense of his own health.

Most white people, it turned out – even previously decent white people who had said the Civil War was fought to exorcise the horror of slavery from the nation’s soul – were not willing to fight against the horror of the Klan, lynching, and, eventually, legalized Jim Crow. They preferred what Douglass called “white people’s peace” – reconciling with white southerners as quickly as possible to get the economy running again, leaving former Confederates in charge of southern politics. It’s hard to imagine how crushing this was to Douglass and all other blacks. He railed and railed; no one listened. What was the purpose of all that bloodshed in the Civil War if it wasn’t to end the hypocrisy of legalized racism? If this was not a war of sacred intent, it was pointless slaughter.

I tell kids that the people I paint aren’t a freeze-dried sentence or two in a history book. They all lived complex lives. They struggled. They lost more battles than they won, and yet they persevered. They had families who loved them, families they disappointed. They often made a mess of trying to balance their public and private lives. They were smart, they were stupid. Sometimes they were hypocrites. And yet . . . I mean, what can you tell me about Martin Luther King, Jr.’s private life that diminishes his courage or importance to this country and the world? Read the biographies, I say. Good biographies stretch your heart to understand and accept the complexities of flawed people while you remain amazed by their passion for justice. You want to be like them. You can be.

David Blight has written an exceptional new biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, Simon & Schuster, 2018. Bright marvels, appropriately, at all the great moments of Douglass’ life. He casts Douglass, quite rightly, in the mold of the Biblical prophets. As he infused himself with their prophetic eloquence, he became one of them. Douglass became the angel this racist country had to wrestle. But Blight forbids the reader to relax into hero worship. He says, in effect, if you want to know this man, you’ve got see him whole. And that wholeness frequently hurts.

One of Douglass’ surpassing achievements as an orator was that he learned to entertain while he instructed, charm while he chastised, evoke laughter while urging them to do hard things. I was shocked and disappointed to read that throughout most of his career as a speaker, Douglass used stereotyping and racism both to entertain and to raise the estimation of African Americans in the eyes and hearts of his audience. Douglass made jokes about drunken Irishmen; surely an uneducated former slave was the equal of a drunken Irishman in the voting booth! He disparaged Indians. He said an Indian needed only a blanket to keep him happy, (He didn’t mention blankets purposely infected with smallpox.) He said Indians, unlike Blacks, were unsuited to progress and civilization. Indians were more like an animal species than fully human – content with being in nature. Without spelling it out, Douglass was close to endorsing Manifest Destiny, the idea that the North American continent was held in a sacred trust by God for white people. Indians were dispensable. Douglass just wanted Blacks, superior to Indians, to be included in that sacred dispensation with Whites.

And his speeches were not just for white people. He was speaking to Black people mired in a racism internalized over 200 years with the moral, spiritual and biological ideology of their own inferiority. Douglass thought they needed to hear that they were better, at least, than drunken Irishmen and Indians. He needed to change their consciousness, give them a yardstick to measure themselves comparatively.

Social change cannot happen until people’s consciousness changes. For instance, many men and even many women accepted that women were the weaker, inferior sex and didn’t need or deserve full political and social rights. What happened, then, to give men and women permission to change not only their sense of each other but to restructure their own identities? Persistent moral courage by some activist individuals played a huge role. Education did, too. Art helped. Organizing and persistence were necessary.

But on the flip side, the dark side, if we don’t want change, how do we give people permission to remain comfortably entrenched in their prejudices? That’s easy. We reinforce those prejudices effectively when a prominent person, a person of moral standing, reinforces those prejudices. Douglass gave people permission to redirect their racism from one group of people toward others.

Douglass’s use of racism is disturbing. He must have known better. It’s easy to say he was merely reflecting the thinking of his time – but unpersuasive. He was one of the strongest advocates in the country for women’s suffrage. In the years of the abolition movement prior to the Civil War, he was never afraid of taking unpopular positions. His racism, I suspect, was part of a strategy to separate Blacks in the minds of his audience from other minorities treated with opprobrium.

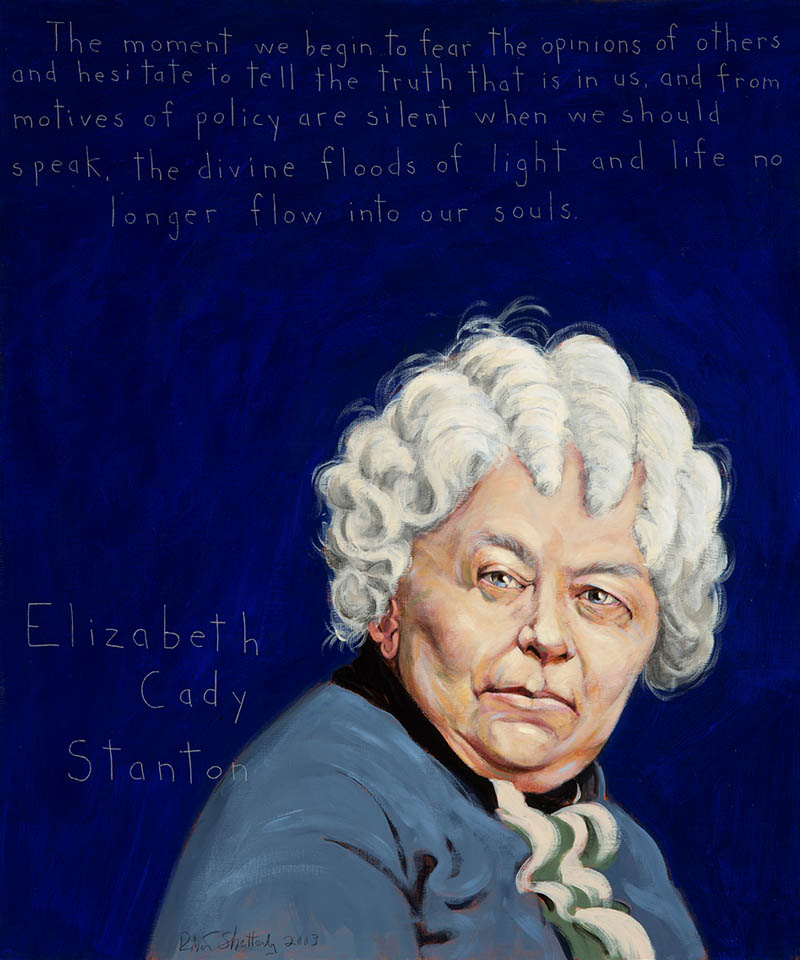

Of course, Douglass wasn’t alone in sending conflicting messages. Both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (both portraits in this series), fierce advocates for women’s rights, condemned Douglass in nasty racist terms when he maintained that winning the vote for Black men was more urgent than winning it for women.

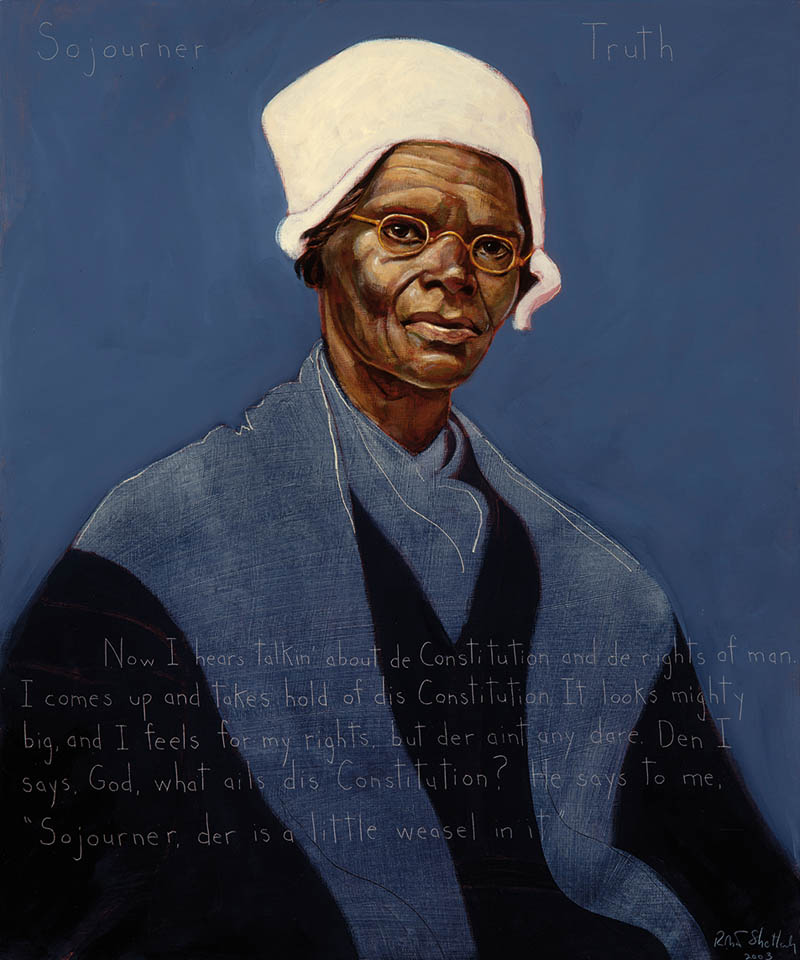

Previously, if I had had to choose whom to anoint as the Father of this country – the slave owner George Washington or the slave emancipator Frederick Douglass, the choice would be obvious. Do we want a father figure who betrayed his own ideals or the one who insisted we live by them? But, as we see, it gets messy. Maybe we’re better off with a Mother of the country? Sojourner Truth? Harriet Tubman? Are they without flaws? Of course not.

A couple of days ago, after a talk, I was asked by a woman if I’ve ever learned anything about a portrait subject that has made me remove them from the series. You know, she said, found out they were a fraud. I did my usual song and dance about how they are all flawed humans like the rest of us. And then I talked about discovering how Douglass used racism to advance the acceptance of Blacks. I said I’m reluctant to call his racism a blind spot. I think he knew what he was doing. It was a calculation. Painful. The calculation is more painful than a blind spot.

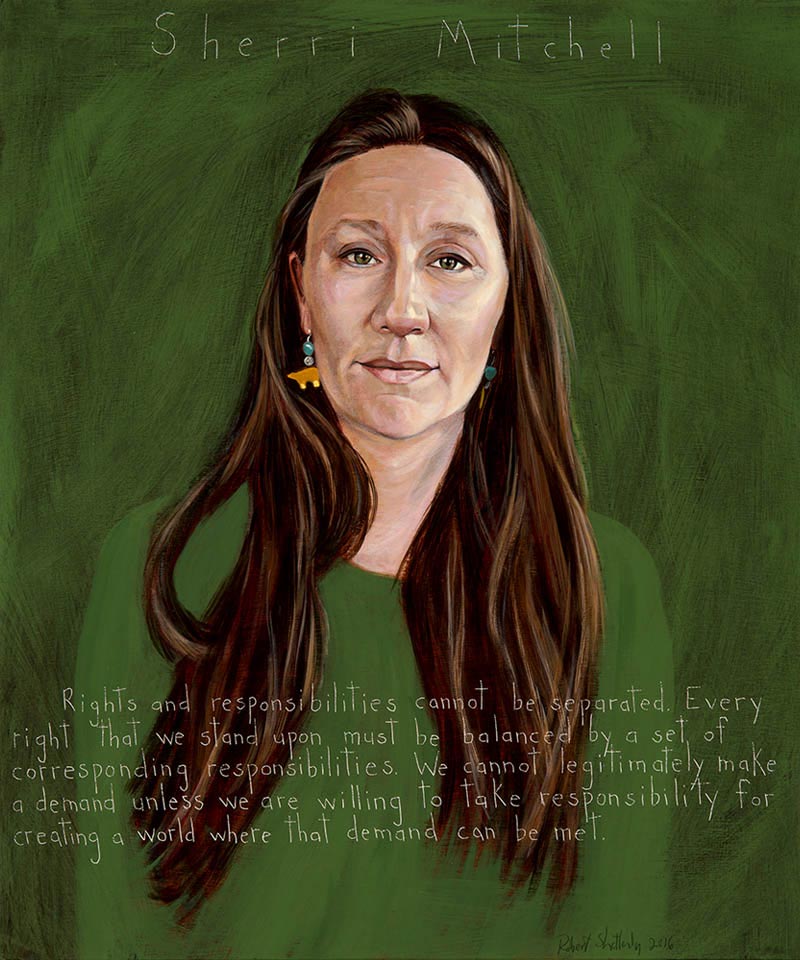

I called Sherri Mitchell (also a portrait in this series), a Penobscot native leader, author of Sacred Instructions, and asked if she could advise me on how to think about this conflict. Sherri laughed a bit cynically and said so many of the people we revere as liberators are also oppressors. And then she told me about the Buffalo Soldiers, the Black cavalry and infantry regiments formed in 1866 right after the Civil War to fight Indians. History touts their heroic stamina in forcing indigenous people off their native lands and onto reservations. One of the other means Douglass used to elevate Blacks in the eyes of whites was to tell the stories of the courage of Black soldiers in the last two years of the Civil War. White prejudice had maintained that Blacks were cowards. After the war Blacks extended that courage to kill Indians. Not only could they kill defenders of slavery; they could readily kill people as oppressed as themselves when ordered to. The Buffalo Soldiers were hoping to prove just what Douglass wanted – that their courage and patriotism would earn their acceptance.

So, where does that leave us? It seems to me, despite my disappointment, my job is certainly not to judge Douglass. My job is to understand. My job is to help us learn from his mistakes as well as his triumphs. My job is to model his courage if I can. No one else accomplished what he did in the abolition of slavery and the exposure of the mentality, economy and systemic nature of racism. In a way his flaws can even be seen as part of the evolution toward a less racist society. In biology many evolutionary adaptations are discarded when they prove counterproductive. So, too, in moral and intellectual evolution, many of the ideas expressed as good for race relations turn out to be either very narrow or even racist themselves. As we struggle to fully embrace the humanity of all people, as we struggle against historically embedded racism and struggle against contemporary politically motivated racism, we must recognize that the struggle goes on outside and inside ourselves. Racist propaganda can hide in us like a clever virus. Frederick Douglass instructs with his moral and physical courage and instructs with his painful mistakes. May we all be so blessed to be such instructors. If we demand perfection from our models, we deny them their full humanity and we deny ourselves our own.

As we struggle to create the world where our dreams of justice can be realized, we discover that the completion of those dreams is never complete, never will be. It’s not so much that the dreams are flawed but that the dreamers always will be. As we travel that arc, there is no better companion than Frederick Douglass. Let us tread where clay feet have trod.