What's New

Elizabeth Mumbet Freeman and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts

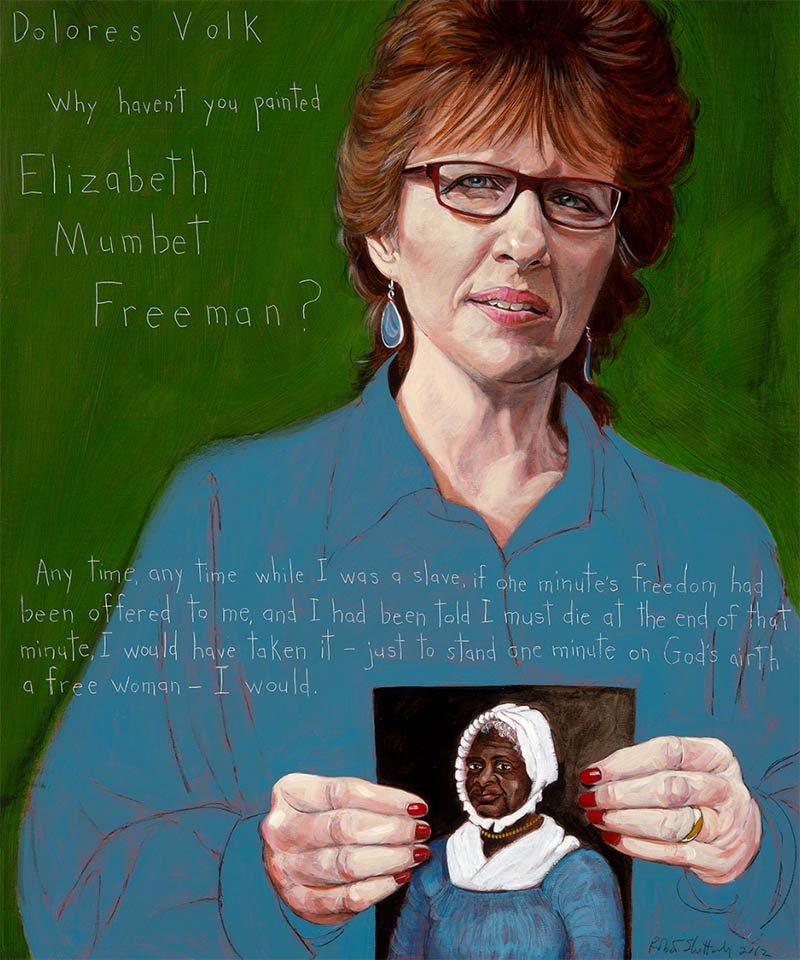

It’s true that the Americans Who Tell the Truth project has become all about education, but the primary education has been my own. In the past ten years I have learned more about our history, why our history is the way it is, and some of the people who have guided its evolution in order to be more in line with its own ideals than I had ever thought possible. Many of the people I’ve painted were totally unknown to me before I began the portrait series. And many of these were urged on me by people who wrote to me with the compelling stories of people I then decided I had to paint. I want to share the most recent story with you.

A few days ago I received this email:

Hello Mr. Shetterly,

I clean the restrooms on 3rd shift at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. I was moved to McGuffey Hall a few weeks ago and have been fascinated by your paintings because they look like they could come right off of the canvas and talk to me. Every night when I am walking that hallway I think of one thing…Someone is missing…It’s Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman. She would be a worthy subject for your series, in my opinion with the highlighted quote of course! My husband says they should erect a monument of her right next to Thomas Jefferson (America’s revered slave owner.) I think it would be wonderful to see her portrait on that wall some day! What do you think? Here’s more of her quote: “Well, Mr. Sedgwick, I was listening to the reading of the new law. I heard it said that all men are created equal and that every man has a right to freedom.

Now I ain’t no dumb critter! Won’t the law give me my freedom? Isn’t that what the law says, Mr.

Sedgwick?”

– Dolores Volk

I immediately wrote back to Dolores and asked for more information about “Mumbet,” but before I even got her answer, I began my own research. Elizabeth – “Bett” – was born in upstate New York in 1742 – forty-five years before Sojourner Truth – and, like Sojourner, onto a Dutch farm and into slavery. Her master, Pieter Hogeboom, “gave” Bett to his daughter Hannah when she married John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts. There she remained a slave until 1780, when, as the Revolutionary War ended, the Declaration of Independence was being taken to communities in all the colonies and read publicly. Bett was present at the reading in Sheffield, and, very moved by the language about unalienable rights and equality, she went right away to a young lawyer, Theodore Sedgwick, and said what is quoted above in Dolores’ email. Mr. Sedgwick, impressed with Elizabeth and opposed to slavery himself, decided to take her case, which became Brom and Bett vs. Ashley. On August 22, 1781, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a jury ruled in Bett’s favor, granting her not only freedom but also compensation for lost wages for all the years she worked as a slave with no pay. Her case was cited shortly afterwards by the State Supreme Court when it stuck down the legality of slavery in Massachusetts.

Bett then went to work – with pay – in her lawyer’s house and helped to raise his children. One child, Catherine Maria Sedgwick, loved and admired Bett and wrote her history after Bett’s death in 1829, which was published with the title “Slavery in New England” in Bentley’s Miscellany.

I recommend reading Catherine Sedgwick’s account of Bett’s life. It’s full of surprising, vivid anecdotes and wonderful quotations. For instance, Ms. Sedgwick writes, “I have heard her [Bett] say with an emphatic shake of the head peculiar to her, ‘Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it – just to stand one minute on God’s airth a free woman – I would.'”

Ms. Segdwick also tells the story of Bett standing between herself and her nasty mistress, Hannah Ashley, who was attempting to strike Bett’s sister Lizzy with a red hot shovel pulled from a cooking fire. Lizzy had scraped some dough for herself from the oaken bowl that was used to knead the family bread. Hannah accused Lizzy of stealing. Bett took the blow on her arm. Cut to the bone and burned, she did not cover it for the weeks that it took to heal and was left with a terrible scar. Bett said, “Madam never again laid her hand on Lizzy. I had a bad arm all winter, but Madam had the worst of it. I never covered the wound, and when people said to me, before Madam, ‘Betty, what ails your arm?’ I only answered – ask missis!”

There are a couple of points here that I would like to emphasize. The first is that I was told about Bett not by a student at Miami University and not by a professor, but by a woman, Dolores Volk, who cleans bathrooms – the kind of work that Bett did. I find that very moving and indicative of what this project is about. It’s not meant for our educational elites, but for everyone and invites everyone to be involved, to own it. It will take all of us – as better citizens – to control our destiny.

And, secondly, today is the 231st anniversary of the court case that ended Bett’s slavery in Massachusetts. Why do not more of us know this story? Whether it’s the story of Barbara Johns, or Claudette Colvin, or Samantha Smith, or Emma Tenayuca, or Bett Freeman, or so many other courageous, inspiring people who insisted that this country be the country it claims, we need to know these stories. We need to be emboldened and empowered by them to do the work of justice and equality to make the world a better place today.