What's New

White Privilege, Black Portraits, Whose Story?

Last September Connie Carter, AWTT’s education director, and I had the opportunity to visit the Maine State Prison and share the documentary Truth Tellers with a group of prisoners. Connie and I previously wrote about the revelations of that visit. But there was an aspect of the event which I thought deserved more serious attention because it strikes at the heart of what this project is all about.

In the prison we met and talked with a man named Leo Hylton. He perplexed us because he seemed totally unlike a prisoner stereotype – whatever that is – but, in fact, he was unlike any stereotype of adults anywhere. Leo is a mixed-race Black man with the imposing physical presence of a professional athlete – tall, handsome, trim, strong. But what struck us both was less the physical than the spiritual and intellectual presence. Leo speaks slowly, carefully and gently, with a seeming depth of wisdom – utterly calm and peaceful. We knew he had committed and acknowledged a violent crime – but no details. So, he is an anomaly, and we both wanted to find a way to talk more with him.

After the showing of Truth Tellers Leo asked, – no one else has ever asked this – “What is it about your white privilege that allows you to paint people of color?” He did not ask this in an aggressive way, but as though he was curious philosophically. “Are these your stories to tell, your people to paint? Or, is this another form of colonization and appropriation?”

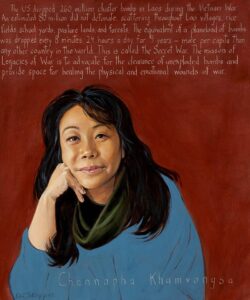

We live in a time focused intensively on identity politics, which has become an arbiter of authenticity, throwing up an electric fence against anyone without direct racial or historical experience who dares transgress into another’s territory. That is, what’s a white man from the coast of Maine doing painting portraits that include Frederick Douglass, Ella Baker, MLK, Jr., Bryan Stevenson and Fannie Lou Hamer. Or, for that matter, Cesar Chavez, Ai Jen Poo, Chief Joseph, and Channapha Khamvongsa?

I thanked Leo for asking that question. It made me feel uncomfortable – but not so uncomfortable that I became defensive. I wanted to explore it. Is there a basic flaw in AWTT: failing to acknowledge experiential boundaries? I could say that artists from all eras have claimed the prerogative of empathetic imagination to tell the stories of all people. But Leo’s question deserved a deeper answer than that. In what sense do people of a racial or ethnic group “own” their own heroes, their stories and the right to tell them? Taken to the extreme, such proprietary restrictions would mean that Shakespeare should not presume to put words in the mouths of Ophelia or Lady MacBeth. Or James Baldwin should not (could not!) write white characters into his novels. How else, then. can we attempt to fully empathize with each other’s common humanity if we don’t attempt such transgressions?

But the answer to this question is of a different order. And I began by saying that what Dr. King meant when he said “…none of us is free until all of us are free,” is that whether we consider ourselves either victims or perpetrators of enslavement, racism and oppression, the history shapes both of us, and both of us need to be freed from it if we are going to shape a just and peaceful community. The victims of enslavement and Jim Crow must be freed from the ideology and oppression of white supremacy. And, equally, the perpetrators of racial violence and white supremacy (that I represent by virtue of my whiteness and having profited from systemic racism) must be freed from that moral disfigurement. I told Leo that I had learned the nature of the sickness of our racist culture and what courage it takes to change it by painting portraits of people of color. They are my teachers, my models, my therapists, my guides on my own moral journey. I don’t paint BIPOC leaders to claim ownership. I paint them out of respect for their moral instruction and courage. Put another way – and this also reflects on the question of identity politics – I don’t paint BIPOC leaders, I paint leaders, many of whom are necessarily BIPOC.

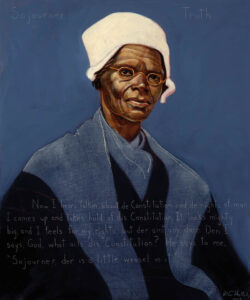

What would it look like to present the heroes of another race, culture, gender, or ethnicity inappropriately? Colonizing, dominant people did steal the lives, labor, education, the infinite possibilities of their accomplishments, the hopes and dreams of people they exploited. Oppressors enslaved them in forced inferiority and then used that inferiority to justify the enslavement. This is what we mean by a crime against humanity. Once done, there is no way to set it right, retrieve what might have been. If one were to paint portraits of the oppressed people’s heroes, their spiritual leaders and freedom fighters, their martyrs, without acknowledging the true historyt, at would be an appropriation. If, for instance, I were, as a white man, to paint a portrait of Sojourner Truth without exposing my own historical complicity in the crimes that enslaved her, I would be guilty of the worst aspect of white privilege. It would, simply, continue the oppression. My praise then, without accountability, would be a kind of – literally – whitewashing.

So, the people of color I paint are not a means of dodging the oppression of my white forebears by saying I am not like them. The portraits are not meant to obscure that possibility. The portraits are meant to help free me from my role as racist and colonizer – not by denying it but by accepting it. I’m honoring the people who worked to liberate me from the burden of systemic racism. Am I free? No, but the portraits point the way. And, by extension, I’m presenting them to all Americans to encourage the same journey.

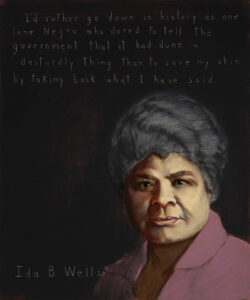

White people have taken so much from people of color that it’s likely that people of color would expect it to continue – by stealing their heroes, too. I don’t want to steal Ida B. Wells. I want to celebrate the courage of her blackness and what it teaches me about how to live. I rejoice in her struggle against white oppression because she identifies for me what side I want to be on. By the same token, I will not condemn the violence of the white man John Brown who tried to use his violence to spark an insurrection against the much greater violence of slave owners against Black people.

In a way you might say the portraits are meant to be an inquiry into the soul of this country. Is there such a thing as a country’s soul, and how could we measure it? If there is and if we can, it’s because the values of the country are enacted, or not, through the lives of millions of real people, historically and currently. If powerful people, in mockery of those professed values, purposely exploit and truncate the lives of others, the country then suffers moral injury, damages its soul. It makes itself a hypocrite and, like many hypocrites, attacks those who try to stop the dishonesty and exploitation. Many people of color do this soul-work by necessity, for survival. My conscience and the time afforded by my white privilege (another aspect of the answer to Leo’s original question) insist on and allow me to be part of that struggle. .

So, at the heart of all this is the question, “Who gets to tell the story?” Who has the right to tell it? Who owns it? Do Black people own Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth? How yes? How no? What part of that narrative should white people tell? Those people dedicated their lives to opening the eyes and hearts of white people. Shouldn’t white people honor them as eye-openers, heart-openers, redeemers? And then shouldn’t white people learn to do that work for themselves?

What we, white people, cannot claim is that we understand what their oppression feels like. Our burden is different; our complicity still plays out systemically – economically, educationally, medically, etc. That’s the story we must tell and determine how to remedy. So, then, there should not be any contention over who tells the story because employing the same people, we are telling different stories. The story of how MLK, Jr., liberates me from being a racist oppressor is not the same story as how he liberates a Black person from my oppression. Both stories need to be told and heard by each other. Then we might trust enough to build a Beloved Community. The question is not, then, if a person of white privilege has the right to tell certain stories involving the Black experience and Black courage; the question is how can a person with that privilege try to tell those stories in order to grow beyond the privilege and repair the systemic expression of it.

Perhaps the greatest and most harmful temptation of white privilege is choosing to ignore this history, not tell it or learn from it, not accept white responsibility. Many white people can be so insulated in their economic and social privilege that they need not face it at all. People of color do not have that privilege.The history chases them down. White people can pretend that racism and its effects are over. They can blindly assert their right to be “un-woke.”

So, when I examine the quandary of white, privileged people telling stories of people of color, I arrive at the necessity of doing so. White privilege can embrace the bitter damage of racism and be lifted out of it by the courage of its Black heroes. Knowing these stories, embracing these people, is necessary moral work for anyone who endeavors to be a citizen of this country.

Leo Hylton’s own thoughts can be found in his blog, “Shining Light on Humanity,” on The Bollard, Portland, Maine’s independent voice for local news and arts coverage.