What's New

Lessons from the Inside

AWTT Education Director Connie Carter wrote this blog post, with input from artist Rob Shetterly. They visited the Maine State Prison in September 2023.

I have long believed in the power of story; once you know someone’s story, you see them in a new light. Usually that light comes with understanding, compassion, and a bit of wisdom. I have spent over twenty years of my life dismantling stereotypes, to get beyond the labels that others put on us in order to be able to see the “real” person – strengths, beauty, and flaws all combining to make the human standing before me. So many people whom I might have otherwise passed over, ignored, thought not worthy of my time became friends, important forces in my life, and humans with stories that made them real and so very valuable.

The power of this perspective hit me hard this month when we visited the Maine State Prison. Rob Shetterly and I were guests of the prison where Truth Tellers – the documentary of Rob’s journey to uphold America’s founding ideals through his project Americans Who Tell the Truth – was being shown to any inmates who chose to attend. I wanted to attend because I was curious. I had never been in a prison, I had never had conversations with prisoners. I had preconceived ideas about meeting angry, gruff – maybe scary – people. Yes, I had met people who had been arrested – Rob, for one – but all for a cause or an injustice that was working against the common good. The very fact that this film was being shown in the prison should have alerted us to the unexpected.

The imposing facade of the prison is surprising – clean white granite with the words Honesty, Respect, Integrity, Dependability, and Trust chiseled into the stone. One wonders about the relationship of those values to the men inside and to the administrators. Are these the real aspirations of this place?

From the moment we walked through the first locked door, the curtain of stereotypes began to part. We were greeted warmly by the “check-in” guard. Then, after giving up our car keys and our licenses, we walked through several more locked doors into an outside space with beautiful flowers and vegetable gardens, all maintained by inmates. The harvest is used in their kitchens and given to other locations in need of fresh produce. If we hadn’t looked up and seen the rolls of razor wire keeping us in, we would have thought we were in a nature wonderland. Aesthetic spaces with rows and rows of multicolored flowers and vegetables was not our vision of a center for punishment. This space of beauty and health demonstrates a profound concern for a kind of rehabilitation that isn’t simply about punishment and job training.

All people need beauty and health in their lives.

Then … the real awakening! We met the inmates. They all shook our hands, looked us in the eye, thanked us for being there, and wanted to engage in conversation – about their middle school years, about their children, about time in the armed services, about leading the prison’s NAACP chapter, about the legislation they were writing to facilitate better reentry of prisoners into society. As the film began, the atmosphere was casual; people got up for coffee when it was ready, sat back down, always apologized for walking in front of us.

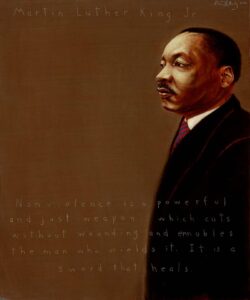

The film ended. Rob talked briefly about his journey, and then the questions. The first one was about seeing Rob being arrested in the film and what had he done? Even though his arrests were quite a different story from theirs, that moment may have built a bit of a common ground; it was a tiny place of understanding. A few more questions and then Leo – very articulate, compassionate, thoughtful. We both thought he was someone “from the outside” who was there to work with the prisoners. He asked how Rob felt about using his white privilege to share the stories of BIPOC history and current events. His questions cut to the heart of what AWTT is about. They explored the compassion behind the project; they exposed the fierce love that we all need to help bring us to a common understanding. At that heart is what Dr. King meant when he said that none of us is free until all of us are free. The history of this country, its difficult story of violent racism and exploitation, victims and perpetrators, belongs to all of us – all of us trapped in its continuing complicated drama. All of us are responsible to tell and understand the stories of each other.

Assuming that Leo must be working with a local agency to help prisoners think about regaining their humanity and being able to approach restorative justice, I casually asked him how he happened to be working with the inmates. Without a moment’s hesitation, he answered, “I live here.” I don’t think I showed the shock on my face, but inside, at that moment, my whole thinking about our prison system changed. Prisons need to be places where people can, as Leo said, address not “why did you do that?” but “what in your life made you do that?” The inmates need to be supported and helped as they take the journey towards blending their “inside environment” with the outside world where they can become the caring, useful, productive people they lost at some point in their lives. Fully rehabilitating prisoners does not address the trauma of their past victims. It attempts to remove the trauma of future victims.

Perhaps that is an idealistic stance because they did violate the laws that protect humanity. They did “break the rules” and need to be held accountable for their actions. But, maybe before they can move to a place of restorative justice, they need to understand their own journeys – what happened to them to make them harm others, what caused them to lose their way. And, then, how do they incorporate the wrong they did into creating a path forward that builds on their strengths, that helps them contribute to the common good.

I am not naive enough to think that the Maine State Prison is without its flaws or that every inmate is ready to take the steps towards becoming a more compassionate human, but my eyes and heart have been opened to think about how to support that journey and to think about how Americans Who Tell the Truth can provide experiences, stories, and opportunities that will help build a bridge from the inside to the outside.

Before we left, Foster, head of the prison’s NAACP chapter, invited us to return and bring some of the actual portraits and tell their inspiring stories. Few places we have visited have seemed to better understand the potential of AWTT. We will go back. We want to learn more, not just out of curiosity but out of a desire to move us all towards the common good.