What's New

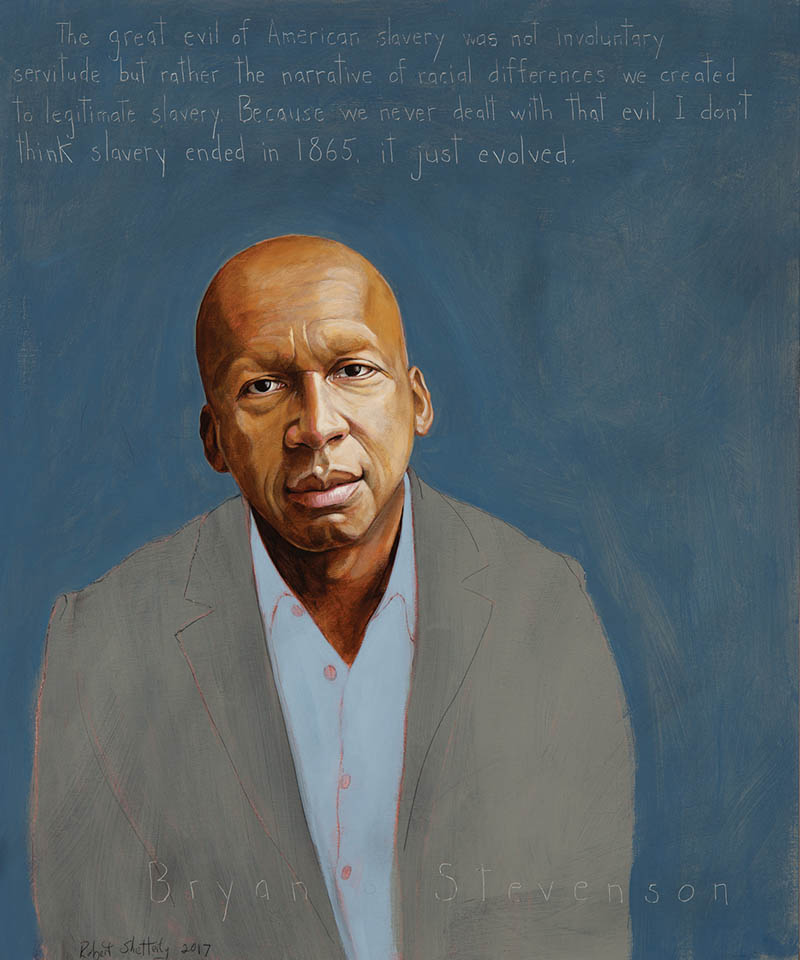

The Museum of Liberation

This morning I was listening to a podcast by Bryan Stevenson, a recent AWTT portrait. Many of you know that he and his organization, the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, recently opened a new museum which tells two stories. One part tells the story of the ongoing systemic transformations of racism in this country, from Slavery to Mass Incarceration. The other itemizes and graphically, viscerally, presents the legacy of lynching in the US – naming the victims, listing place and date, collecting soil from the spot where the murders happened – more than 4000 of them. About his work he says something surprising and very important – that its intent is not to punish America but to liberate it.

What does he mean? How does a museum focusing on the centuries long, determined and violent effort to maintain racist dominance not punish?

In the podcast Stevenson examines how Germany has been dealing for 60 years with the WW II legacy of the Nazis and the Holocaust and compares that with the U.S. history of genocide and slavery. The Germans make the terror and moral atrocity of their past transparent. Reminders, monuments, plaques, sculpture, memorials are everywhere. They refuse denial. They own it. They say, in effect, we flawed human beings committed these enormous crimes and it will take our eternal vigilance to ensure we don’t do it again. By doing so, they make repetition unlikely. The Germans publicly wrestle with their demons as a courageous community rather than each isolated person struggling with shame and guilt, fear and confusion.

In the U.S., however, very little mention is made in the media, in school books and public spaces, of the hundreds of years of native genocide, slavery, lynching, Jim Crow, and legalized systemic racism. No mention is made how all the wealth of this country is built on stolen land, stolen labor and the stolen lives of people of color. Our myth is not that we are flawed human beings but, instead, exceptional people because we are Americans who do no wrong. Stories of racism and genocide are suppressed and overlaid by stories of destiny and triumph.

Because we (white people) don’t take full responsibility for our past, we are haunted by it in the same way we read in stories about the souls of murdered people haunting the earth until the truth is told. What that haunting really means is that we have constructed a false identity, a false narrative, of who we are. This narrative refuses to embrace our true, flawed humanity. It’s both a personal and national myth: the exceptionalist myth that maintains white power, white privilege, white wealth and white innocence.

Bryan Stevenson makes the point that until we face our past and examine how it infects our present, we will be unable to change, our communities will be forever fractured. We will not know who we are and will

repeat the cycle of racist harm – against ourselves and other people of the world. We won’t be able to trust each other because we refuse to tell the same history. We inhabit antagonistic stories. That’s why telling the truth will not punish but liberate.

Ironically, one might think that because these racist myths have persisted for so long they are strong, they’re indestructible, history has hardened them into a super strong alloy of denial. I think the opposite is true. The myths are absurdly weak and vulnerable. They are defended adamantly because they are so easily exposed. We have become enslaved by our own false narratives. But abolition is not a monumental task. Expose these chains to sunlight and they evaporate. Not knowing who we really are keeps us repeating our history.

Dismantling the economy of racism is harder. Racism involves not just the power to claim superiority but the power to make profit at the expense of the the other. But we can’t begin to tackle that problem until we tell the truth of our history.

As a people we are stuck in several false narratives. Among them are the false narrative of the democratic benefits of capitalism, the false narrative of U.S. militarism, the false narrative that human beings are separate from and superior to the rest of nature. Our survival depends on eradicating those narratives, too. In fact, these narrative myths are intertwined with the racist myth. Removing one will help expose the others.

Visit Bryan Stevenson’s museum and begin your emancipation.