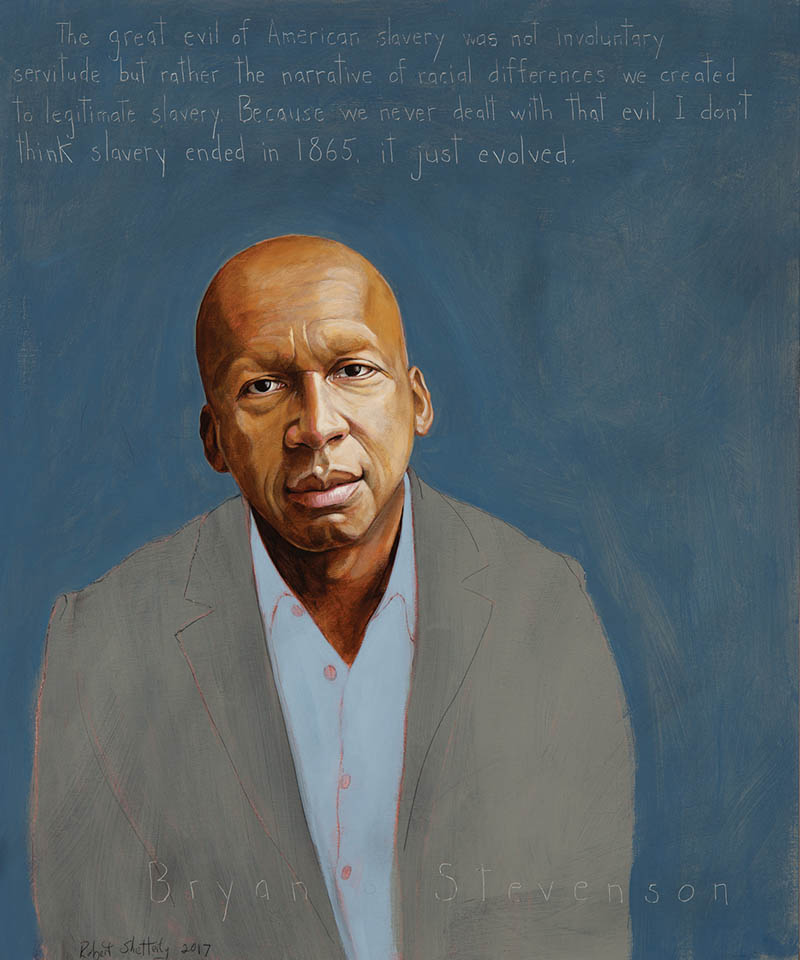

Bryan Stevenson

Death Row Lawyer : b. 1959

“The great evil of American slavery was not involuntary servitude but rather the narrative of racial differences we created to legitimize slavery. Because we never dealt with that evil, I don’t think slavery ended in 1865, it just evolved.”

Biography

Bryan Stevenson has said, “Whenever society begins to create policies and laws rooted in fear and anger, there will be abuse and injustice.” It’s not often that those who are poor or those who are incarcerated can find a champion who will stand up for them and affirm their humanity, particularly within the U.S. justice system. Bryan Stevenson is that rare champion. Through his work representing people who are often marginalized and ignored, Stevenson has been instrumental in tackling the very law enforcement policies that historically are deeply rooted in fear and anger. And his weapon has been the U.S. Constitution, a document steeped in the principles of the Enlightenment.

Through his work with the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing legal help to those who least can afford it, Stevenson has helped to transform the landscape of the criminal justice system, guided by a belief in the power of being equal before the law. “My work with the poor and incarcerated has persuaded me that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice,” says Stevenson. And justice is precisely what Stevenson has provided for his clients for decades, as he simultaneously addresses culture with “… work … aimed at trying to confront the burdens that people of color in this country face, which are heavily organized around presumption of dangerousness and guilt.” With his recent focus on preserving African American, U.S. Southern and American history, Stevenson is poised to extend that sense of justice from the present to our shared past.

Bryan Stevenson was born on November 14, 1959 to Howard Stevenson, Sr., and Alice (Golden) Stevenson in Milton, Delaware. After spending his earliest school years in a racially segregated school, Stevenson was a part of the first generation of African Americans in Delaware to experience legalized integration in public schools. He graduated from Cape Henlopen High School (Lewes, Delaware) in 1977 and matriculated at Eastern University in St. David’s, Pennsylvania. Stevenson studied political science and philosophy and graduated in 1981.

Stevenson moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts in the fall of 1981 to attend Harvard University, where he was accepted into a dual degree program in law and public policy with Harvard Law School and the John F. Kennedy School of Government. There he discovered his professional calling. During his second year he signed up for an internship with the Atlanta based Southern Center for Human Rights (Southern Center). There Stevenson witnessed the magnitude of the problem that criminal defendants and the convicted involved in capital legal cases faced in terms of the quality of their legal representation. Stevenson felt that “capital punishment means ‘them without capital get the punishment.’” So upon graduation from Harvard in 1985, armed with his dual degree, Stevenson joined the Southern Center as a staff attorney and was assigned to work in Alabama. In 1989, the congressional funding that supported the Southern Center was eliminated. But Stevenson, in his dedication to the work, established the Equal Justice Initiative in 1994 to guarantee legal representation to death row inmates in Alabama. Borrowing a line from another criminal justice activist, Sister Helen Prejean, Stevenson says, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

The following year, Stevenson was awarded a MacArthur fellowship, which he used to support EJI. Stevenson has been particularly effective at combating the draconian criminal penalties that had been imposed on children under the age of eighteen who are convicted of crimes. In the landmark 2005 decision, Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court agreed with the EJI and found that sentencing children under eighteen to death was unconstitutional. In 2012, in Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court, again, agreed with EJI and found it unconstitutional to give children mandatory life sentences without parole. With the 2016 Montgomery v. Louisiana case, the Supreme Court applied its Miller ruling retroactively to those in prison who had been sentenced as children to life without parole . Stevenson noted that “[w]e are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated. An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation. … The closer we get to mass incarceration and extreme levels of punishment, the more I believe it’s necessary to recognize that we all need mercy, we all need justice, and – perhaps – we all need some measure of unmerited grace.” That Stevenson was able to extend mercy and justice to children in the criminal justice system provided some of that necessary grace.

Stevenson has received a number of accolades and acknowledgements for his work in bringing justice to the least fortunate among us. In addition to the MacArthur fellowship, Stevenson has received the ACLU National Medal of Liberty, the Reebok Human Rights Award, and the Olaf Palme Prize from Sweden. Also, he has received a myriad of honorary degrees from colleges and universities across the nation. Stevenson is a noted and gifted speaker. His 2012 TED Talk went viral online; he also gave the keynote speech at the 2015 National Preservation Conference. Stevenson’s memoir, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, was a New York Times bestseller and was awarded both a NAACP Image Award for Best Non-Fiction and the 2015 Carnegie Medal for Best Non-Fiction.

Stevenson’s desire to seek justice has not been limited to those who currently are navigating the criminal justice system. In recent years, Stevenson has been looking to past injustices that have been neglected or ignored in the broader society, specifically the history of American slavery and southern lynchings in the post-Reconstruction era. He says, “Truth and reconciliation have always been sequential. You can’t get to reconciliation and recovery until you’ve got to the truth, and we’ve not done a very good job of telling the truth. If anything, we’ve distorted the history.”

EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration both opened in Montgomery, Alabama in 2018. The memorial is a place to honor the memories of those who were lynched across the South from the post-Reconstruction era through the civil rights period. The museum focuses on African American history through the lenses of American slavery, Jim Crow, and the criminal justice system. It is important to Stevenson that the various sites in Alabama tied to those aforementioned historical lenses receive historical recognition through historic preservation and the erection of historical markers detailing the history that hasn’t been told. Stevenson noted, “We’ve created the counter-narrative that says we have nothing about which we should be ashamed.”

Recognizing that injustice comes in many forms, Stevenson continues to fight for justice and truth, whether from our shared past or from the present day.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.