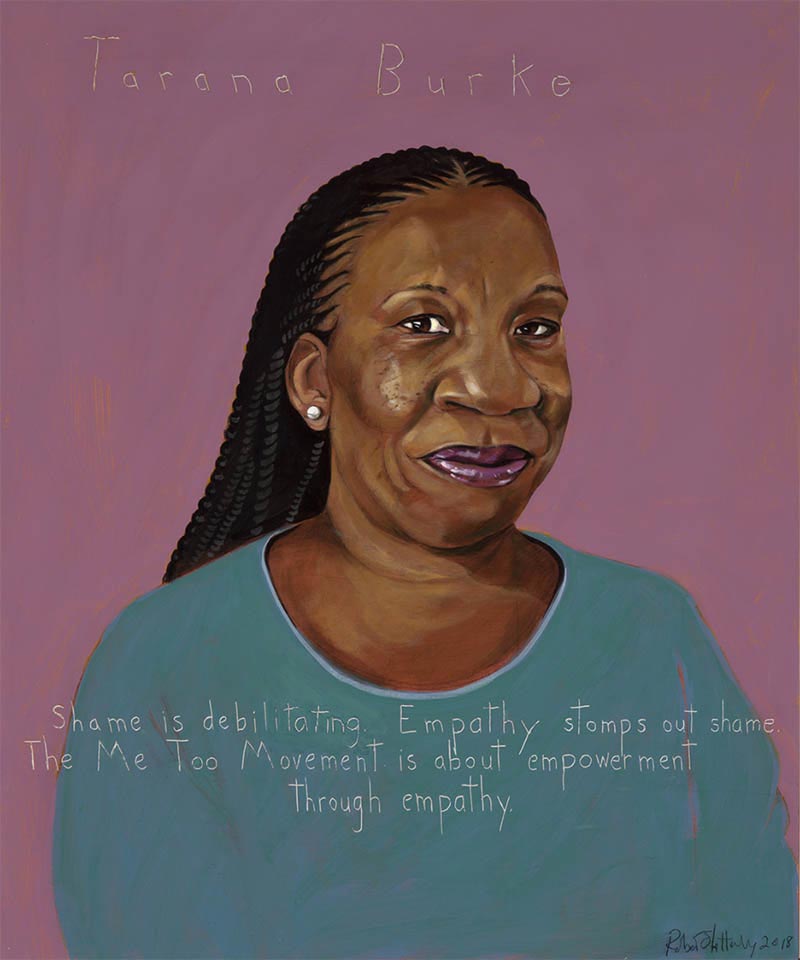

Tarana Burke

Activist for Women's Rights, Non-Profit Executive : b. 1973

“Shame is debilitating. Empathy stamps out shame. The Me Too Movement is about empowerment through empathy.”

Biography

Sexual violence is pervasive world wide. It is rooted in patriarchy, and its victims are both male and female. It is a global problem in need of a global solution.

Activist Tarana Burke has created a movement that will play a central role as we search for and implement that global solution. The Me Too movement is an outgrowth of Burke’s use of the phrase “me too,” which afforded her a way to speak to and make common cause with survivors of sexual violence. The phrase “me too” represented two sides of the same coin. “On one side, it’s a bold declarative statement that ‘I’m not ashamed,’ and ‘I’m not alone.’ On the other side, it’s a statement from survivor to survivor that says ‘I see you, I hear you, I understand you, and I’m here for you or I get it.” Burke says that “[s]ometimes you don’t want to have a whole conversation, and … saying ‘me too’ can be a conversation starter, or it can be the whole conversation.” And that is the brilliance of the phrase “me too.” The phrase is propelling a movement that represents both internal, personal power and the collective power that projects out into the world.

The founder of the Me Too movement, Tarana Burke, is a proud native of the Bronx, the New York City borough where she was born on September 12, 1973. She currently serves as a senior director with the Brooklyn, New York based non-profit Girls for Gender Equity, and she is the mother of Kaia Burke. Burke’s activism dates back to her adolescence, and her involvement with the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement, a Selma, Alabama based organization dedicated to helping young people become community organizers and leaders. It was through the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement that Burke participated in her first organizing effort in support of five African American and Latino teenage boys who had been accused committing a brutal sexual assault of a jogger in New York City’s Central Park. Those five boys, subsequently known as the “Central Park Five,” who eventually would be exonerated, were the subject of a campaign led by the future President of the United States, Donald Trump, to reinstate the death penalty in New York state. Burke’s effort against Trump and in support of the “Central Park Five” were her first lessons in practical organizing.

Following high school, Burke attended Alabama State University and graduated from Auburn University, in Auburn, Alabama. Burke remained in Alabama, moving to Selma to work for the 21 Century Youth Leadership Movement. During her time in Alabama, Burke co-founded the Jendayi Aza rites of passage program for girls (2003), founded the non-profit Just Be Inc. (2006), served as a special projects consultant with the National Voting Rights Museum & Institute, served as executive director of the Black Belt Arts and Cultural Center, and worked as a consultant on the 2014 film Selma. In Alabama Burke encountered a girl, to whom she gave the pseudonym “Heaven,” whose story forced Burke to confront her own circumstance as a survivor of sexual violence, even though Burke couldn’t yet bring herself to say “me too” out loud.

Unprepared to confront her own trauma, Burke’s desire to help other survivors kicked in. Determined that “‘me too’ could bring messages and words and encouragement to survivors of sexual violence,” it became clear that “me too” was not only “about survivors talking to survivors, but about using the power of empathy to stomp out shame.”

Recognizing the dearth of resources dedicated to helping young Black and brown girls, Burke used Just Be Inc. to help fill in some of the gaps. She wanted “to speak healing into their lives, to let them know that healing was possible, and let them know that they weren’t alone.” Meanwhile, Burke moved toward healing herself, which would make her a more effective healer. She sought out the things that gave her joy, noting that “[w]hen I learned to lean into my joy, my life changed.”

Burke had been working to spread the “Me Too” movement for more than a decade when in 2017 her message was amplified in ways that no one could have predicted. That year dozens of famous and powerful men were accused of sexual violence and sexual harassment. The Twitter hashtag #MeToo gave face to survivors of sexual violence, as well as let other survivors know they weren’t alone, which is what Burke had intended from the beginning. The call to solidarity around #MeToo was a resounding success as millions of people came out as survivors. Burke acknowledged the power of this catalytic moment, noting “what started as a simple exchange of empathy between survivors has now become a rallying cry, a movement builder and a clarion call. … With two words, folks who have been wearing the fear and shame that sexual violence leaves you with, like a scarlet letter, are able to come out into the sunlight and see that we are a global community.”

Burke has received a number of deserved awards and accolades for her work. Among them are the 2018 Prize for Courage from the Ridenhour Prizes and the Voices of the Year Catalyst Award from She Knows Media. Burke also received the Black Girls Rock Community Change Agent Award, and the North Star Award from the National Cares Mentoring Movement, both in 2018. And Burke was among the “silence breakers” who were, together, named Time magazine’s Person of the Year.

Yet, it is important that recognition and accolades do not overwhelm the critical work that Burke continues to do for the survivors of sexual violence. Burke makes sure that others do not create a false narrative for the Me Too movement. She reminds the world: “It’s not a hashtag. It’s not a moment. This is a movement.” She also asserts that “[t]his is not a movement about taking down powerful men. It’s not even a woman’s movement. It’s a movement for survivors.”

There have been discussions in the media about a backlash to the “Me Too” movement. But Burke remains determined to keep people focused on what this movement is. “All of these other conversations that are not about survivors, that are not about resources, that are not about community action, are distractions.” Looking toward the future for the Me Too movement, Burke believes “the conversation now needs to pivot … and I think that we now need to talk about the systems that are in place that allow sexual violence to flourish.” The good news for Burke is that she now has an army of survivors who are in position to begin dismantling those very systems, which is precisely what movements are created to do.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.