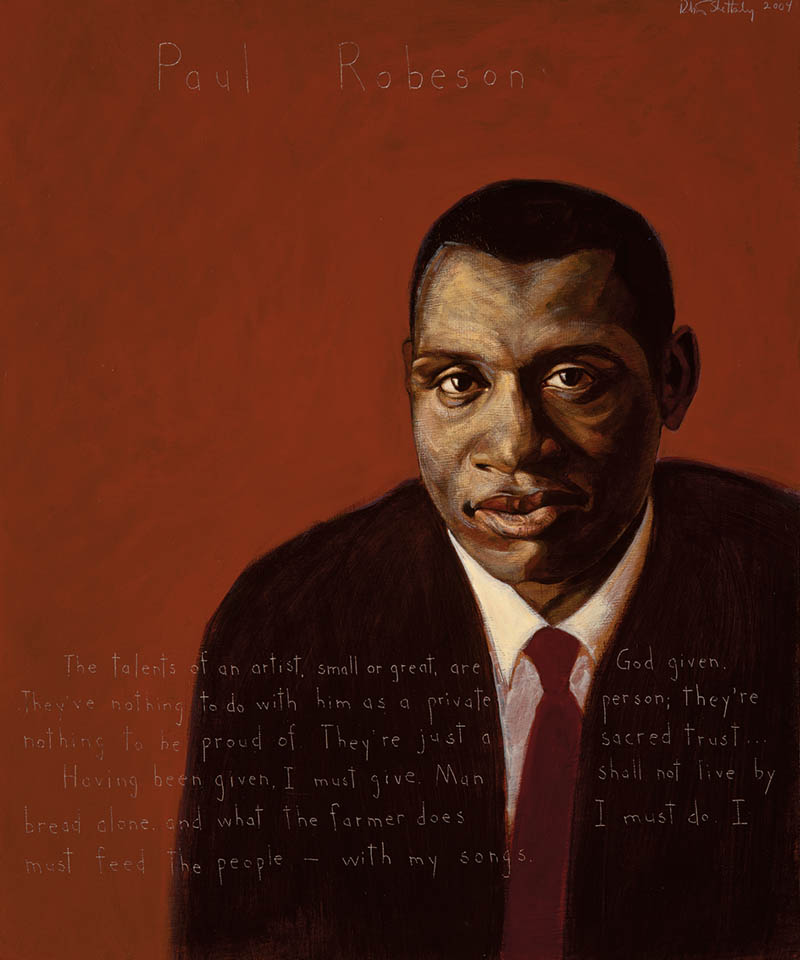

Paul Robeson

Singer, Writer, Civil Rights Activist : 1898 - 1976

“The talents of an artist, small or great, are God given. They’ve nothing to do with him as a private person; they’re nothing to be proud of. They’re just a sacred trust. … Having been given, I must give. Man shall not live by bread alone, and what the farmer does I must do. I must feed the people—with my songs.”

Biography

Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Paul Robeson was the son of a minister who had been a runaway slave. A keen student and gifted athlete, he won a scholarship to Rutgers, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year, and graduated in 1919 as class valedictorian. He was also an All-American football player who put himself through Columbia Law School by playing professional football on weekends.

When a stenographer in the New York law firm where he worked refused to take dictation from a “nigger,” he abandoned his legal career in favor of the stage. He joined the Provincetown Players where he won praise for his performance in the title role of Eugene O’Neill’s Emperor Jones. Success followed success. His generation knew him best for his portrayal of Othello on-stage and for his bass rendition of “Ol’ Man River” in stage and screen versions of Show Boat.

Traveling and performing abroad offered Robeson new perspectives. In his 1958 autobiography, Here I Stand, he wrote that “the essential character of a nation is determined … by the common people, and that the common people of all nations are truly brothers in the great family of mankind.” This perception led him not only to focus on the traditional American work songs and spirituals, but to learn more languages so that he could sing folk songs from other cultures. In the Soviet Union of the 1930s, he found a country free of racial prejudice: “Here, for the first time in my life I walk in full human dignity.” When he returned to the United States, Robeson became an outspoken critic of racism: he refused to sing before segregated audiences and led an anti-lynching campaign.

Many artists and writers who were drawn to Communism in the 1930s had renounced it by the end of the decade when Stalin signed a pact with Hitler. Paul Robeson did not, and his acceptance of the 1952 Stalin Prize made him an outcast in an America gripped by the Cold War. When a Congressional committee asked him why he hadn’t stayed in the Soviet Union, he answered: “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay right here and have a part of it just like you.” His passport was revoked from 1950-58; he was blacklisted as a performer and unable to earn a good living.

Paul Robeson once said: “The artist must elect to fight for Freedom or for Slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.