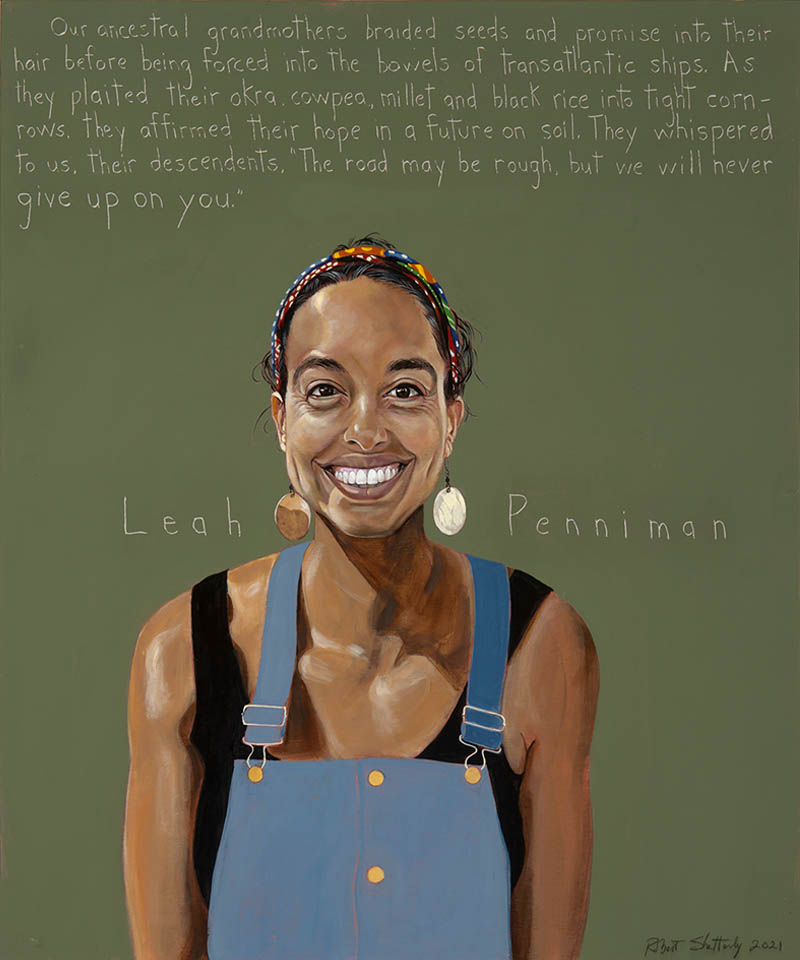

Leah Penniman

Farmer, educator, food justice activist : 1980 -

“Our ancestral grandmothers braided seeds and promise into their hair before being forced into the bowels of transatlantic ships. As they plaited their okra, cowpea, millet and black rice into tight cornrows, they affirmed their hope in a future on soil. They whispered to us, their descendents: “The road may be rough, but we will never give up on you.”

Biography

Co-Director and Farm Manager of Soul Fire Farm

Author of Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

Co-founder of Youth Grow urban farm in Worcester, Massachusetts

2019 recipient of the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award

Other awards include: Soros Equality Fellowship, NYSHealth Emerging Innovator Awards, The Andrew Goodman Foundation Hidden Heroes Award, Fulbright Distinguished Awards in Teaching Program, New Tech Network National Teaching Award, Presidential Award for Excellence in Teaching (New York finalist)

“From the first day, when the scent of freshly harvested cilantro nestled into my finger creases and dirty sweat stung my eyes,” Co-Director and Farm Manager of Soul Fire Farm Leah Penniman writes in her 2018 book Farming While Black, “I was hooked on farming. Something profound and magical happened to me as I learned to plant, tend, and harvest, and later to prepare and serve that produce in Boston’s toughest neighborhoods.”

Called “a love song for the earth and her peoples,” Farming While Black lays bare the social and racial discrimination perpetuated by a system of agriculture that has black and brown people in America dying from a pandemic of diabetes, kidney failure, and heart disease. The book provides inspiration and practical guidelines for African-heritage growers to reclaim their dignity as agriculturists. Penniman seeks to help all farmers honor the distinct, technical contributions made to sustainable agriculture by African-heritage people. She challenges us all to break free from society’s bounds and create a new food order.

Leah Penniman’s connection to the land began at a young age. Her grandmother, a refugee of the Great Migration that dispossessed black Southerners of their lands, kept alive her agricultural heritage by planting a strawberry patch and a crabapple tree in her yard on the outskirts of Boston. There she taught her granddaughters to garden, preserve their own food, and listen to the earth. Later, taunted and bullied at school because of the color of her skin, Penniman sought solace in the garden and in the woods outside her home. “I would literally go and hold onto grandmother, pine and cry my tears, and feel a sense of belonging and restoration from my connection with the land,” she said.

Summer jobs on farms strengthened Penniman’s reverence for the earth. But when she looked up, she saw no one who looked like her. Only 2% of farmers in the United States today are black or brown, a significant decrease from a peak of 14% in 1910. “This is not because black folks don’t want to farm,” Penniman says. “This is because of a whole legacy of discrimination, of institutional racism.”

When Penniman moved to South Albany, New York, she found herself cut out of the bounty she had once worked to provide others. Her low-income neighborhood lacked grocery stores and other food outlets that might provide her and her neighbors access to “the life-giving foods that make us whole.” Deemed a “food desert” by the federal government, Penniman questioned the use of the word “desert.” “Desert” implied a natural phenomenon, and she knew there was nothing natural about 40 million Americans facing hunger and disease because they lacked access to food. She understood this tragedy to be a human-created outcome of systemic racism. “Food apartheid” felt more real.

As she struggled to find fresh food to feed her own family, Penniman recalled her ancestral grandmothers, whose yearning to feed their children led them to hide the seeds of okra, cowpea, millet, and black rice in their braids before being forced onto transatlantic slave ships. She thought if they, in those unimaginable circumstances, had the audacious hope to set aside some seeds for her, how could she not plant these seeds for all of today’s children? Penniman started Soul Fire Farm.

Soul Fire Farm occupies approximately 80 acres of Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican territory in upstate New York. The Mohican people, the original stewards of this rocky land, were forcibly relocated to Wisconsin in the 1800s. Penniman set out to reclaim black and brown people’s inherent right to belong to the earth and have agency in the food system.

Penniman and her colleagues reintroduced ancestral biodiversity practices that spoke to the people and nurtured the earth. They planted crops to capture carbon—berries, orchard fruit trees, and medicinal herbs—and promoted regenerative practices to enliven the soil and help reverse climate change. The Farm provided more than sustenance. It put people in touch with their African roots and taught today’s farmers about black farming during and before slavery.

As Soul Fire Farm matured, its mission expanded. Victims of food apartheid were given food at no cost. Others were able to purchase fresh products through a farm-share CSA model that reached 110 households within 25 miles of the Farm. Patrons paid by the means they could, using food assistance vouchers or paying with cash on a sliding scale. Kitchens in the area filled with colorful, nutrient-dense boxes of food containing vegetables, eggs, pastured meat, and herbs.

Penniman provided in-person and remote farmer training in both Spanish and English. Grassroots organizers confronted the causes of food injustice, advocating lawmakers to establish policy and build systems to support brown and black farmers. In solidarity, Soul Fire Farm collaborated with local, national, and international farmers.

Since 2013, Penniman has trained approximately 600 new BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) farmers, with 86 percent of her graduates actively growing food at a farm or community garden. Soul Fire Farm’s efforts reach over 10,000 people annually in programs that include farmer training for black and brown growers, food justice workshops for urban youth, home gardens for city-dwellers living under food apartheid, reparations and land return initiatives for northeast farmers, doorstep harvest delivery for food insecure households, and systems and policy education for public decision makers.

Food apartheid continues to disproportionately impact communities of color, a condition exacerbated by COVID-19 because of factors like shared housing, lack of access to health care, environmental racism, job layoffs, immigration status, employment in the wage economy, and more. The emergency food system struggles to keep up with increased demand as food banks and food pantries are taxed by illness, unemployment, and fewer available volunteers. Penniman’s mission to uproot racism and seed sovereignty in the food system continues and evolves as she leads the charge with openness, flexibility, compassion, heavy lifting, sweat, and soil.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.