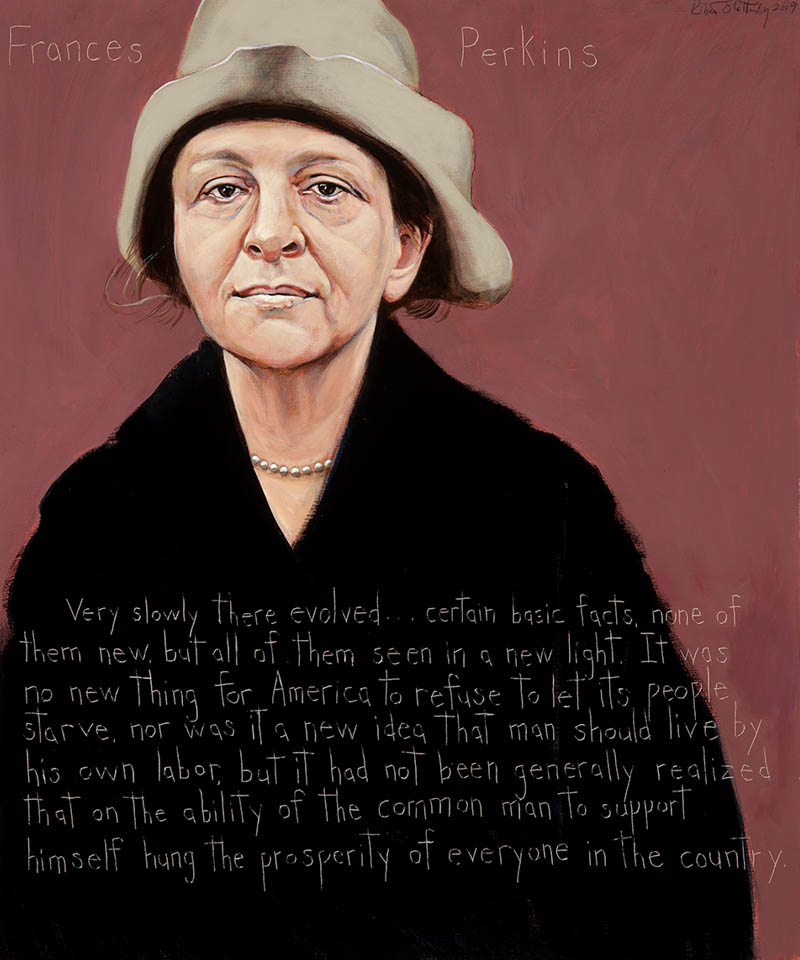

Frances Perkins

US Secretary of Labor 1933-1945, Teacher : 1880 - 1965

“Very slowly there evolved… certain basic facts, none of them new, but all of them seen in a new light. It was no new thing for America to refuse to let its people starve, nor was it a new idea that man should live by his own labor, but it had not been generally realized that on the ability of the common man to support himself hung the prosperity of everyone in the country.”

Biography

Only a handful of women have served in the Cabinet of a US President. Frances Perkins was the first. Her innovative and forward-thinking ideas shaped many of the labor laws that are in place today.

Frances Perkins (She was christened Fannie Coralee, but legally changed her name.) was born in Boston and raised in Worcester, MA, earning a Bachelor’s degree at Mt. Holyoke, and later a Master’s in sociology at Columbia. Perkins took a course in history while at Mt.Holyoke which set her on a lifelong path of working for labor reform. The class visited factories, where students could observe the working conditions. There, Perkins saw firsthand the effects of low wages and poor working conditions.

After graduating in 1903, Perkins went to Illinois to teach school, but received an education in social justice from leaders like Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr, and Dr. Graham Taylor, who was head of the Chicago Commons, a famous settlement house. It wasn’t long before she was living and working in a settlement house, beginning her career in social work.

In Philadelphia, she worked with young women who had been forced into prostitution by predatory landlords and employers. She then worked with NY State Senator Tommy McManus to improve social conditions in Hell’s Kitchen. The political education she received froim Senator McManus would come in handy later in her career.

By 1910, Perkins was general secretary of the National Consumers League in New York, and was becoming known as an expert on industrial working conditions.

In 1911, Perkins witnessed the infamous fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, where 146 young women died in worst industrial disaster in New York City history. Perkins watched as many workers, unable to escape down stairways because they were locked in, jumped to their deaths from the ten-story Asch Building. Horrified by what she saw, Perkins worked on the New York State Factory Commission–established in response to the fire–to improve job safety. She testified before the state legislature, and had lawmakers visit factories and workers’ homes to see their working and living conditions firsthand. Her tactics were successful. New laws and codes to protect workers, compensate them for injuries incurred while on the job, and to limit working hours for women and children were written between 1911 and 1915.

When she married in 1913, Perkins kept her name, unwilling to lose the influence it commanded in her field.

With the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Perkins would have a chance to take her ideas about social justice to a national level. In 1933, the new President picked Perkins to be his Secretary of Labor. She cautioned him, saying, “I don’t want to say yes to you unless you know what I’d like to do and are willing to have me go ahead and try.” She then told him about her plans for reform, including minimum wage, maximum work hours, unemployment benefits, social security, and universal healthcare. Roosevelt was certain she was the person he wanted, telling her that he would support her ideas. With that, Frances Perkins became the first woman to serve in a President’s Cabinet. She was Secretary of Labor from 1933-1945, serving under both FDR and President Truman.

When Roosevelt came to office, the country was in the midst of the Great Depression. He and Perkins worked swiftly to bring relief to the people of the United States. As Secretary of Labor, Perkins worked to create programs such as The Emergency Relief Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Public Works Administration. These programs provided food, shelter and jobs for millions of people.

Perhaps her greatest achievements were the enactments of the Social Security Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act. In 1935, Congress passed the first, ensuring that working people would have benefits during periods of unemployment and in retirement. In 1938, the second was made law, immediately raising wages and shortening work hours for many people. In many industries, the Fair Labor Standards Act prohibited the use of child labor.

Universal healthcare was one goal she could not achieve. And yet, with all that she achieved, she never believed that the federal government should dictate to the public. Rather, Perkins believed the federal government should work with state governments to pass laws that improve people´s lives. During her time as Labor Secretary she faced harsh criticism because her gender and her steadfast adherence to the rights and welfare of workers. At one point some members of Congress initiated an effort to have her impeached. The attempt failed.

When she ended her career in government service, she took a post on the faculty of Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, where she remained until her death in 1965.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.