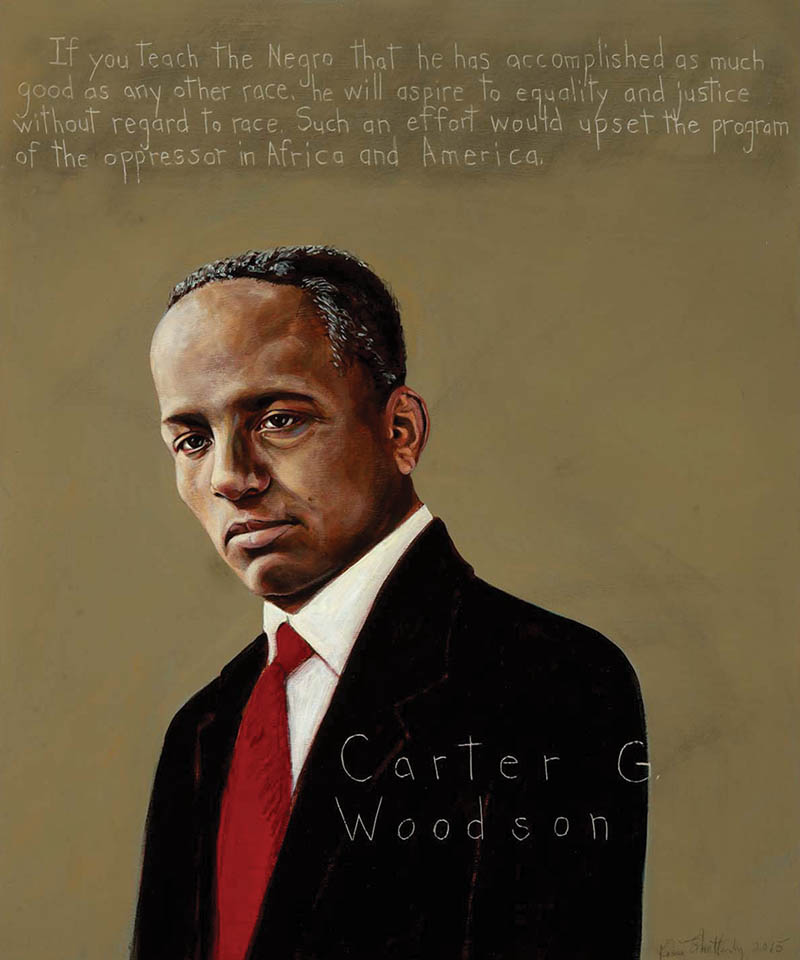

Carter G. Woodson

Educator, Historian, Author : 1875 - 1950

“If you teach the Negro that he has accomplished as much good as any other race, he will aspire to equality and justice without regard to race. Such an effort would upset the program of the oppressor in both Africa and America.”

Biography

During the eighteenth century, precious few Americans of African descent – Phillis Wheatley and Olaudah Equiano being exceptions – took pen to paper to chronicle their feelings or experiences in the colonies that would become the United States, leaving little record for historians to mine. But in the nineteenth century, a growing number of Americans of African descent began contributing to the historical legacy, from David Walker’s Appeal, to the various slave narratives that illuminated the lived experiences, the hopes, agonies, works, and desires of African Americans. Unfortunately, few early American historians considered the African American experience worthy of study, believing that it offered no significant contributions to the growing nation.

Historian Carter Goodwin Woodson would make it his life’s work to show not only how African Americans contributed to the history of the nation, but to teach African Americans about the contributions they had made. “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” he wrote.

Woodson was born in New Canton, Virginia, on December 19, 1875, to James and Anne (Riddle) Woodson. Both his parents were former slaves. After spending his early years in Virginia, Woodson moved with family to West Virginia where he found work as a coal miner and the opportunity to gain an education. When Woodson was nearly twenty, he enrolled in Frederick Douglass High School in Huntington, West Virginia. He completed high school in two years. In 1903, he earned a bachelor’s degree from Berea College, the South’s first racially integrated and co-educational institution of higher learning. Woodson served as a teacher and school administrator in the Philippines from 1903 to 1907, then entered the University of Chicago, where he earned a second bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in European history. Woodson completed his education at Harvard University, where he earned a Ph.D. in history in 1912, becoming the second African American – and the only one born to former slaves – to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard (W.E.B. DuBois was the first).

Armed with his deep knowledge of history, Woodson recognized that “[t]he mere imparting of information is not education,” and he set out to educate the world on African American history. “The thought of the inferiority of the Negro is drilled into him in almost every class he enters and in almost every book he studies,” he said as he worked to undo this problem. On September 9, 1915, Woodson, who was teaching high school in Washington, D.C., co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History). The goal of the organization was to bring together those who wished to research, publish and promote the history of African Americans in the United States, and to combat that “thought of inferiority.” That same year, Woodson’s first book was published, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. Woodson also founded The Journal of Negro History (now The Journal of African American History) in 1916 as a scholarly journal where professional and amateur historians could publish their research on African American history topics.

Woodson proved to be an excellent public relations advocate for African American history. Not only did he spend time as a teacher and administrator at both Howard University and the West Virginia Collegiate Institute (now West Virginia State University), but he also traveled across the country, held conferences, mentored young historians, published articles and books, and collected source materials to preserve the importance and value of African American history. In 1921, Woodson established Associated Publishers, among the nation’s oldest African American publishing houses, expressly to promote African American writers. And in 1926, Woodson promoted “Negro History Week.” He chose the second week of February because it corresponded with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, two figures of particular consequence to African American history. (This became Black History Month in 1976.)

The most lasting of Woodson’s work, The Mis-Education of the Negro, was published in 1933. This book indicted the education to which African Americans were subjected in the United States. Woodson argued that American education reinforced the inferiority of African Americans and wholly ignored the contributions made by them throughout American history. “The oppressor has always indoctrinated the weak with his interpretation of the crimes of the strong,” he wrote. The work represented Woodson’s position that African Americans must be more self reliant and self aware, not only to know who they are and what they’ve done historically, but also to advance culturally. Wrote Woodson, “As another has well said, to handicap a student by teaching him that his black face is a curse and that his struggle to change his condition is hopeless is the worst sort of lynching.”

Through his historical work, as well as his memberships or participation in organizations like the NAACP, the National Urban League, Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., and the New Negro Alliance, among many others, Woodson was very much a creator of the zeitgeist that caused African American history and culture to flourish in the early twentieth century. Woodson dedicated the rest of his life to the promotion of African American history, earning the title “Father of Black History.” By the time he passed away on April 3, 1950 in Washington, D.C., Woodson had established a strong foundation upon which African American history and culture, as subjects of intellectual inquiry, rest. The son of former slaves, Woodson discovered his own abilities, and encouraged others to follow suit, saying, “No man knows what he can do until he tries.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.