Those who have opposed the advancement of African American civil rights often have tried to obscure or misrepresent the stated goals of the African Americans leading those efforts. Too often media will accept these misleading narratives, even when those fighting to advance African American causes are crystal clear in their aims. An excellent historical example is reflected in the historiography of the Reconstruction era. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a concerted effort by many white Southerners, from journalists to politicians to historians, to create a false narrative about the history of Reconstruction. That false narrative described rampant corruption and mismanagement of Southern governments run by transplanted Northern Republican politicians (“Carpetbaggers”), “inept” African American legislators, and complicit white Southerners (“Scalawags”). This narrative would justify a wholesale assault on the rights of African Americans throughout the South, from the codification of racial segregation (Jim Crow) to political disenfranchisement to state sanctioned violence (lynching) intent on maintaining the racial hierarchy.

During the Obama administration, troubling parallels to the Jim Crow era’s state sanctioned violence were evident. Myriad shootings of African Americans both by law enforcement and citizens who feared African Americans were reported in the news and shared through social media platforms. The brutal lynching of Emmett Till ignited the civil rights activism of many young African Americans in 1955. In 2013, the murder of a Florida African American teenager, Trayvon Martin, by an individual who took the law into his own hands for dubious reasons (as with the murderers of Till), led to the creation of what has become the Black Lives Matter Movement.

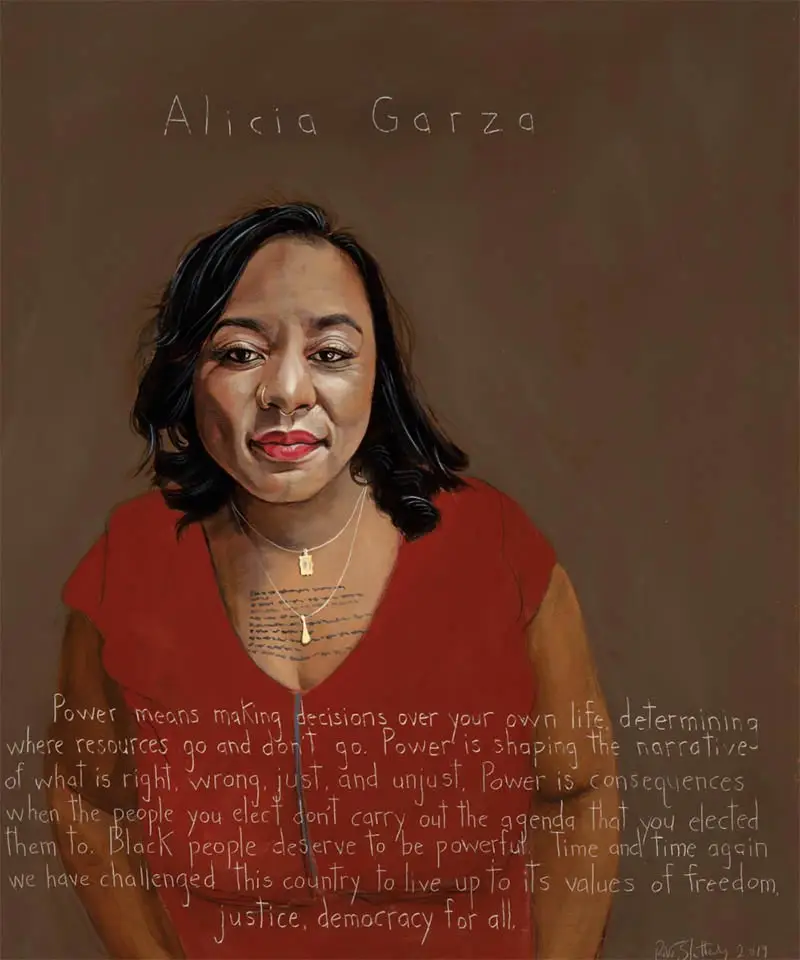

In July 2013, in the wake of the murder of Martin, Alicia Garza reacted on Facebook, using the phrase “Black lives matter.” Little did she know then that these words would launch a movement. Patrisse Cullors turned those words into a hashtag – #BlackLivesMatter – that went viral. Opal Tometi harnessed the mounting energy around these words by designing social media platforms and connecting activists interested in transforming #BlackLivesMatter real. Regarding the reach of the movement, Garza said “[w]e’ve connected people across the country working to end the various forms of injustice impacting our people. We’ve created [a] space for the celebration and humanization of Black lives.”

Garza further explains the movement’s origin: “I created #BlackLivesMatter with Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi … as a call to action for Black people after 17 year-old Trayvon Martin was posthumously placed on trial for his own murder and the killer, George Zimmerman, was not held accountable for the crime he committed. It was a response to the anti-Black racism that permeates our society and also, unfortunately, our movements. … Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.” Garza casts an inclusive net, explaining that “Black Lives Matter affirms the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, Black undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum.”

Despite the clarity of Garza’s explanation of the origins and meaning of Black Lives Matter, there were concerted efforts by opponents of the movement to obscure and misrepresent the movement as a whole. Some ignored the link to Trayvon Martin’s murder. Others created the hashtags “All Lives Matter” and “Blue Lives Matter” as a way to critique, often cynically, the very notion of centering a conversation on the idea that Black lives are not respected in our culture. Throughout the twentiethth century, those who opposed the aims of the civil rights movement would claim that those fighting for equality – the nation’s creed – were pushing instead for something “un-American,” for “socialism” or “communism.” These tired arguments have been recycled to critique Black Lives Matter.

The underlying concerns of the Black Lives Matter movement (now recognized as the Black Lives Matter Global Network) were not new, but its formulation as an international, decentralized social justice movement of the digital age established by three women of color has been revolutionary. “I’m in favor of people getting in where they fit in. Wherever you feel you can make the greatest contribution, you should,” Garza said to The New Yorker, opening the door to a variety of ways to participate in the movement. Unlike the traditional leadership of historical Black social movements, Garza pointed out to The Guardian that “[w]e have a lot of leaders, just not where you might be looking for them. If you’re only looking for the straight black man who is a preacher, you’re not going to find it.” Garza went further in an interview with The Cut, emphasizing the participation and agency of every participant: “[W]e also need a way in which we break this dynamic where people want to look to one person to tell them what to do. As long as we organize ourselves in that way, I think we’ll [not be] successful, because it doesn’t encourage innovation. It doesn’t encourage experimentation. And it also doesn’t encourage relationship building.”

In a 2016 TED interview, Garza talked about leadership. “I think that there is an element where leadership is lonely, but I also believe that it doesn’t have to be like that. … We have to stop treating leaders like superheroes. We are ordinary people attempting to do extraordinary things.”

The problem solver Garza , a current resident of Oakland, California, was born in Los Angeles on January 4, 1981, and was raised in Marin County. Garza is a 2002 alumna of the University of California San Diego, where she majored in Anthropology and Sociology. Garza came out as queer when she was twenty-three and credited the support she received from her parents’ interracial relationship: “I think it helped that my parents are an interracial couple. … Even if they didn’t fully understand what [queer] meant, they were supportive.” Garza met her husband, Malachi Larrabee-Garza, a trans male changemaker, through activist training the year following her college graduation. They married in 2008.

Garza is “driven by wanting to see change in my lifetime.” And she does the work to move toward that goal. Garza served as Executive Director of People Organized to Win Employment Rights (POWER) (2009). She served as board chair of the Right to the City Alliance (RTTC) (2011). Garza serves on the board of the School of Unity and Liberation (SOUL), which trains new generations of community-based social justice activists. Though Garza is recognized as a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, she also is the Strategy and Partnerships Director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance (Working with Ai-jen Poo, founder of NDWA.)

In 2018, Garza established the Black Futures Lab, a project focused on identifying ways to engage African Americans in meaningful grassroots change at the community level. In June 2019, the organization published the results of its Black Census Project, a survey of more than 30,000 African American participants, with the goal of showing the world that African American communities know and say what they need, while providing those interested in helping African American communities with an invaluable source of substantive information. On the landing page of the website for the Black Census Project, Garza states that “Black people have always played a role in unlocking the promise of an America that has not yet been realized, and if there was ever a time to tap into that power – it’s now.” In an interview with Fortune Magazine, Garza noted the following: “We want to make sure that campaigns, candidates and elected officials don’t see black communities as monolithic. … Polls and surveys attempting to designate what is important to black communities need to capture the complexity of our communities in order to have a more complete picture of what is important to us.” The Black Census Project captures that complexity.

Garza is the co-founder (with Ai-jen Poo and Cecile Richards) of Supermajority, an organization dedicated to advancing equity for women through advocacy, electoral politics and community organizing (with a focus on the 2020 Presidential election, among other electoral contests). In a June 2019 speech sponsored by The Nation, Garza explained: “Supermajority says that it will be women, cisgender and trans, that will shape what happens in 2020 and beyond. With Supermajority, we are saying that we are forming a wall of women. And you will have to get through women to accomplish anything at all in this country. … Nothing at all will change, if we are not paying attention to making sure that we can participate, and that we fight to expand who participates in the decisions that impact our lives.”

Garza will continue to be a driver of societal change, even as she understands these are long term efforts: “If anything, what I’ve learned from some of the people that have survived [the civil rights era] is that we have to be in it for the long haul. … Given the state of our political conditions, given the state of what’s happening in this country and around the world, we should be preparing ourselves for a long fight.”