What's New

George Washington Converses with Portraits

For many years a life size bronze George Washington has held silent court in the pristine, chapel-like foyer of the Maxwell School for Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. He stands mythically virtuous and consequential. By being the right, the essential, man at the right time, he is honored as the Father of this country. What strikes me is that this big man, this historical giant, this man who was all about leading and serving so many people, is so isolated here. Standing alone in this clean, white space he is segregated from his life, his time, and from our time – isolated from his ongoing effect, both good & bad – as though in quarantine, or cryogenically preserved and protected. Too easy to honor, and, perhaps, too easy to attack.

That is about to change. Gladys McCormick, history professor and Associate Dean of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, has invited AWTT to interrupt the sanctity of this hall with ten portraits which will, in effect, create a dialogue with and about Washington, who he was and who he is in relation to the lives of the portraits – what they mean to each other in both myth and reality across time. Professor McCormick imagines a Washington freed from the gloom of his silence, able to engage in dialogue, willing to listen to criticism and defend his choices. What can Washington and the portraits learn from one another? We do not yet know which portraits the Maxwell School will select to surround Washington, but it is safe to say that all of them will challenge this powerful white man’s failure to end slavery and to extend full political rights to women, indigenous people and freed Blacks, as well as to poor white men. They will easily point to the hundreds of years of contentious struggle and violence made necessary by Washington and the other Founding Fathers because of their failure to extend the promise of their language to everyone.

That much is obvious and must always be acknowledged because it’s that truth’s rending struggle that collages us together, makes us all blood brothers and sisters. In the evolution of the United States, that struggle is imprinted in our DNA as significantly as is the Declaration of Independence. Like a call and response. Or, we should say, imprinted in our DNA because the Declaration of Independence exists. But that truth is merely the beginning of what needs to be a much deeper conversation – unless we are satisfied with quibbling about hypocrisy and failure of will and vision. Washington was more than his failures. He was a man of dignity, strength and courage. And he was a man who caused immense suffering to African and Indigenous people. In the dialogue I imagine, Washington will honestly regret his moral and visionary failures; he will be grateful to, he will celebrate, the people in the portraits for nurturing his ideals to life because he could not. Rarely have the sins of the father been more consequential and dispiriting; never have his virtues and courage had such vast inspiration and longevity. But the potential of this dialogue will be wasted if its intent is merely to cut down the mythic Washington in the same manner he chopped down a mythic cherry tree. The wisdom we summon to assess Washington will be the measure of how honestly we assess ourselves.

Washington’s outsized triumphs and flaws wound into motion the positive and negative double helix of our history, the spiral dance of ideal with anti-ideal, a dance so charged with antagonism as to risk self destruction. Because that dance is as explosive today as it has ever been, this potential dialogue can have outsized repercussions. The two strands of the helix can also be defined as the struggle of the common good with self-interest – a struggle not just in our history but within every person. Washington, Jefferson and Madison, et al., hoped they could have it both ways: posit the ideals but maintain their economic security by enslaving fellow human beings. These brilliant men struggled with their contradictions. They used racism to justify them. How do we today wrestle with this twined inheritance?

It’s important that the Washington at Maxwell is his actual size, not like Mt. Rushmore.

We can look him in the eye; we can see him whole, think it extraordinary that he could conceive of the philosophic frame for a democratic country and have the courage to carry out the task of winning it; and we can find it equally extraordinary that he refused to make a place inside that philosophical framework for the full humanity of Africans and Natives. How do we both expand and diminish him at once? Perhaps we see Washington whole by not looking at him at all, but by looking at ourselves. How well, how courageously, do we strive for those same ideals? The measure of how to see Washington is in our acts. We judge him best by both correcting and collaborating with him. The portraits in constellation around him assume that task. Perhaps the hardest part is to bear up under the moral and historical weight of the suffering he helped to increase as well as relieve. That burden can’t be rectified any more than it can be justified. But it must be carried. I’d wager that the portrait subjects themselves could not positively assure us that, if they had been in Washington’s place, the outcomes would have been different. The truest measure of how we carry that burden will be in the love we show to those whose lives are still scarred by those initial injustices and the love we don’t show because of expediency or lack of empathy.

So, certainly the conversation with Washington will have to come to terms with his racism and self-interest. We will have to ask ourselves if we fail to judge it harshly: are we not betraying our lip service allegiance with his victims? The answer is yes, that would be a betrayal. And then we have to admit that many of us – most of us – are invested directly or indirectly in forms of economic self-interest. How can one live today without being advantaged by fossil fuels, by the industries of war, by systems of exploitation of all living species, by degradation of land and water? If we can’t personally divest from those deadly interests, how can we judge this man?

Washington becomes, then, a mirror in which we see not him but ourselves, or ourselves superimposed on him. And he is invisible unless we see ourselves. By “ourselves” I mean, primarily privileged white people, but I also include all people seduced away from their ideals by money, fear, security, fatigue and power.

So let us use this conversation to burnish Washington’s bronze and see ourselves reflected. We may see greatness we are unlikely to match and frailties we too easily match. Let’s honor his frailties by demanding more of the greatness in ourselves. In that reflection is where this conversation can begin. Washington can retain his status as Father of the country while the portraits will acquire the status, just as importantly, as the midwives to the necessity of correcting a country imperfectly fathered.

It has been a mistake, I think, to honor Washington alone, isolated like a saint, or confined like a criminal, for so long in this beautiful and austere place. The room is inhabited by triumphant ghosts, sacrificed ghosts, democratic dreams, dashed hopes, runaway slaves, slaughtered Indians, enormous wealth, stolen futures, promises crucified by special interests. The ghosts must be made visible, and they can be – through this dialogue. And in the air we can taste, like ozone after a thunderstorm, the vibrant tang of courage — Washington’s undeniable courage and the undeniable courage of those in the portraits his flaws and dreams called into being.

Perhaps one thing we will learn, as we engage this conversation, is how easy it is for all of us, any of us, to fall short. That the best we can do for ourselves and the future is to devise systems, political and economic communities, that regulate where we are weak, that protect where we would exploit, that love where we would dehumanize. If talking with Washington mirrors the nobility and the fragility of our best aspirations, then what we must learn from history is how to compensate for the fragility. I think George will understand that.

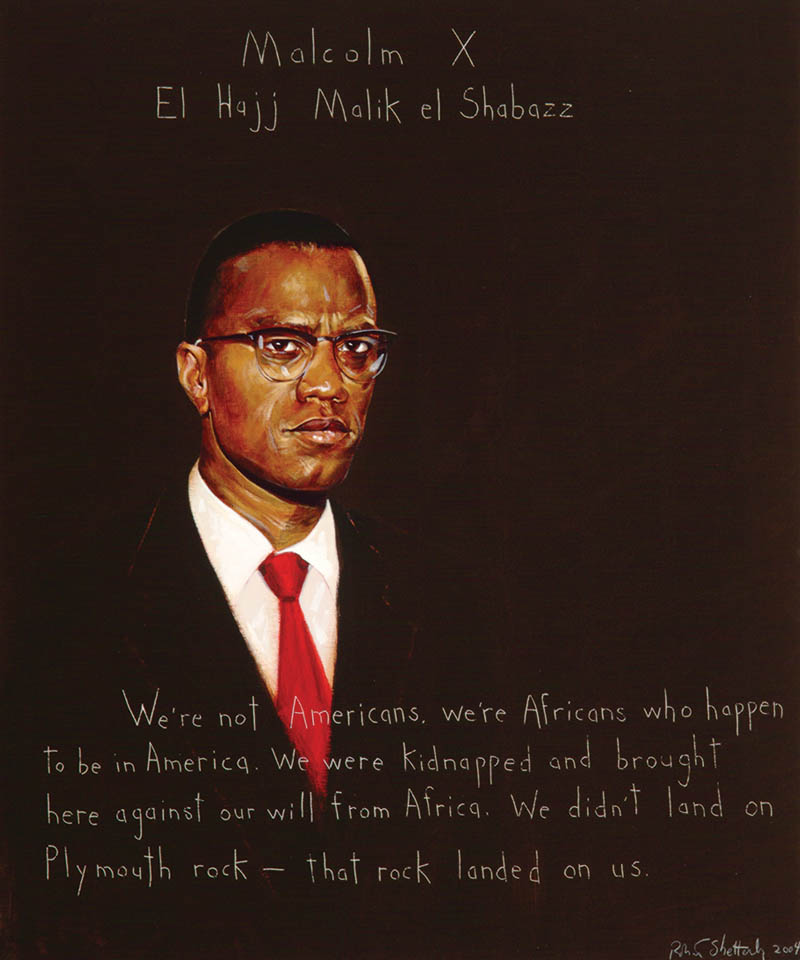

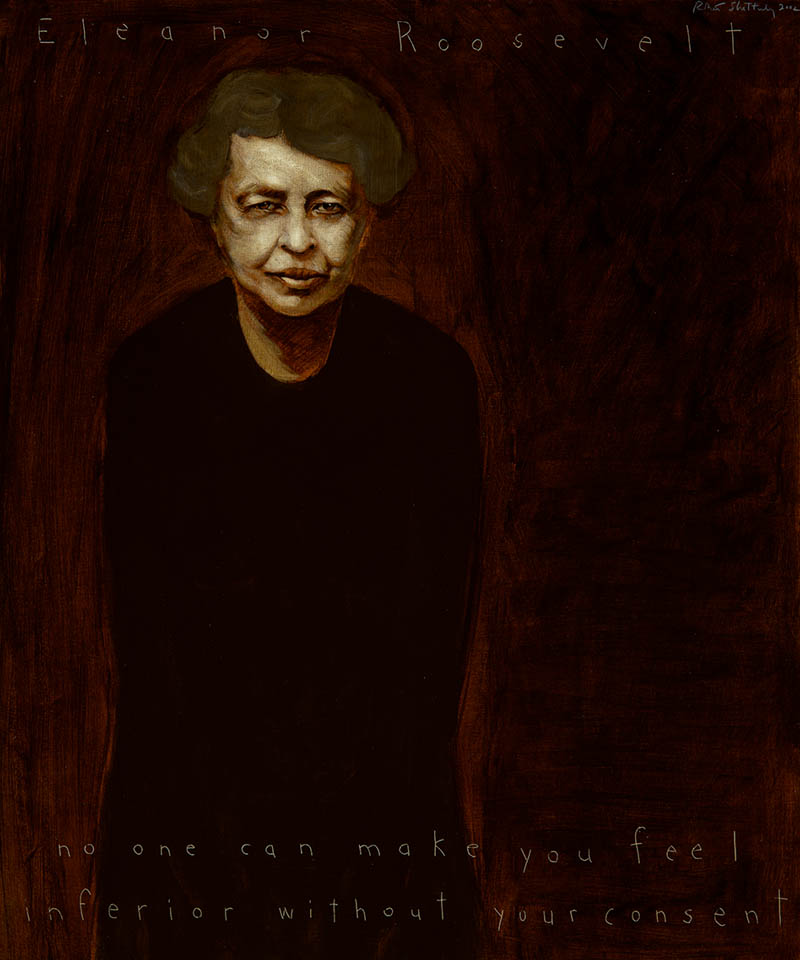

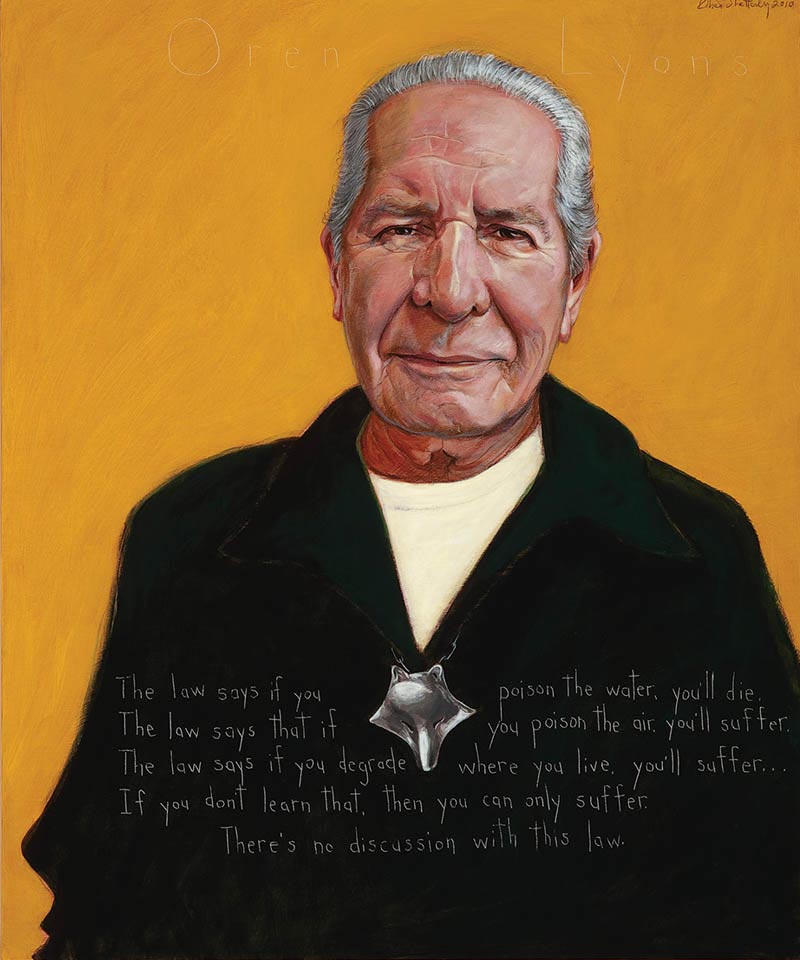

NOTE: Since AWTT artist Robert Shetterly wrote this essay, the portrait exhibit in the Maxwell School foyer has opened. Those portrait subjects who will be conversing with George Washington this fall include: Frederick Douglass, Sibel Edmunds, Nicole & Jonas Maines, Oren Lyons, Eleanor Roosevelt, Susan B. Anthony, Louis Brandeis, Gladys Vega, Grace Lee Boggs, and Malcolm X.

Read Syracuse University’s announcement about the significance of the exhibit