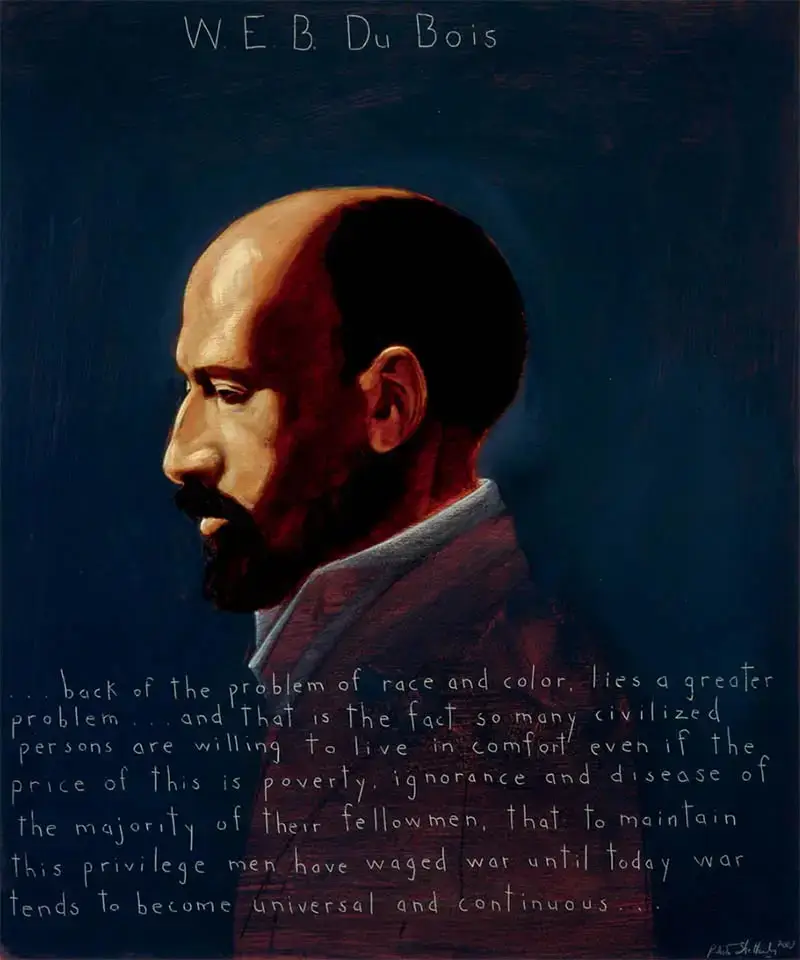

W.E.B. Du Bois

Writer, Teacher, Civil Rights Spokesman : 1868 - 1963

“Back of the problem of race and color lies a greater problem . . . and that is the fact so many civilized persons are willing to live in comfort even if the price of this is poverty, ignorance and disease of the majority of their fellowmen, that to maintain this privilege men have waged war until today war tends to become universal and continuous . . .”

Biography

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois is considered by many to be the father of African American studies. He spent his eclectic career researching and writing about both the history and the lived experiences of African Americans. As a professor, historian, civil rights activist, and editor, Du Bois used his prodigious intellect to advance the cause of African American equality within the United States, as well as to advocate for Pan-African collaboration and cooperation.

Du Bois was born to Alfred Du Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois in Great Barrington, Massachusetts on February 23, 1868. Unlike the vast majority of African Americans, Du Bois grew up in an integrated community, received a quality education, and was praised for his intellectual gifts. Following his graduation from the local high school (where he was the school’s first African American graduate), Du Bois, with the help of individuals in Great Barrington, was able to attend Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. This move marked Du Bois’ first encounter with the American South.

At a time when only a tiny minority of Americans went to college, Du Bois would receive an education that few of any race could have imagined, but particularly an African American. Following Du Bois’s 1888 graduation from Fisk, he entered Harvard University as a junior. By 1895, Du Bois had completed his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees (the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard). DuBois also won a scholarship to the University of Berlin and studied there for two years.

During the course of his doctoral studies, Du Bois accepted a teaching position at Wilberforce University in Ohio. At Wilberforce, he met his future wife Nina Gomer; they married in 1896 and had two children, Burghardt (who died in infancy) and Yolande. In 1896, Du Bois accepted a one year research appointment at the University of Pennsylvania, where he started what would become his monumental study, The Philadelphia Negro, the first sociological study of an African American community.

In 1897, Du Bois accepted a teaching position at Atlanta University, and it was there that Du Bois published his most important academic works, including the completed version of The Philadelphia Negro (1899), The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Black Reconstruction in America (1935). Du Bois once said, “Either the United States will destroy ignorance or ignorance will destroy the United States.” He was determined to do everything he could to eradicate some of the ignorance regarding African Americans. The Souls of Black Folk, for example, is a collection of essays that combines autobiography, sociology, history and fiction on the African American experience. Black Reconstruction in America, a direct attack on the broader and inherently racist historical interpretation of the Reconstruction era, ushered in a period of more accurate Reconstruction scholarship.

Du Bois was a co-founder of the Niagara Movement, a civil rights organization whose goals were in contradistinction to the purely economic self-sufficiency goals espoused by Booker T. Washington, the leading African American educator of his day. Though the Niagara Movement, established in 1905, ultimately failed, it did lead to the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was established in 1909. Du Bois served as both a board member of the NAACP and as editor of the organization’s magazine The Crisis. Du Bois left Atlanta University in 1910 to work full-time with the NAACP in New York City.

With The Crisis, Du Bois had a bully pulpit to offer his opinions and perspectives on a wide variety of issues beyond African American civil and political rights, including the labor movement and women’s rights. Du Bois used The Crisis to offer early support to the artists of the Harlem Renaissance. And from the platform of The Crisis, Du Bois advocated for Pan-Africanism, including African self-determination and the importance of building bridges within the African diaspora – the people of African descent scattered throughout the world primarily due to the slave trade.

Du Bois left his position with the NAACP in 1933 and returned to Atlanta University, where he worked for another decade, before returning once again to the NAACP as director of the Department of Special Research in 1943. Du Bois was one of three NAACP representatives who attended the gathering in San Francisco when the United Nations was established in 1945. Du Bois, long supportive of socialist principles, came under great scrutiny by the U.S. government following World War II for his critique of capitalism’s role in sustaining poverty within the African American community and for his associations with people, such as actor/activist Paul Robeson, who were sympathetic to communism. A strong peace advocate, Du Bois refused to discontinue his associations with people whose politics the U.S. government deemed questionable or undesirable.

In 1952, Du Bois and his second wife Shirley Graham Du Bois (Nina Gomer Du Bois passed away in 1950) were denied passport for international travel, a restriction that wasn’t lifted until 1958. Once allowed to travel, Du Bois visited a number of communist countries, almost in defiance of his treatment by the U.S. While visiting China in 1959, Du Bois expressed his feelings about the United States by stating that “in my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger.” In 1961, at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah, president of the newly independent nation of Ghana, Du Bois embarked on a new project, an Encyclopedia Africana. Du Bois moved to Accra, Ghana, renounced his U.S. citizenship, and remained there until his death, at ninety-five, on August 27, 1963.

Du Bois’ death was announced the next day at the March on Washington. This icon within the African American community did not live to see the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the Voting Rights Act of 1965, laws that represented precisely the goals he had sought in the early twentieth century. Perhaps President Lyndon Johnson, in signing these laws, had finally come to understand that, as Du Bois wrote, “… the cost of liberty is less than the price of repression.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.