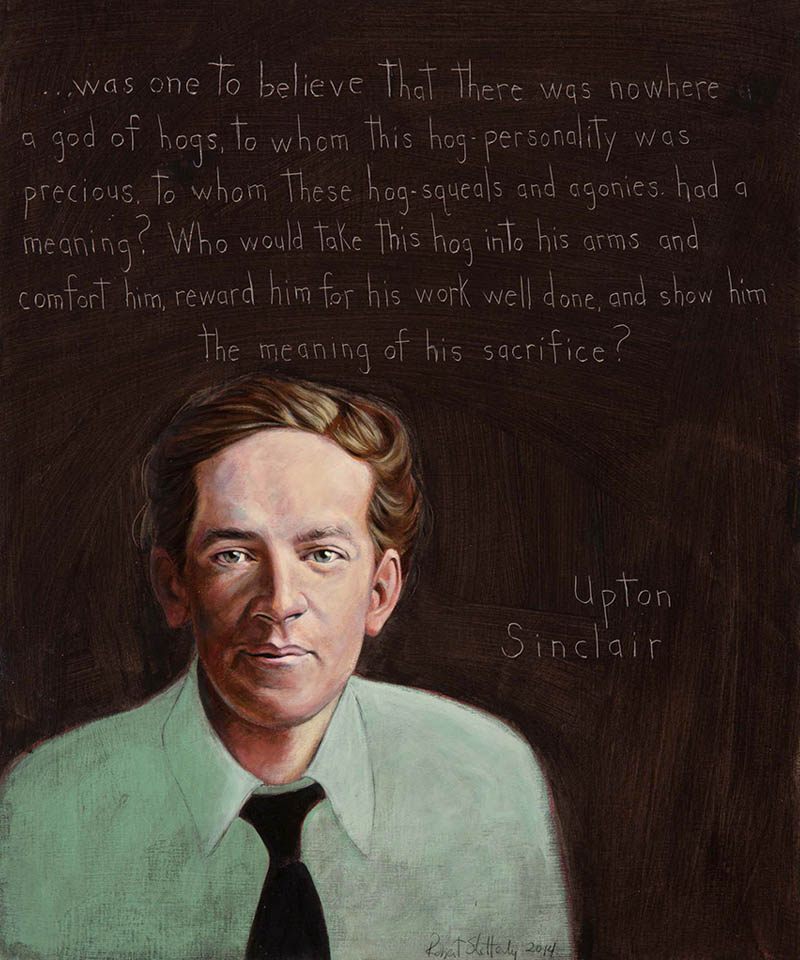

Upton Sinclair

Author : 1878 - 1968

“[W]as one to believe that there was nowhere a god of hogs, to whom this hog personality was precious, to whom these hog-squeals and agonies had a meaning? Who would take this hog into his arms and comfort him, reward him for his work well done, and show him the meaning of his sacrifice?”

Biography

Sinclair wrote over 80 books.

His 1927 book, Oil!, was the basis for the 2007 feature film, There Will be Blood.

In 1934, he ran for governor of California.

In 1943, he was awared the Pulitzer Prize, his only major literary award.

In 1967, when he was 89, President Lyndon Johnson invited Sinclair to the White House for the signing of the Wholesome Meat Act.

Upton Sinclair both disrupted and documented his era. The impact of his most famous work, The Jungle, would merit him a place in American history had he never written another book. Yet he wrote nearly eighty more, publishing most of them himself. What Sinclair did was both simple and profound: he committed his life to helping people of his era understand how society was run, by whom and for whom. His aim was nothing less than to “bury capitalism under a barrage of facts,” as Howard Zinn described it. One fact he tried repeatedly to teach was that capitalism and democracy are incompatible: “One of the necessary accompaniments of capitalism in a democracy is political corruption.”

When Upton Sinclair introduced himself to American readers in 1906 with the publication of The Jungle, his exposé of the meatpacking industry, he was only twenty-five years old. His intent was to awaken the public conscience over the horrendous conditions slaughterhouse workers were forced to endure. Sinclair was appalled that the public reaction to his book was to demand higher health standards for the meat products but ignore the workers. He said, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

For the next six decades, he would remain an unconventional, often controversial, and always innovative character in American life. He was also a filmmaker, a labor activist, a women’s rights advocate, and a health pioneer on the grandest scale.

At the beginning of the 20th century, investigative journalism was just being conceived, and Sinclair’s undercover reporting on the conditions in a meatpacking plant may have been its birthing moment. He was one of the original muckrakers. Filmmaking was beginning to change the way stories were told and how people gained access to information. His friends were experimenting with sexual freedom and birth control, but the shadow of alcoholism was beginning to take its toll in the radical community, and Sinclair would record his own assessment of the dangers of alcohol in his novel — and later film — The Wet Parade.

Sinclair critiqued institutions ranging from organized religion to journalism to education. These analyses remain surprisingly relevant. The problems with education and with media concentration, which Sinclair identified so presciently in 1920, have become impossible to ignore nearly one hundred years later.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, organized labor was struggling with the question of how to cope with the emergent hegemony of large-scale corporate capitalism. He had written many articles from Colorado about the coal miners’ strikes, the labor conditions and the Ludlow Massacre (1914), but the corporate friendly newspapers had refused to publish them. Sinclair responded by organizing a daily picket of Rockefeller headquarters in New York City to show support for embattled coal miners in Colorado.

That same year he wrote a science fiction novel, The Millennium, which predicted what life would be like in 2013 with startling accuracy. Sinclair demonstrated not only how a writer attempts to change history through literature but also lends his or her personality to the political struggles of the times. A conscious creator of popular history, Sinclair himself starred in one of the first pro-labor films every made, The Jungle, in 1914. He wrote Boston to document the Sacco-Vanzetti trial; Oil! exposed the depredations of the oil industry in California; Singing Jailbirds in 1924 recorded the imprisonment of Wobblies, members of the International Workers of the World union, in Los Angeles.

In his sixties, Sinclair wrote a series of antifascist spy novels, the World’s End series. The series was, as Dieter Herms has noted, “antifascist propaganda entertainingly packaged in the wrappers of popular literature.” The books garnered him best-seller status again, and in 1942 he became the oldest author to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

For Sinclair, his books were significant only to the degree that they exerted social influence, as the concluding pages of his autobiography reveal. He asks himself, “Just what do you think you have accomplished in your long lifetime?” and then provides ten answers. All involve social change in which his books were instrumental. Nowhere in this list of accomplishments is there a judgment that any of his novels represent an exclusively literary achievement. He often reflected, though, on why even the victims of unjust conditions were reluctant to demand change: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Part of Sinclair’s political analysis was that a healthy and sober personal life would make him a more effective agent of change — an early understanding of what would become a radical injunction that the personal is political. Sinclair, writes critic William Bloodworth, made “an unusually vigorous attempt to combine questions of food with political propaganda.” His mother’s temperance beliefs and his father’s alcoholism made him a lifelong crusader both for Prohibition and for temperance.

Indeed, Upton Sinclair was a man who challenged conventional masculinity. In that sense, he was ahead of his own time and vitally relevant to ours. He was a radical much influenced by women. His interest in communal living and communal childcare is quite unusual. His reading of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s theories on domestic labor and public life inspired his founding of the utopian colony Helicon Hall in 1906, created to allow both men and women full lives as artists and activists.

Upton Sinclair’s activism spanned half a century, and he wrote book after book in an effort to draw others to his causes. As his son, David, recalled, “My father used to say, I don’t know if anyone will care to examine my heart after I die. But if they do, they will find two words there: social justice.” Because Sinclair was so passionately engaged in the world around him, his story is inextricably linked to the major struggles that gave his life meaning.

Resources

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.