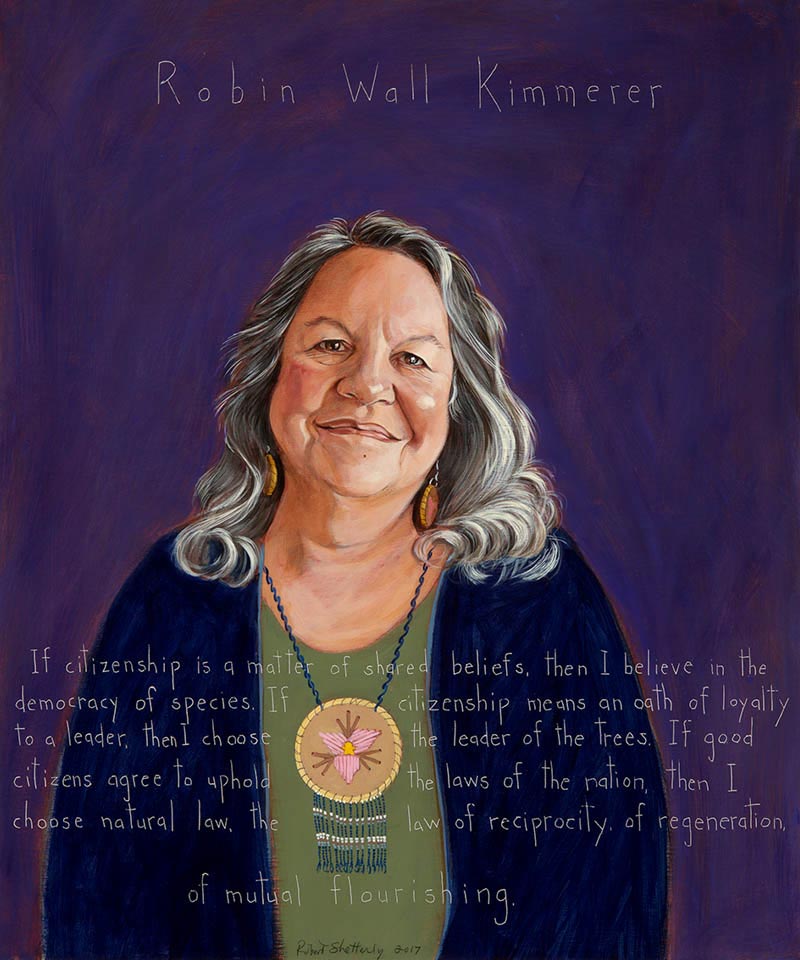

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Biologist, Author : b. 1953

“If citizenship is a matter of shared beliefs, then I believe in the democracy of species. If citizenship means an oath of loyalty to a leader, then I choose the leader of the trees. If good citizens agree to uphold the laws of the nation, then I choose natural law, the law of reciprocity, of regeneration, of mutual flourishing.”

Biography

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, plant ecologist, nature writer, and Distinguished Teaching Professor at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) in Syracuse. She is also founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. Interested in the restoration of ecological communities and the restoration of our relationships to land, she draws on the wisdom of both Indigenous and scientific knowledge to help us reach sustainability goals. For Kimmerer, however, sustainability is not the end goal; it’s merely the first step of returning humans to relationships with creation based in regeneration and reciprocity.

Kimmerer uses her science, writing and activism to support the hunger expressed by so many people for a “belonging in relationship to [the] land” that will sustain us all. She writes, “. . . while expressing gratitude seems innocent enough, it is a revolutionary idea. In a consumer society, contentment is a radical idea. Recognizing abundance rather than scarcity undermines an economy that thrives on creating unmet desires. Gratitude cultivates an ethic of fullness, but the economy needs emptiness.”

Kimmerer is an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, a Native American people originally from the Great Lakes region. Today many Potawatomi live on a reservation in Oklahoma as a result of federal removal policies. In English, her Potawatomi name means “Light Shining through Sky Woman.” While she was growing up in upstate New York, Kimmerer’s family began to rekindle and strengthen their tribal connections. Kimmerer spends her lunch hour at SUNY-ESF eating her packed lunch and improving her Potawatomi language skills through an online class. She is pleased to be “learning a traditional language with the latest technology,” and knows how important it is for the traditional language to continue to be known and used by people. “When a language dies, so much more than words are lost. Language is the dwelling place of ideas that do not exist anywhere else. It is a prism through which to see the world.”

In addition to her academic writing on the ecology of mosses and restoration ecology, she is the author of articles for magazines such as Orion, Sun, and Yes!. Kimmerer also has authored two award-winning books of nature writing that combine science with traditional teachings, her personal experiences in the natural world, and family and tribal relationships. Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (2003) and Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (2013) are collections of linked personal essays about the natural world described by one reviewer as coming “from a place of such abundant passion that one can never quite see the world the same way after having seen it through her eyes.” Jane Goodall praised Kimmerer for showing “. . . how the factual, objective approach of science can be enriched by the ancient knowledge of the indigenous people. It is the way she captures beauty that I love the most. . . .”

Kimmerer has a keen interest in how language shapes our reality and the way we act in and towards the world. In a Yes! magazine article (Spring 2015), she points out how calling the natural world “it” absolves us of moral responsibility and opens the door to exploitation. To stop objectifying nature, Kimmerer suggests we adopt the word “ki,” a new pronoun to refer to any living being, whether human, another animal, a plant, or any part of creation. The plural, she says, would be “kin.” According to Kimmerer, this word could lead us away from western culture’s tendency to promote a distant relationship with the rest of creation based on exploitation toward one that celebrates our relationship to the earth and the family of interdependent beings. She describes this “kinship” poetically: “Wood thrush received the gift of song; it’s his responsibility to say the evening prayer. Maple received the gift of sweet sap and the coupled responsibility to share that gift in feeding the people at a hungry time of year. . . . Our responsibility is to care for the plants and all the land in a way that honors life.”

What is needed to assume this responsibility, she says, is a movement for legal recognition of Rights for Nature modeled after those in countries like Bolivia and Ecuador. This idea extends the concept of democracy beyond humans to a democracy of species with a belief in reciprocity.

An integral part of her life and identity as a mother, scientist, member of a first nation, and writer, is her social activism for environmental causes, Native American issues, democracy and social justice. “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.”

Kimmerer works with the Onondaga Nation and Haudenosaunee people of central New York State and with other Native American groups to support land rights actions and to restore land and water for future generations. She has spoken out publicly for recognition of indigenous science and for environmental justice to stop global climate chaos, including support for the water protectors at Standing Rock who worked to stop the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline (DAPL) from cutting through sovereign territory of the Standing Rock Sioux.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.