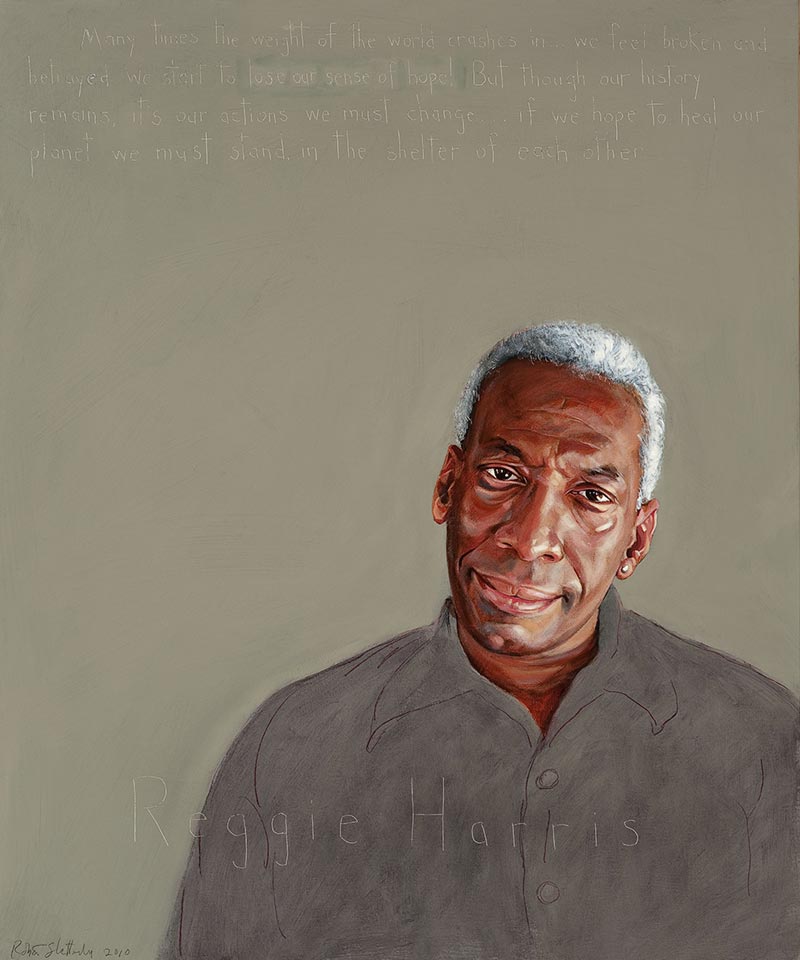

Reggie Harris

Musician, Storyteller : b. 1952

“Many times the weight of the world crashes in… we feel broken and betrayed. We start to lose our sense of hope. But though our history remains, it’s our actions we must change… if we hope to heal our planet we must stand… in the shelter of each other.”

Biography

Born in Philadelphia´s inner city in 1952, Reggie Harris was raised by his mother and grandmother. They lived on little and wore second-hand clothes. But Reggie´s mother and grandmother instilled in the boy the value of treating people with love and respect.

Neither the church he grew up in nor his household was involved actively in the Civil Rights movement. The protests in the south and the 1963 March on Washington were on the news, though. Down the street, The Church of Reverend Leon Sullivan, author of the Sullivan Principles preached the equal treatment of employees regardless of their race both within and outside of the workplace. The young boy saw members of this church working for integration and equality.

Reggie often found himself in situations which were outside his comfort zone. While attending schools away from his neighborhood, he realized that many of the people in his ‘hood’ had little connection to the wealth and power that dominated society. He became intensely aware that blacks were at a disadvantage in the larger world. He also learned that economics and class often transcended racism; some black kids considered him undesirable for dating or socializing because he lived in the projects. To avoid this, Reggie wouldn´t tell people his home address.

He wrote about this time: “I felt very much alone and at odds in my efforts to negotiate the school terrain. When the school had a race riot in my junior year, I realized that I had friends of all races… That was the first time that I began to realize that I was a bridge builder. I also had many incidents in my life…where I found myself betrayed by ‘friends’ and acquaintances who, when push came to shove, decided that our friendship mattered less than not being exposed in their community or families. These were very hurtful episodes that convinced me of the depth and intensity to which racism pervades our society and our relationships.”

Reggie started studying for the ministry in Atlanta, but dropped out. His sense of the world was dramatically reshaped by daily exposure to the realities of segregation and racial inequities in the deep South. Returning to Philadelphia, he took a job working with emotionally challenged children. Through that work he met two men who were Conscientious Objectors against the war in Vietnam. One of them gave him a daily lessons in ‘Life and Politics 101,’ challenging Reggie´s political views and stand up to the injustices he was beginning to see.

While at this job Reggie became consumed by playing the guitar. He took a summer job at a camp outside of Philadelphia where, in 1974, he met Kim Richards.

As their personal relationship deepened at Temple University, they began to sing together at local Philadelphia clubs and coffeehouses. As Reggie says, “It was a relationship that supported two kindred and in some ways battered souls in a healing, inspiring way. Our singing and stage presence had an effect on people beyond just being entertaining. It was as if our hopeful brokenness opened audiences to a greater sense of connection to and discovery of their heritage.”

Kim and Reggie began touring together in 1980 and still average more than 200 yearly appearances. Kim and Reggie deliver positive messages on stages from Italy to Alaska to the Virgin Islands, in classrooms, churches, and auditoriums across America, and on eleven albums and compilations. The show they developed about the Underground Railroad continues to educate people of all ages that “America has a long history of standing together to turn back the forces that oppress and divide.”

Reggie and Kim Harris’ mission is to tell the stories and sing the songs about the legacy of race and racism in the United States and to teach people that they have the spirit, courage and decency to rise above it and heal. Reggie says that through their work they, “… bridge the gaps between those on the left and right…between the unaware and the true believers…between the oppressed and the oppressors and… provide a basis for dialogue and reconciliation.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.