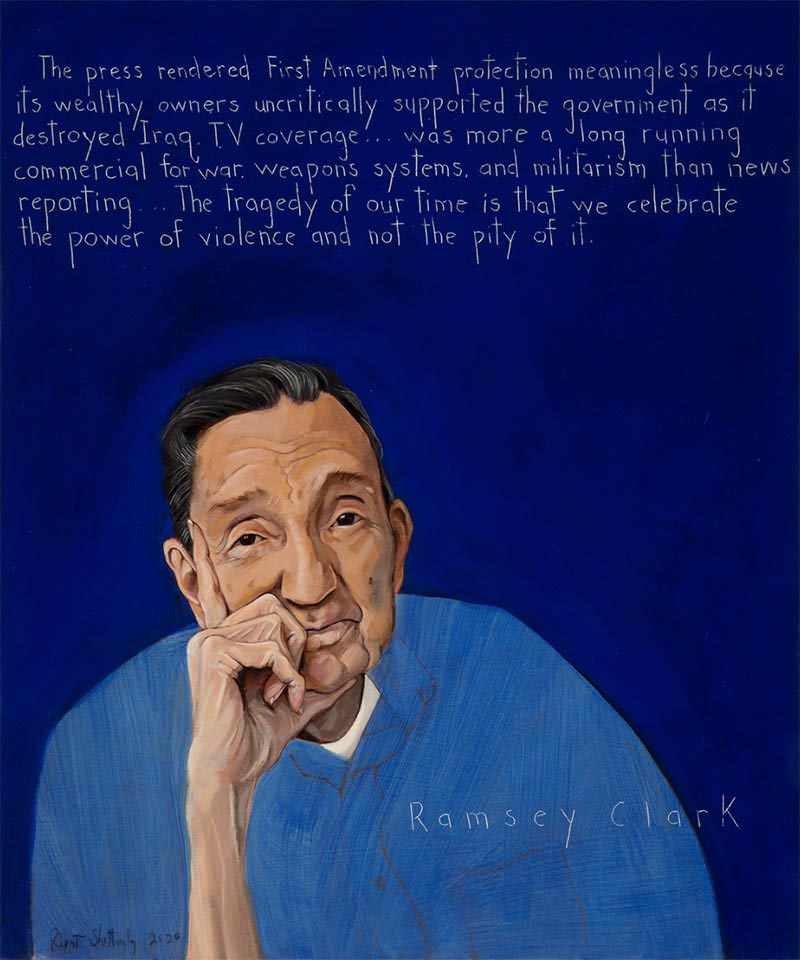

Ramsey Clark

U.S. Attorney General; justice advocate : 1927 - 2021

“The press rendered First Amendment protection meaningless because its wealthy owners uncritically supported the government as it destroyed Iraq. TV coverage…was more a long running commercial for war, weapons systems, and militarism than for news coverage. …The tragedy of our time is that we celebrate the power of violence and not the pity of it.”

Biography

Served in the U.S. Marine Corp (1944-46)

Earned University of Chicago M.A. and law degree

U.S. Deputy Attorney General (1965-67)

U.S. Attorney General (1967-69)

Pro bono lawyer and international activist

Received the Gandhi Peace Award (1992)

Born in Dallas in 1927, Attorney General Ramsey Clark grew up in a family steeped in Texas culture and politics. His father, Tom Clark, taught him the ways of the outdoorsman and the values of the rugged individualist. On weekends they camped, fished, and hunted. Tom’s involvement in local politics had Ramsey attending rallies and speeches, hanging posters, and handing out flyers. Tom Clark’s work as one of the few local attorneys willing to represent African-Americans had a profound impact on his son.

Ramsey witnessed his father’s guilt and despair when one client, a black teenager accused of raping a white woman, was found guilty and sentenced to death. Neither Tom’s legal arguments nor his certainty of the young man’s innocence had been enough to save his life. Another client, Charlie Ellis, hired Tom to save his family’s home, slated by the city for demolition to build a parking lot. They won the case, and the Ellises paid in kind by doing the Clark’s laundry. Every week Ramsey and his mother drove 30 minutes to pick up and drop off their clothes. From his seat in the car, he watched the Ellis children in their dirt yard, laughing and playing, just like he and his cousins did. He sensed something was wrong, though he was too young to understand what it was.

Ramsey’s early career followed expectations. He joined the Marines in 1944 and served as a courier in post-War Europe. He earned three degrees—a bachelor’s, a master’s, and a law degree—in four years. He married his college sweetheart Georgia Welch, fathered two children, and returned to Dallas to become a partner at his uncle’s law firm. On behalf of Safeway Stores, he argued his first case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Tom Clark, appointed to the Court in 1949, recused himself to avoid any appearance of a conflict of interest.

A political outsider in a state that leaned more and more conservative, Ramsey stayed away from Texas politics. At the same time he became bored with corporate law. “I got tired of fighting over other people’s money,” he explained. Then came an opportunity, in the form of John F. Kennedy – the chance to make a difference. In 1961 Ramsey became the Department of Justice’s Assistant Attorney General for Lands. Moving his way up the government ladder, he was appointed Lyndon Johnson’s Attorney General in 1966. His years in public service would change the course of his life.

Early in his tenure, Ramsey focused on managing government lands and spent much of his time procuring property, either through purchase or by force, for the construction of missile sites, space stations, reservoirs, and other public facilities. His attempts to bring fairness to the process – and in particular his efforts to equitably settle lawsuits brought by Native Americans seeking restitution for property seized from their ancestors – caught Attorney General Bobby Kennedy’s attention. As the administration’s focus shifted toward Civil Rights, Bobby Kennedy called on Ramsey to assist.

Hoping Ramsey’s Southern accent and Texas roots would open doors closed to a New Englander, Kennedy sent Clark to Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana to enforce federal integration orders. Ramsey served with a cadre of federal agents who walked the campus of Ole Miss with James Meredith to protect him from violence. In early March of 1965, Ramsey drove back and forth along US Route 80 between Montgomery and Selma, setting up camps for marchers and trying to ensure that armed racists didn’t break the thin blue line protecting civil rights activists. “Imagine,” he later reflected, “in this country, in 1965, having to march five days for the right to vote.”

Ramsey witnessed how these activists pushed government policy by forcing representatives to take stronger action. He noted their patience and commitment and admired their methods of civil disobedience. After leaving office in 1969, he determined to join their ranks, and in 1969, at the age of 41, Attorney General Ramsey Clark began the second stage of his career. He first wrote Crime In America, a book excoriating the correctional system he’d just overseen. In the work he referred to American prisons as “manufacturers of crime” and proposed a systemic overhaul that favored rehabilitation over punishment.

Ramsey then went on a fact-finding trip to North Vietnam. Having been required to tow the administration line and support a policy he had opposed while Attorney General, he could now speak his mind. He returned from his journey an outspoken critic of U.S. intervention overseas.

He took a job with a progressive New York law firm where he focused his energy on pro bono cases, defending anti-war activists, prison rioters, and death row inmates. He joined the board of Amnesty International. He worked with Coretta Scott King to establish a national holiday in honor of her slain husband. He ran for U.S. Senate and lost.

Ramsey’s activism took him overseas to the world’s hot spots, and in 1991 he traveled to Iraq to view the devastation wrought by Operation Desert Storm. He found that “smart” bombs hit more than military targets. They decimated homes, destroyed vital infrastructure, and killed thousands of innocent civilians. He documented violations of international law and war crimes by the U.S. government and witnessed the devastation of sanctions on the people of Iraq. When the second Bush administration made clear its intention to use 9/11 as justification for further aggression against Iraq, Ramsey’s frustration grew.

In 2004, a year after U.S. forces attacked Iraq and captured Saddam Hussein, Ramsey joined the Iraqi leader’s defense team. “[A] fair trial of Hussein will be difficult to ensure—and critically important to the future of democracy in Iraq.” By participating in the tribunal, he hoped to hold it accountable to the laws and spirit of the Geneva Accords and the U.S. Constitution.

Ramsey’s willingness to provide legal advice and representation to those on the outskirts of society and dubbed enemies of the United States brought him both admiration and disdain. To some, he was a voice of truth in a system defined by hypocrisy. Others saw him as anti-American. A man of strong ideals and few words, Ramsey would provide a simple response. “Democracy is not a spectator sport,” he is fond of saying. He believes that for a country to truly be democratic, the people must participate. They must hold their government accountable for its actions. And he spent his life trying to do that.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.