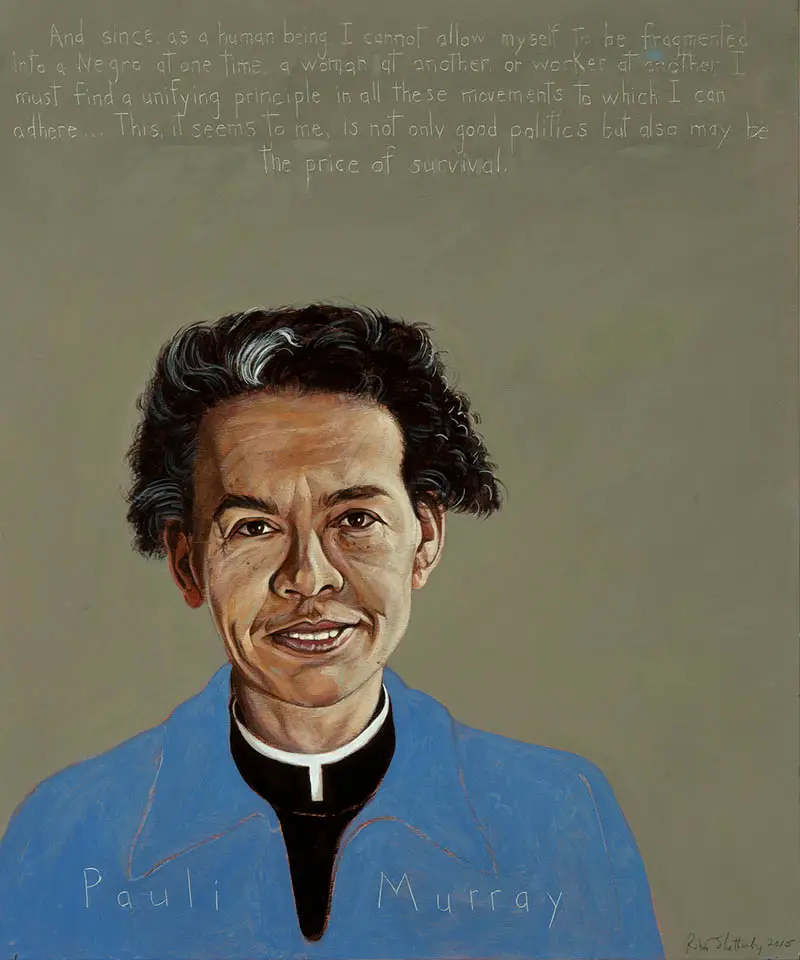

Pauli Murray

Pauli Murray

Attorney, Minister, Author : 1910 - 1985

“And since, as a human being, I cannot allow myself to be fragmented into a Negro at one time, a woman at another, or a worker at another, I must find a unifying principle in all these movements to which I can adhere. … This, it seems to me, is not only good politics but may be the price of survival.”

Biography

“As an American I inherit the magnificent tradition of an endless march toward freedom and toward the dignity of all mankind,” wrote Pauli Murray in 1945. Within every community there are those who refuse to conform to standards imposed on them. Some of these, by sheer force of will, make sure their voices are heard in support of the “march toward freedom.” Activist, writer, attorney and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray demanded to be heard. Yet, in spite of her myriad contributions to the struggle for civil rights for both women and African Americans, Murray has remained, for too long, on the historical periphery.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray was born to William and Agnes (Fitzgerald) Murray in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910. By the time Murray reached adolescence, she had lost both her parents and was raised by her maternal grandparents (Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald) and her maternal aunt (Pauline Fitzgerald Dame) in Durham, North Carolina. After graduating from Hillsdale High School, a historically Black school in Durham, Murray moved to New York City to continue her education and improve her chances of getting into college. Because she was female, she could not attend her first choice, Columbia University (the first women wouldn’t receive diplomas from Columbia’s undergraduate program until 1987). Unable to afford Columbia’s sister school Barnard College, Murray enrolled at Hunter College (which Murray would call “the poor girl’s Radcliffe”), where she earned a bachelor’s degree in English in 1933.

During the Great Depression, Murray worked with both the Women’s Auxiliary of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and with the Works Progress Administration (WPA). She became a member of the peace and justice organization, Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and in 1940, fifteen years prior to Rosa Parks’ protest of Alabama’s bus segregation law, Murray and fellow FOR member Adelene McBean were arrested for refusing to give up their seats on a segregated bus in Petersburg, Virginia. Inspired to study law as a means to address injustice, Murray applied to the University of North Carolina School of Law but was denied admission on the basis of her race. Following in her father’s footsteps, Murray enrolled at Howard University’s law school in 1941, becoming the only woman in her class. At Howard, Murray experienced sexism and coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the discrimination she faced as a woman.

Murray finished first in her class at Howard Law School. Although it was customary for top students to continue their legal studies at Harvard Law School with the assistance of the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship program, Harvard rejected her because of her gender. Undeterred, Murray continued her legal studies at the University of California, Berkeley. After earning an LL.M. degree from Berkeley, Murray was hired as a deputy attorney general for the state of California, another first for an African American, regardless of gender.

In her 1951 book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, Murray offered a definitive framework for challenging state segregation laws. Thurgood Marshall, then the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, cited her book as critical to attorneys working on civil rights cases; it was of particular value to Marshall’s team in preparation for the landmark Brown v Board of Education school desegregation case in 1954..

In 1956, Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, a biographical study of her family in North Carolina. A companion volume, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was more autobiographical and was published posthumously in 1987, two years after Murray’s died.

Murray left the United States to teach law at the University of Ghana in 1960. She returned to the United States to earn a J.S. D. (doctor of juridical science) at Yale University in 1965, the first African American to achieve that degree at Yale. She then taught at Benedict College, a historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina, and, from 1968-1973, at Brandeis University as a professor of American Studies.

As a law student at Howard, Murray had joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and worked directly with future civil rights era luminaries like James Farmer and Bayard Rustin. At the height of the civil rights movement, Murray offered a critique of the 1963 March on Washington (which was organized primarily by her CORE colleague, Bayard Rustin): “It is indefensible to call a national march on Washington and send out a call which contains the name of not a single woman leader.” Murray extended her critique to the broader civil rights movement as a whole: “I have been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grassroots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.”

Murray fully recognized the problem of gender discrimination, not only within the. civil rights movement, but also within society as a whole, noting that “Black women, historically, have been doubly victimized by the twin immoralities of Jim Crow and Jane Crow.” Murray added that “Black women, faced with these dual barriers, have often found that sex bias is more formidable than racial bias.” Due to her work on gender issues, President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. In 1965, Murray co-authored (with Mary Eastwood) an article that appeared in the George Washington Law Review entitled “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII,” which highlighted comparisons between laws that discriminated on the basis of race and those that discriminated on the basis of gender, arguing that the application of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 could be used to combat both forms of discrimination. The following year, Murray became a co-founder of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

After her years at Brandeis University, Murray switched paths and embarked on a new career in the Episcopal Church. Murray began her studies at General Theological Seminary in New York City in 1973 and earned a Master’s degree in Divinity in 1976. The following year, Murray was ordained (at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.) as an Episcopal priest, a first for an African American woman. Murray served primarily in Baltimore, but also in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she died from pancreatic cancer on July 1, 1985.

Murray was a Renaissance woman who deserved greater recognition in her own time. However, it seems true that Murray, who was open about her romantic relationships with women (though she never self-identified as a lesbian) and unapologetic about her non-gender-conforming appearance, was marginalized by the mainstream histories of the civil rights movement, due to her personal preferences and characteristics, something that also happened to Murray’s openly gay contemporary, Bayard Rustin. As the nation’s acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community grows, we are now able to learn more about the full and rich lives lived by members of that community who, like Murray, made important contributions to American history.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.