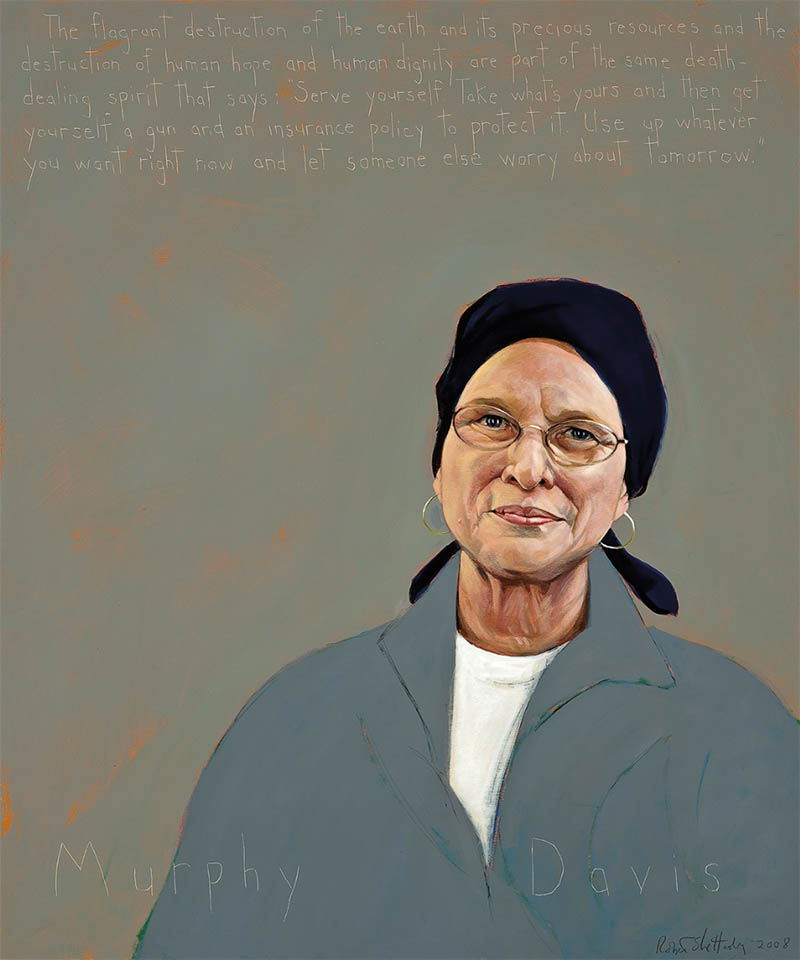

Murphy Davis

Advocate for the Homeless, Activist Against the Death Penalty : b. 1948, d. 2020

“The flagrant destruction of the earth and its precious resources and the destruction of human hope and human dignity are part of the same death-dealing spirit that says: Serve yourself. Take what’s yours and then get yourself a gun and an insurance policy to protect it. Use up whatever you want right now and let someone else worry about tomorrow.”

Biography

Murphy Davis grew up in Louisiana and North Carolina. In 1954, her first year in a New Orleans public school, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their Brown v. Board of Education decision that segregated, “separate but equal” schools were illegal. Even so, it wasn’t until her last year in high school in Greenville, North Carolina, that she attended an integrated school.

Davis attended Mary Baldwin College in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Academically, she found the experience to be rewarding, but struggled to bring her concerns for the poor into a context of wealth and privilege. When she joined the Staunton, Virginia NAACP, she found a place in the Civil Rights Movement and, soon, in the growing opposition to the Vietnam War. Davis’s college professors helped provide an academic context for the justice and anti-war struggle which became the primary motivations in her development as a critical thinker and activist-scholar.

At the Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia in the early 1970s, she joined a small but a growing number of women in the U.S. who were studying theology. Davis was awarded a fellowship to pursue a doctorate in Church History and Women’s Studies but left that track to become a full-time activist when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s capital punishment law in 1976.

Davis, in partnership with her husband, Dr. Eduard Loring – both of whom are Pastors in the Presbyterian Church – made the abolition of the death penalty, creating housing the homeless, the struggles for racial and economic justice, and the abolition of war her life’s work. In 1981, Davis and Loring founded the Open Door Community, a diverse residential Christian community dedicated to changing the economic conditions that create homelessness. Since the center opened in downtown Atlanta, the Loring-Davis family has lived in the community with the homeless, former prisoners, and others who have come to join the struggle to feed the hungry and agitate for justice.

In 1995, Murphy was struck with Burkitt’s lymphoma, a virulent and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. After extensive surgery, the medical team estimated that she had 6 to 18 months to live, under the watchful care of her doctors at Emory University, she lived another five years. Her solidarity with the poor and the condemned only deepened through her experience with cancer.

Murphy published a biography of the civil rights activist Frances Freeborn Pauley in 1996. During her final years, she wrote Surely Goodness and Mercy, a memoir examining America’s health care and end-of-life care systems.

In the midst of what may be seen as grim prospects for the world’s poor, Davis observed, “Our only hope in these days of institutional violence and a seemingly hopeless future for the poor and marginalized is in a relentless practice of sharing, solidarity, resistance, compassion: a revolution rooted in love.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.