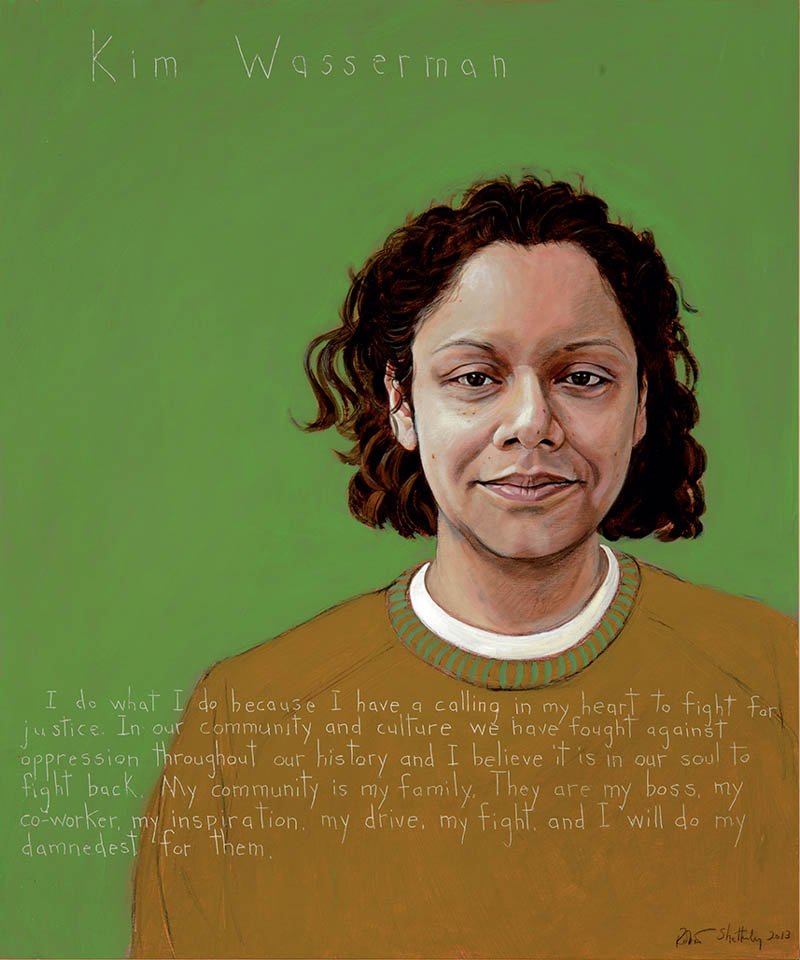

Kim Wasserman

Community Organizer : b. 1977

“I do what I do because I have a calling in my heart to fight for justice. In our community and culture we have fought against oppression throughout our history and I believe it is in our soul to fight back. My community is my family. They are my boss, my co-worker, my inspiration, my drive, my fight, and I will do my damnedest for them.”

Biography

2012: Polluting Fisk and Crawford coal plants are shut down.

2013: Wasserman receives the Goldman Environmental Prize.

In April 2013, Kim Wasserman, a Chicago-based community organizer, was one of six people in the world to receive a $150,000 environmental award. She was the North American recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize for achievement in grassroots environmental activism. Though she was raised by community activist parents, she never aspired to be an activist herself until her young child’s health was affected by pollution.

Wasserman grew up in Little Village, a Chicano neighborhood in Chicago. She and her neighbors lived in the shadow of the Crawford coal plant, which opened in Little Village in 1924. In nearby Pilsen, the Fisk power plant had been burning coal since 1903. Residents didn’t see any danger in the smokestacks, which emitted white plumes that looked like harmless clouds.

In 1998, Wasserman wanted to spend more time with her newborn son, so she took a community organizer job at the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) where she was allowed to bring her baby along as she walked door-to-door getting to know local residents. Then, when he was three months old, Wasserman’s son suffered his first asthma attack. Wasserman soon learned that his asthma was caused by environmental pollution in the neighborhood.

Her job at LVEJO gave her the platform to educate citizens and policymakers about the high rates of asthma, high blood pressure, and bronchitis in Little Village that were caused by the harmful toxins emitted by the Crawford and Fisk plants. Wasserman continued walking the neighborhood, explaining to residents that they had the power and the right to fight for cleaner air.

Then in 2002, a Harvard School of Public Health released a study that attributed 41 premature deaths and 2,800 asthma attacks each year to the two plants. These findings energized the community, giving them the hard data they needed to support their fight for clean air. Even when confronted by the scientific data, however, Mayor Richard Daley continued to ignore their efforts.

After years of hard work and leadership in the fight against the coal plants, Wasserman was promoted to coordinator of LVEJO, overseeing all of the agency’s projects. Despite having additional responsibilities at LVEJO, she kept working to close the power plants. The campaign did not have a lot of money to spend, but made the most of their ability to speak up in creative ways. They lead “Toxic Tours” of industrial sites and hosted the “Coal Olympics” when Chicago made its bid for the 2016 Olympics. At the Coal Olympics, youth participants jumped over cardboard models of coal plants and mountains destroyed by mining. Despite these protests, local officials continued to protect the coal industry.

In 2010, the EPA found that the two power plants were among Illinois’s leading sources of toxins, including barium compounds, hydrochloric acid, hydrogen fluoride, mercury compounds and sulfuric acid. In response, Chicago activists came together to form a Clean Power Coalition. When Rahm Emanuel was elected mayor along with several new City Council members, Wasserman and LVEJO made their case again. The city finally enacted strong pollution controls that required the plants to make expensive changes to their infrastructures. As a result, the plant owners decided to shut down.

In her work as coordinator of LVEJO, Wasserman prioritizes the voices of local residents. As she organized to close the Crawford and Fisk plants, Wasserman built an inclusive coalition of national and local faith, health, labor, and environmental groups, but most importantly, the voices of Little Village residents were always present. It took twelve years, but Wasserman never gave up.

She’d applied an important lesson she learned during her youth: “When I was in sixth grade I organized a sit-in at our local grammar school. They were hiring a new principal and the student council wasn’t getting a seat at the table. I thought that was wrong so I organized our school to protest. As a very young child I had parents who taught me if something is wrong, speak up. People are very open to doing the right thing. It’s just a question of working with them.”

Wasserman and LVEJO continue to address environmental devastation in Little Village, building their case for clean drinking water and adequate storm sewers, among other community improvements.

________________________________________________

Sources:

Chicago Magazine, “2011 Green Awards: Kimberly Wasserman,” by Jennifer Wehunt. April 2011.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.