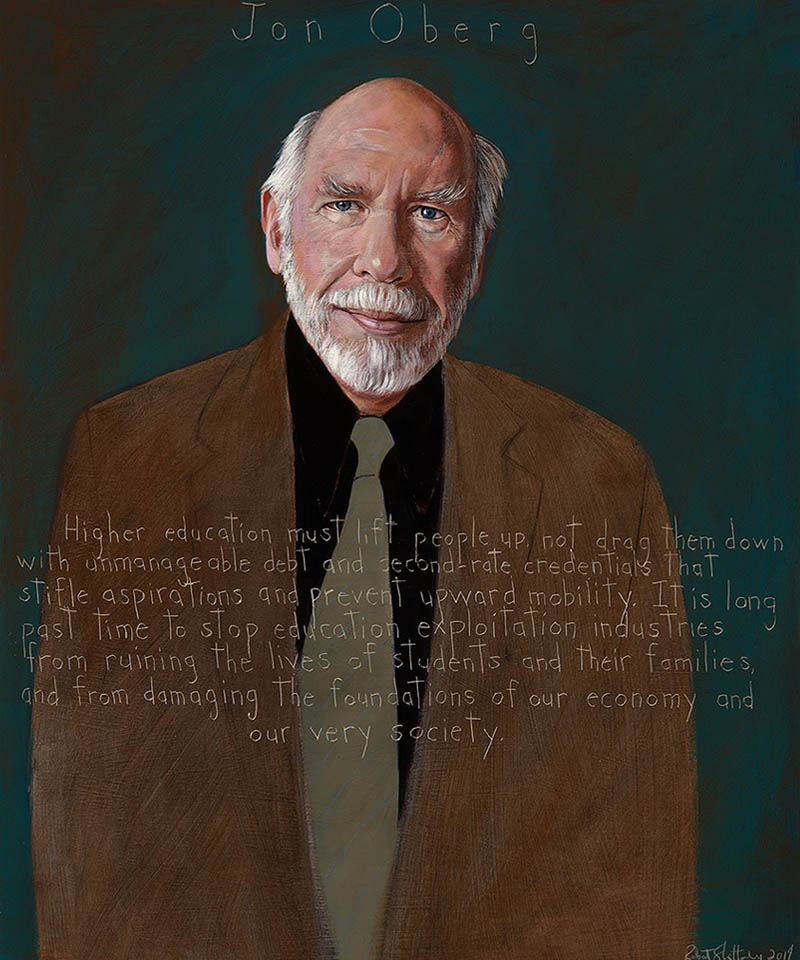

Jon Oberg

Public Servant, Whistleblower : b. 1943

“Higher education must lift people up not drag them down with unmanageable debt and second rate credentials that stifle aspirations and prevent upward mobility. It is long past time to stop education exploitation industries from ruining the lives of students and their families, and from damaging the foundations of our economy and our very society.”

Biography

Jon Oberg was born 1943 and grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska. A third generation Swedish-American, he has retained a strong tie to his home state throughout his long career as a public servant, which includes experience at all levels of government (local, state, and federal) and in each of the three branches (executive, legislative, and judicial).

Oberg studied at the University of Nebraska and in Europe, earning degrees in psychology and political science and developing expertise in the areas of public budgeting and finance. He has served his country as a naval officer, as a civil servant for the State of Nebraska, as staff to Congress, and as Congressional liaison for the U.S. Department of Education. Being a public servant and working for the government in a democracy meant to Jon that he should give taxpayers their money’s worth. “Public service,” he says, “required that the overall good must be placed ahead of any political, factional, or special interest considerations, including my own personal interests. Good government isn’t easy; it requires sacrifice from those within, and cognizance if not appreciation from those in whose name it is carried out.”

Early in his career, Jon was troubled when he read a scholarly paper that concluded that our country’s unstated social policy was “higher education for the rich, welfare for the poor.” He would work for four decades to make that conclusion incorrect, ultimately taking action to end fraudulent practices in the student loan industry by lenders who were paid through the U.S. Department of Education. His whistleblowing — Oberg brought systemic abuses to the attention of his supervisors and to Congress, and pressed lawsuits on behalf of the American people under the False Claims Act to recover taxpayer monies — has helped to expose the commercialization of higher education and the ways that social policies reinforce the gap between rich and poor.

In 2001, Oberg took a position in the Institute of Education Sciences at the U.S. Department of Education. As he was conducting research on federal grants, he discovered a piece of information that puzzled him: Why were billions of seemingly excessive taxpayer dollars being paid by the DoE to certain lenders? His research skills enabled him to ferret out suspicious details about how student loan providers were doing business with the federal government. He asked his supervisor if he could delve into the records and explore why an interest rate of 9.5%, guaranteed in the 1980s, was still being paid to lenders after the obligation and financial need to do so had ended.

Oberg’s boss denied his request and rewrote his job description to make sure this research wouldn’t be considered part of his job. But Jon found alternative ways to continue his investigation. Checking with the ethics department at the DoE to make sure what he was doing was legal, he used his own resources and, on his own time, read all the available documentation he could find on the loopholes being exploited by lenders.

He then turned over the information he dug up to Congress. Over the next four years, the DoE and Congress made efforts to end the abuses that had allowed about a dozen lenders to bilk taxpayers of what was estimated to be billions of dollars. The Department reached settlements with a few of the lenders to pay back a fraction of the amounts they illegally billed and were paid in exchange for their agreeing not to try to collect further illegal payments. As the original source who had discovered the illegal claims, Jon filed suit under the False Claims Act. The False Claims Act is a statute that allows original sources of information about fraud perpetrated by corporations against the government to file suit. (If successful, the persons who relate the information can recover up to a third of the amount of the fraud owed back to the government.)

Luckily for everyday Americans, Jon was not done with his civic work. Retiring from his government job in 2005, he proceeded to press lawsuits on behalf of the federal government against lenders who had defrauded taxpayers with the false subsidy claims. He has won several of the cases to date; millions have been returned to the public coffers and he has used a significant share of the monies awarded to him by the U.S. Justice Department to support college students in need and to help make further reforms by advising on how to close the loopholes that the lenders had been exploiting for years without challenge.

Not only did Oberg ultimately succeed in stopping lenders from gaining huge, illegal profits at the expense of taxpayers, he demonstrated how growth of the student loan industry has been negatively affecting American society on a broad scale. Says Oberg, “The result is a huge amount of student loan debt that hangs over the entire economy and too many personal futures that are ruined, only because financially needy students sought to better themselves through higher education. No wicked social engineer could have devised a better way to hurt students, families, and the U.S. economy.”

In a democracy, we depend on the ability of educated American citizens to make informed decisions and to be civically engaged, as well as to make contributions to the workforce and economic system. Instead of treating education as a social benefit, it has been turned into a huge business in the United States. A majority of students (and their families) now leave college with student loan debt that severely narrows their career choices and impacts the rest of their lives.

Like many whistleblowers who have taken risks to stop fraud and abuse, Oberg thinks of himself not so much a whistleblower but as someone simply trying to do his job conscientiously.

While he lives most of the time in Maryland and continues his civic engagement in issues of higher education, Oberg continues to maintain a home on native and restored prairie in Nebraska and to study the work of American naturalists.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.