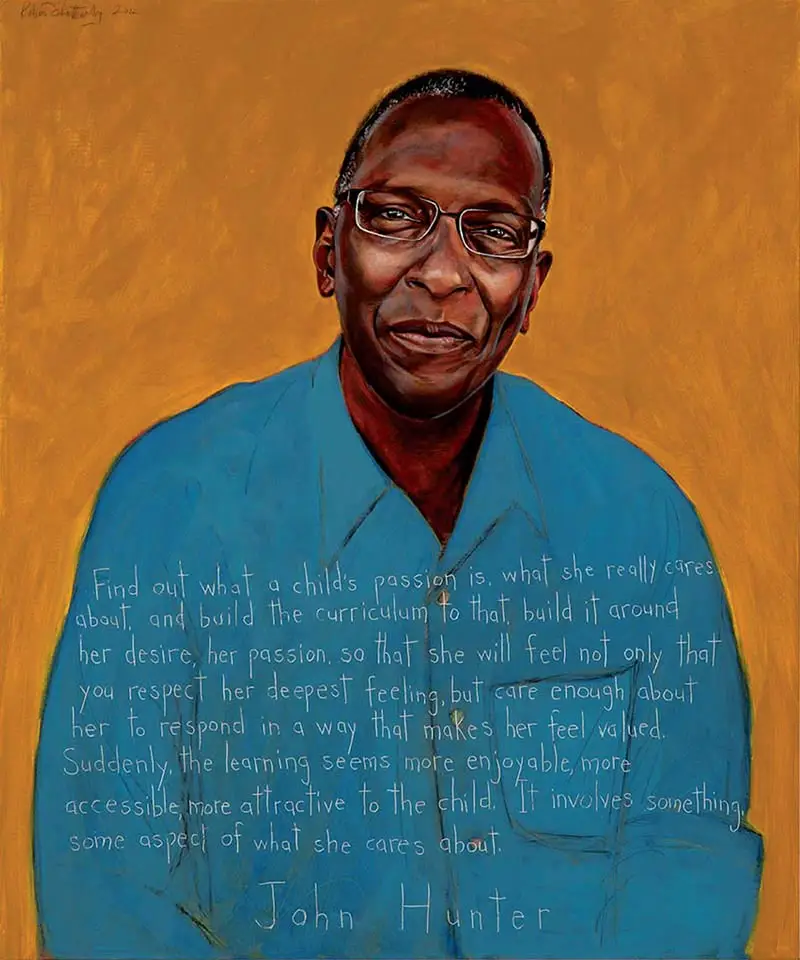

John Hunter

John Hunter

Educator, Musician, World Peace Game inventor : b. 1954

“Find out what a child’s passion is, what she really cares about, and build the curriculum to that, build it around her desire, her passion, so that she will feel not only that you respect her deepest feeling, but care enough to respond in a way that makes her feel valued. Suddenly, the learning seems more enjoyable, more accessible, more attractive to the child. It involves something, some aspect of what she cares about.”

Speaking Truth to Youth

Educator John Hunter and his former student Choetsow Tenzin, a sophomore at Harvard, encourage us to see each new person with fresh eyes and to live by Hunter’s motto, “Someone has to do it.”

Biography

Education visionary and fourth-grade public school teacher John Hunter is optimistic about the fate of the world, despite its seemingly intractable problems. His positive attitude comes from decades of watching nine- and ten-year-olds solve the toughest global problems he can throw at them in an open-ended political science simulation he calls the World Peace Game.

In the game, Hunter’s students spend eight weeks grappling with fifty complex, interlocking crises (famine, war, colossal debt, refugees, wealth disparity, climate change, etc.), and every year “they collectively decide to save the world,” he says. They also save it in a different way every year, using new solutions each time. “They find infinite ways to do good—from the infinite gardens of their mind. . . . There are as many good solutions as there are children in the world,” says Hunter.

Hunter first created the game in 1978 at an urban high school in Richmond, Virginia, where he had landed his first teaching job. “We were studying Africa, so I thought, ‘Why not put it on a game board?’ So I took the continent of Africa, divided it into countries, divided the kids into teams, and said, ‘Now what should we do with the continent? Well, there are a lot of great things, but let’s look at the problems and fix them. Let’s solve things.’”

The game evolved into an elaborate, four-tiered plexiglass structure that dominated the center of his classroom at Agnor-Hurt Elementary School in Charlottesville, Virginia. Hunter outlined the crises, appointed only a few key players—such as the “prime ministers” of each made-up country—and then stepped aside. Nearly everything that followed came from the students themselves.

The game is deliberately designed so students “fail massively at first, but we create a safe environment, with great care and love, where it’s okay to fail and learn from that,” he says. The 30-player, 50-problem nature of the World Peace Game is so complex “it immediately plunges students into uncertainty,” and as play progresses, “the rules and situations change, with multiple consequences, most of them hidden,” says its inventor.

At first glance, it looks like a competition between different teams, but “about halfway through, they have a sudden realization that they are on the same side. Everything is interrelated. To win, they have to go into a hyper-collaborative state.” In order for anyone to win, says Hunter, “everyone has to win.” Not only do they negotiate peace, but each country has to wind up with an improved economy as well.

Each session begins with a reading from Sun Tzu´s “The Art of War,” which encourages students to think about the many ways armed conflict can be avoided and then apply the ancient text to modern day crises.

Solving problems in the game “is certainly a messy process, with false starts, inaccurate assessments, and wrong-headed impulses,” he admits, “but the thought of there being no way out does not seem to occur to children. . . . They are working from a place before perspectives harden and attitudes solidify—where, for example, compromise is demonstrated to be a lack of separateness from others, rather than being seen as personal sacrifice.”

Hunter´s encouragement of problem solving, cooperation, and higher-order thinking has earned recognition for him and his students. They’re the subjects of a documentary film called “World Peace and Other Fourth Grade Achievements” and also of Hunter´s celebrated 2011 TED Talk. In 2012, Hunter and his students were invited to explain their strategies to U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta and his staff at the Pentagon. In 2013, his book World Peace and Other Fourth Grade Achievements was published. “Teachers are writing us from all over the world. They watch the film and are inspired to do it themselves. They’re creating versions of ‘World Peace’ in Hong Kong, Indonesia and India. We’re just humbled. It’s a joyous ride,” says Hunter.

Hunter never expected to follow in the footsteps of his mother, who was a teacher. He dropped out of college to travel, studying philosophy and religion on his own as he made his way through India and the Far East. Once home, his mother exhorted him to finish school, so he signed up for the only thing that intrigued him—an experimental teaching program. The idea of trying a new approach to education was somewhat familiar to him, having been selected as a child to participate in a Civil Rights-era effort to integrate an all-white school in Richmond. But he credits his success in teaching in part to his first boss, a woman who he says gave him the freedom to find his own way as a educator.

And Hunter insists that he is as guided by his students as they are by him: “I see everyday how my own understanding and knowledge is dwarfed by the collective and collaborative problem solving of young minds that aren’t fixed on ideologies, philosophies, perspectives and perceptions about life. . . . I see children not as unfinished adults but as people, unique individuals. I treat them almost as colleagues, peers. I tell them, you have one teacher, but I have 30.”

Hunter has set up the World Peace Game Foundation to train facilitators around the world, bringing his award-winning curriculum to schools everywhere. “The WPG is not a permanent system, but rather a temporary, internalized, flexible and renewable practice,” says Hunter.

Despite its wild success and growth, the game’s fundamental principles remain: Allow students the luxury of failure, encourage them not to be afraid of complexity, and help them develop empathy and compassion. “The World Peace Game,” Hunter says, “is about learning to live and work comfortably in the unknown.”

Hunter graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond and lives in Charlottesville with his wife Leslie and daughter, Madeline. Music is an important part of his life; Hunter has been both a studio musician and a live performer with the Ululating Mummies, an avant-garde/world music band based in Richmond.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.