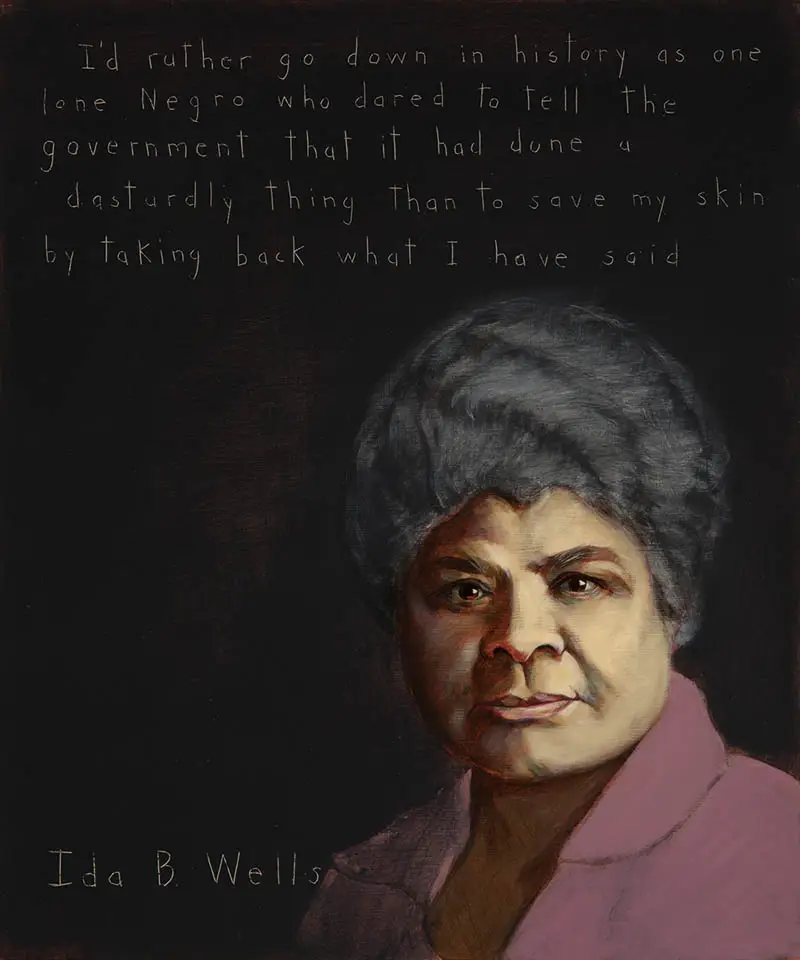

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells

Journalist, Anti-Lynching Crusader, Women’s Rights Advocate : 1862 - 1931

“I’d rather go down in history as one lone Negro who dared to tell the government that it had done a dastardly thing than to save my skin by taking back what I have said.”

Biography

Was born into slavery three years before the end of the Civil War.

An investigative journalist who wrote against lynchings in the South and was active in the Anti-Lynching movement.

A cofounder of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

A co-founder of the National Afro-American Council and the NAACP.

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi, just months prior to emancipation in 1863. Her parents died of yellow fever when she was sixteen, and Wells, though minimally educated, began teaching to support her five younger siblings. She somehow managed to keep her family together, attend Rust University (now Rust College), and secure a teaching position in Memphis in 1888.

When she was twenty-one, traveling in Tennessee, Wells defied a conductor’s order to move to a segregated railroad car and was forcibly removed. She won a lawsuit against the railroad (which was later reversed) and, from that point on, worked tirelessly to overcome injustices to people of color and to women. In 1889, she became co-owner of a Memphis newspaper, the Free Speech and Headlight. Her editorials protesting the lynching of three Black friends led to a boycott of white businesses, the destruction of her newspaper office, and threats against her life. Undeterred, she carried her anti-lynching crusade to Chicago and published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892), documenting racial lynching in America.

In 1895, when she married Ferdinand L. Barnett, attorney and owner of The Conservator, Chicago’s first Black newspaper, she hyphenated her name, making it Wells-Barnett. Though married and eventually the mother of four children, Wells-Barnett continued to write and organize. She was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), marched in the parade for universal suffrage in Washington, D.C. (1913), and established the Negro Fellowship League for Black men and the first kindergarten for Black children in Chicago.

Wells did not succeed in her crusade to get Congress to pass anti-lynching laws during her lifetime, but her efforts as a writer and activist dedicated to justice and social change established her as one of the most forceful and remarkable women of her time. Ida B. Wells died in Chicago on March 25, 1931. She once said, “One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.