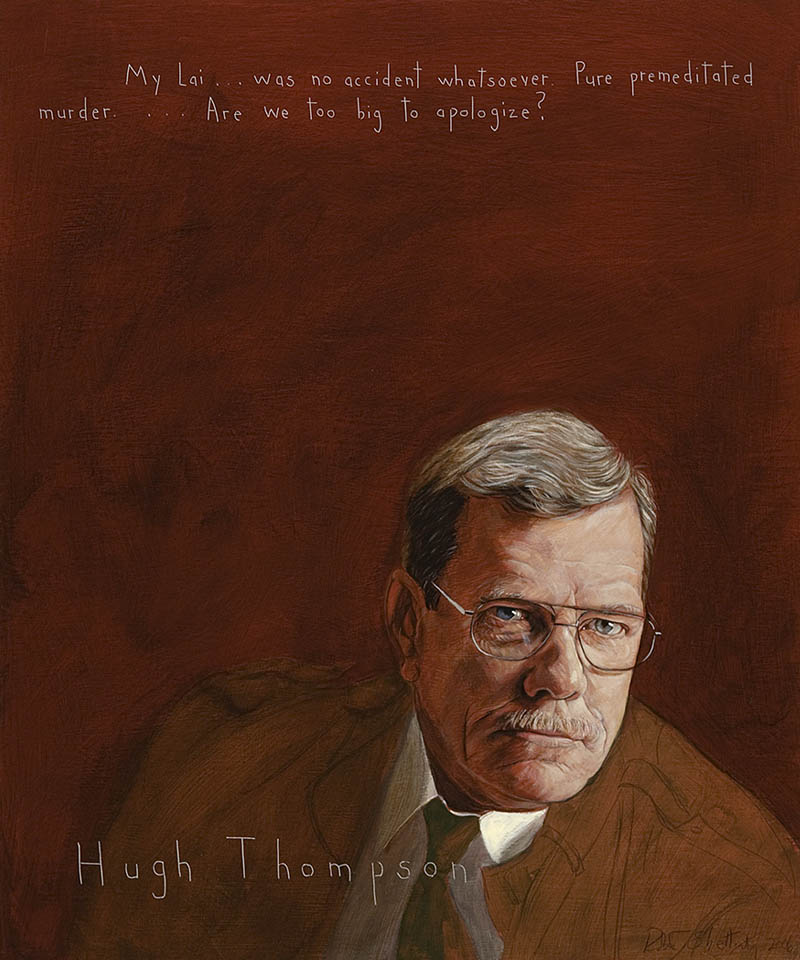

Hugh Thompson Jr.

Helicopter Pilot : 1943–2006

“My Lai…was no accident whatsoever. Pure, premeditated murder. Are we too big to apologize?”

Biography

On the morning of March 16, 1968, Chief Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson was flying reconnaissance over “Pinkville,” where intelligence said Viet Cong were hiding. While he drew no fire to indicate that the enemy was present, each pass made Thompson more aware that something was terribly wrong on the ground.

Today Pinkville’s Vietnamese name, My Lai, is synonymous with tragedy and American shame. When Thompson realized that U.S. soldiers were slaughtering civilians that day, he blocked them with his helicopter, had his crew train machine guns on the American troops, and rescued a group of villagers hiding in a bunker. He landed again when he saw motion in a drainage ditch full of bodies, and crew chief Glenn Andreotta waded in to rescue a young boy who was unhurt but covered with the blood of others. Thompson then reported the My Lai massacre to his Army officers, leading to a cease-fire order. An elaborate cover-up ensued.

Thompson remained in combat until he was shot down for the fifth time and broke his back, and then he returned to the States to train helicopter pilots. Later, he flew for oil companies and eventually worked for the Louisiana Department of Veteran Affairs, speaking widely about his experience at My Lai.

By the time the Pentagon began a high-level inquiry, Thompson had managed to put the horrific day out of mind. Like his father, he had served in the U.S. Navy as well as the Army, and he condemned neither the military nor the war. Still, he was surprised and bitter when he was reviled for his role at My Lai. L. Mendal Rivers, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, claimed that Thompson was the only guilty one there, since he had threatened to shoot American troops.

Thompson threw away the Distinguished Flying Cross he was awarded for saving the lives of Vietnamese civilians “in the face of hostile enemy fire.” The citation didn’t mention that the hostile fire was from the American side, and Thompson felt his commanding officers were trying to buy his silence.

In 1998, a nine-year letter-writing campaign started by a university professor finally brought Thompson the Soldier’s Medal for heroism not involving conflict with an enemy. He refused to accept the award unless it was given also to his door gunner, Lawrence Colburn, and posthumously to Andreotta, who was killed in a crash three weeks after My Lai.

Ten days after receiving the Soldier’s Medal at the Vietnam Memorial, Thompson and Colburn attended a service at My Lai marking the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre. Thompson was stunned when a Vietnamese woman wished aloud that those who had shot at them had attended so that they could forgive them—something he said he could never do.

Later that year, Thompson said Americans need to select leaders very carefully. “We need some negotiators first and fighters second,” he told CNN.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.