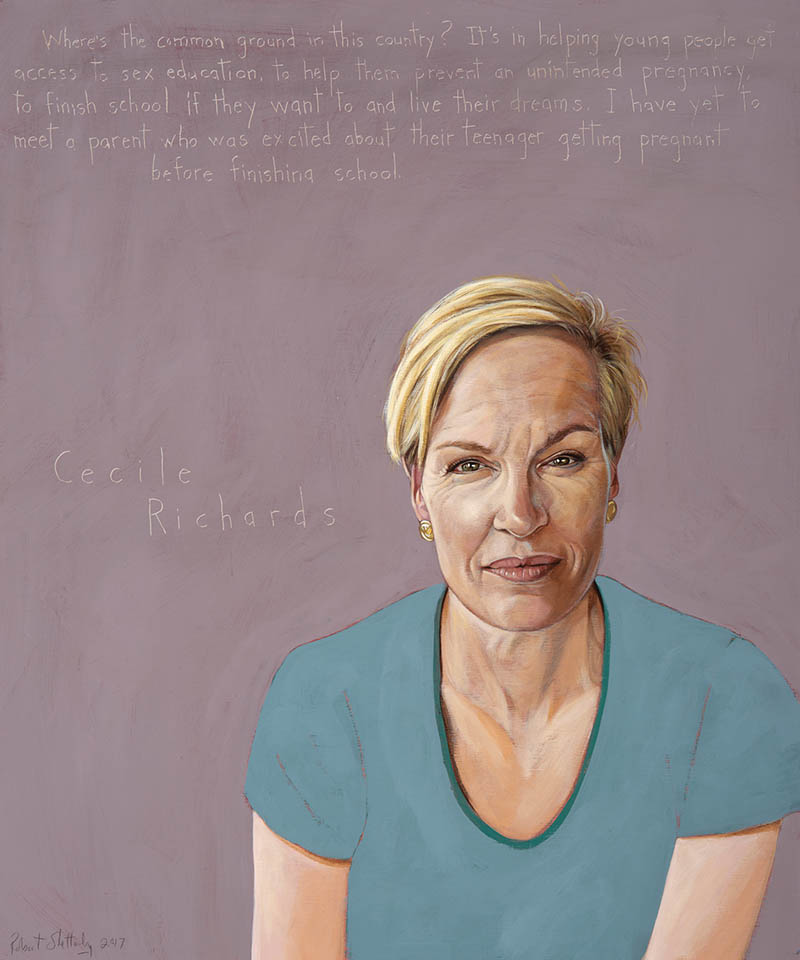

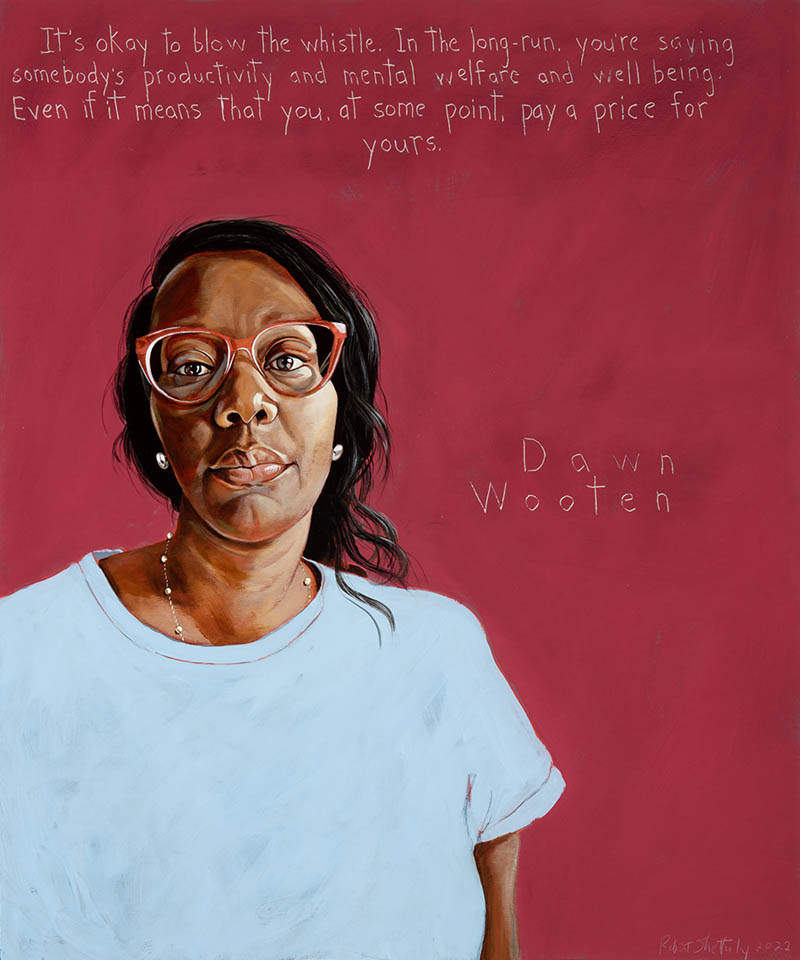

Dawn Wooten

Whistleblower, Nurse, Human Rights Advocate: b. 1978

“It’s okay to blow the whistle. In the long-run, you’re saving somebody’s productivity and mental welfare and well being. Even if it means that you, at some point, pay a price for yours. “

Biography

Whistleblower at Georgia’s Irwin County Detention Center

Recipient of a 2022 HMH Foundation First Amendment Award

Dawn Wooten knew that what she was seeing was wrong. In the early spring of 2020, as the deadly coronavirus sent the world into lockdown, the management team at her place of employment—the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia—seemed intent on ignoring the threat. The facility’s leadership failed to warn staff and detainees when the first cases came to the facility. Medical complaints were ignored. Management refused to test those with symptoms. Wooten, whose sickle cell anemia put her at high risk, learned after the fact that she had been asked to treat detainees who had tested positive for the virus. The approach went against Wooten’s training as a nurse and defied her values as a human being. People were dying in the thousands. It was imperative the pandemic be taken seriously.

A single mother of five, Wooten faced a difficult decision. She could opt to stay at her job and provide the best care possible under the circumstances. This approach would allow her to quietly continue advocating for patients and keep her family clothed and fed. Yet it put her health and the health of her children at risk. Wooten thought of her grandmother, who raised Dawn and her five siblings in a segregated community outside of Tifton, Georgia. Her grandmother gave everything to her children and grandchildren, often sacrificing her own well-being. Dawn remembered her uncles coming for dinner, eating their fill, and watching her grandmother make her own meal from their scraps. It wasn’t right, so Dawn worked odd jobs, picking crops at nearby farms and ironing the shirts and pants of wealthier neighbors, to supplement her grandmother’s fixed income. If she could help it, no one would be exploited because of their circumstances. Wooten approached the leadership team at Irwin with her concerns. Nothing changed. She continued to advocate for better treatment of detainees and more protection for employees. The mismanagement continued.

Wooten pushed harder and her reputation as someone willing to challenge the status quo grew. Detainees came to her revealing stories that involved other forms of medical abuse. More than forty women living at the center claimed to have been subjected to invasive, non-consensual gynecological surgery. A Jamaican immigrant, told she needed surgery for cysts in her stomach, later discovered physicians had removed one of her fallopian tubes. “What happened to me at Irwin is not a one-off aberration,” she said. “[I]t’s a legacy of American white-supremacist pseudo-science going back decades…a consequence of a cultural through-line of racism and anti-immigrant fervor, reinforced by systemic inequities and bias.” Her peers reported receiving hysterectomies without consent. Other detainees had their ovaries removed.

Dawn had grown up helping others defend themselves. Her innate sense of justice had prompted her to take action whenever she had seen mistreatment. She’d jump in without thinking, verbally defending classmates at school who were bullied. When words didn’t work, she’d protected her peers in other ways, often coming home scuffled from a fight. Dawn’s grandmother had encouraged her to keep her head down and her mouth closed: “that thing under your nose is going to write more checks than your ass can cash,” But that approach went against Dawn’s strong sense of justice. She couldn’t look away then. Nor could she look away now. She listened to the women’s stories and reported the violations to her managers.

In twelve years of nursing, Wooten had never been remanded for poor performance or for violating company protocols. “The moment I realized I was being retaliated [against was] when I was written up…I automatically knew that they were building a case.” Wooten had been out sick and had submitted a doctor’s note explaining her absence. Her supervisor reported her as a “no call, no show.” The deputy warden shrugged it off. “Dawn, just take it. It’s just a write up,” he said. Soon afterwards, Wooten was demoted from full-time employee to an on-call position.

Around this time, allegations against LaSalle Corrections, the private corporation operating Irwin, began to surface from their other facilities. Employees in one Louisiana center submitted an anonymous letter to Congress alleging gross mismanagement of the pandemic. They outlined a system that failed to isolate victims of COVID-19, exposing healthy staff members and detainees to the deadly virus. Dorms and common areas were not properly sanitized. Management failed to provide proper equipment and refused to acknowledge the death of two employees.

Wooten had exhausted communications with the leadership at Irwin. She mourned with the women who would never be able to experience the joy of childbearing. She could no longer watch as their lives and the lives of others were placed at risk. On September 8, 2020, with the assistance of attorneys from the Government Accountability Project, she submitted a complaint to the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General alleging a lack of medical care, unsafe work practices, and the absence of adequate protection for detained immigrants and employees at the Irwin County Detention Center. Less than a week later, the legal advocacy group Project South submitted a second complaint on Wooten’s behalf, again outlining neglect and abuse in the delivery of medical care at Irwin.

Wooten’s act of courage caught the attention of the United States Congress, and more than 170 representatives demanded an investigation. Her perseverance inspired 57 survivors of unwanted medical surgeries to sue the corrections facility. All detained immigrants have since been moved out of Irwin. ICE severed its contract with LaSalle. Rachel Maddow and Chris Hayes invited Wooten for interviews on their shows. Dawn Wooten saved lives and the emotional well-being of many victims. Still, the scars are deep, and many cases remain unresolved.

Dawn Wooten didn’t set out to be a hero. She simply wanted to see people treated humanely. Like many whistleblowers, she is paying a high price for her integrity. Since revealing the malpractice at Irwin, and despite a national shortage of nurses, she has been unable to find full-time employment. She remains “on call” with LaSalle but is not offered shifts. Local resentment in a community dependent on the detention center for employment looms over her family. Wooten received a call from a stranger who threatened to kidnap her children. Her son suspected he and his siblings were being watched after noticing an occupied vehicle repeatedly parked across the street from their school. The threats became serious enough that she and her children were given security guards. Their moves from hotel to hotel, living in lockdown, led to isolation and depression. In protecting others, Wooten made herself vulnerable. Her decision has brought immeasurable hardship to her and her five children.

Wooten wonders: if she’d known the consequences of exposing her employer’s illegal practices, would she have done it? While her efforts have brought notice to the plight of immigrants in the United States and garnered significant reform, she has been vilified and has put her children at risk. But as one of the many Americans determined to see human rights as the driving force behind our nation’s legal system and its immigration and asylum policies, she couldn’t keep quiet. Given the opportunity, she would again choose justice over fear.

-authored by Julie Gronlund

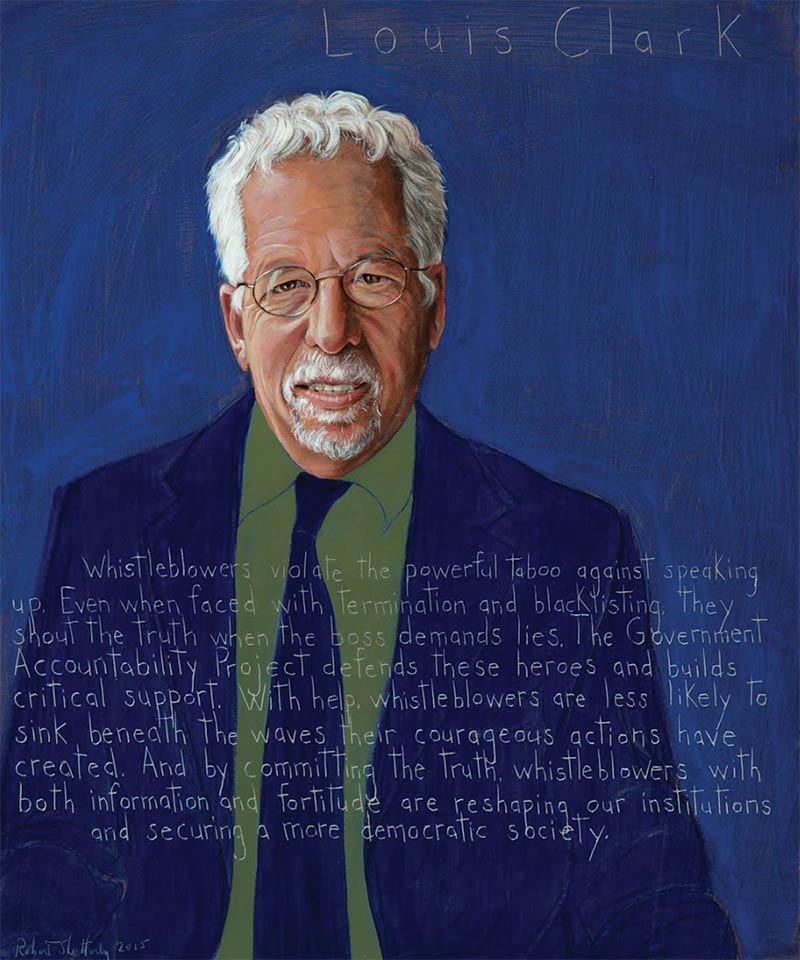

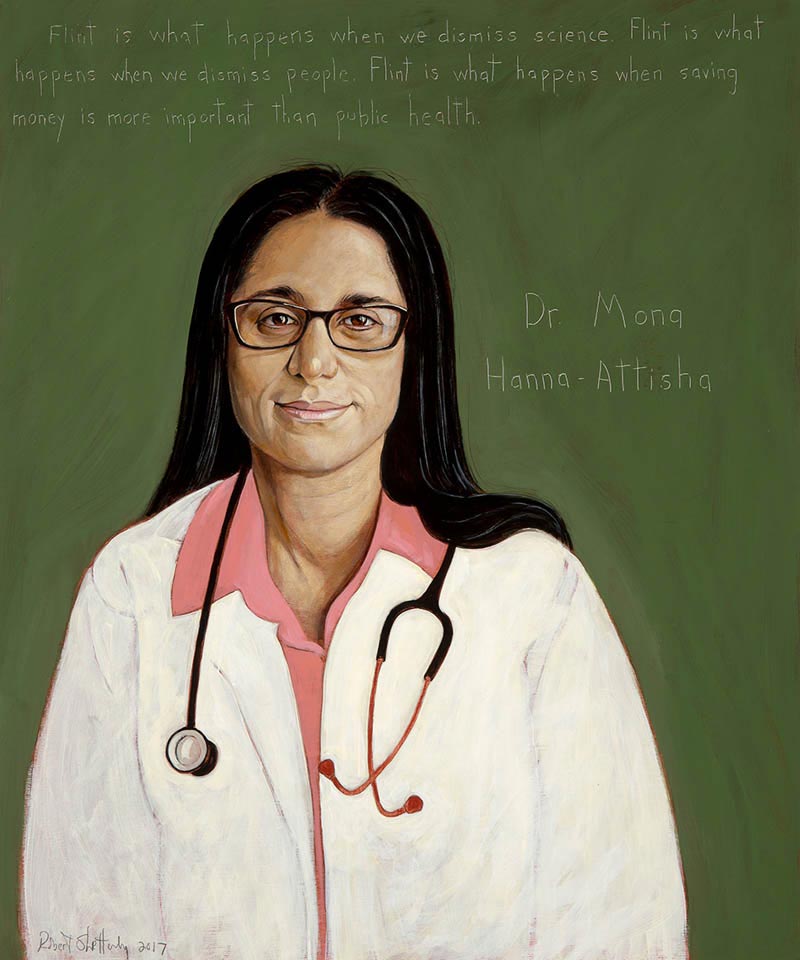

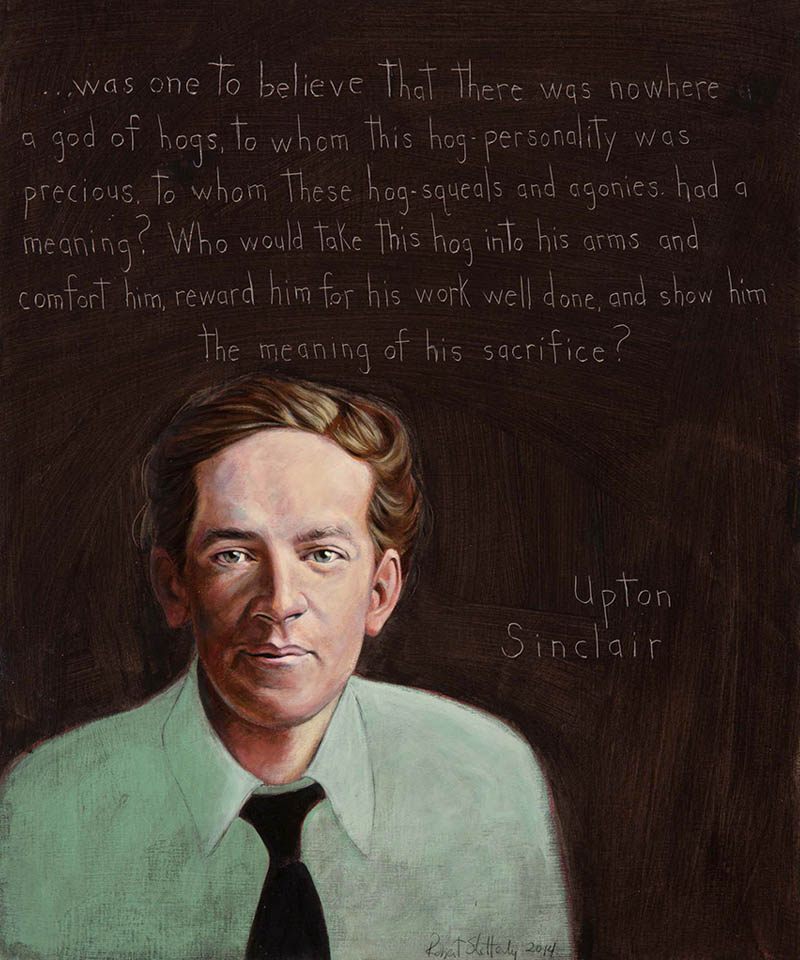

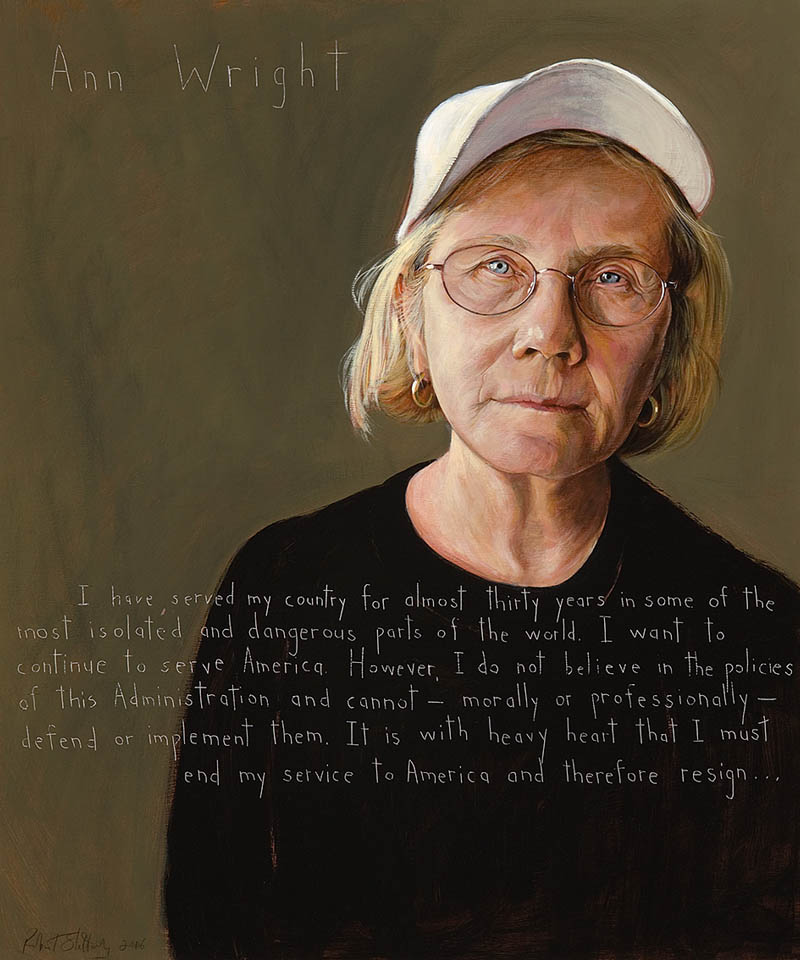

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.