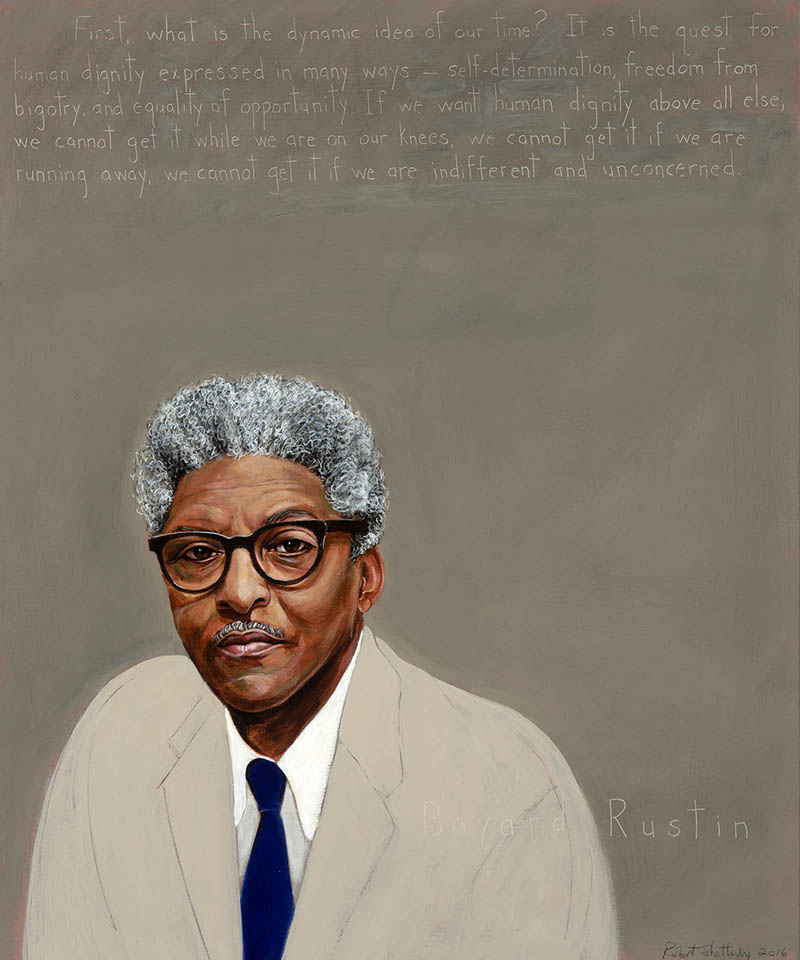

Bayard Rustin

Organizer, Activist : 1912 - 1987

“First, what is the dynamic idea of our time? It is the quest for human dignity expressed in many ways – self determination, freedom from bigotry, and equality of opportunity. If we want human dignity above all else, we cannot get it while we are on our knees, we cannot get it if we are running away, we cannot get it if we are indifferent and unconcerned.”

Biography

Bayard Rustin was at the forefront of almost every progressive movement of the twentieth century. Yet it’s possible that you have never heard of him. One of the most successful organizers of his time, working for peace, labor, and civil rights, he organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Rustin traveled the globe, advocating for democracy and human rights wherever he touched down: “When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.” Though his legacy garners more attention all the time, his brilliant contributions were often erased due to the fact that he lived his life as an openly gay man in an era when same-sex orienation was considered a perversion.

Bayard Taylor Rustin was born March 17, 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania to Florence Rustin and Archie Hopkins, but he was raised by his maternal grandparents, Janifer and Julia Rustin. Julia Rustin, an active member of the NAACP, and a Quaker, imparted the values to her grandson that would guide him for the rest of his life. He attended an integrated high school where he was a star athlete, amazed people with his beautiful singing voice, and was at the top of his class intellectually.

Following high school, Rustin attended the historically Black Wilberforce University in Ohio. He continued his education at Cheyney (State) University, another Black university in Pennsylvania where he learned about peace activism and pacifism from the American Friends Service Committee. In the 1930s, he moved to live with a sister in Harlem and attend City College of New York. For the first time he was able to express his sexuality more fully, became active in the Young Communist League (YCL), the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) with A.J. Muste, and began a lifelong mentorship with A. Philip Randolph. His connection to communism, however, was short lived. Rustin’s pacifist beliefs and ongoing fight for civil rights didn’t fit within the Party, which called on members to cease all civil rights work during WWII. After he left the Party, Rustin would remain an anti-Communist for the rest of his life.

During 1941, Rustin worked to organize A. Philip Randolph’s proposed march on Washington to challenge the lack of employment opportunities for African Americans in the defense industry. (The march was called off after President Roosevelt issued Executive order 8802, which desegregated the defense industry.) Working with FOR, Rustin’s commitment to the non-violent direct action tactics used by Mahatma Gandhi deepened. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), established by James Farmer, was a component of FOR, and Rustin worked with CORE to apply Gandhian tactics to the cause of racial justice.

Rustin’s work with FOR, his pacifism, his Quaker faith, and the United States’ entry into WWII put him on a collision course with the draft. Rustin became a conscientious objector, and chose to go to prison rather than fight. He spent twenty-eight months behind bars where he led protests to advance integration and improved prison conditions.

In 1947, Rustin joined an integrated team of fourteen men who tested the Supreme Court decision, Morgan v. Virginia. The decision had outlawed segregation in interstate bus travel, but southern states were refusing to comply. This Journey of Reconciliation, which took place more than a decade before the more famous Freedom Riders of ’60 and ’61, traveled through the upper South. It ended violently and Rustin was arrested and sentenced to work on a chain gang in North Carolina, which he did for twenty-two days.

Randolph sent Rustin to Montgomery, Alabama in 1956 to investigate the bus boycott that was sparked by the arrest of civil rights activist Rosa Parks and organized under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., then a young minister. By this time, Rustin had participated in several direct actions and traveled to India for an international conference on non-violent direct action. Rustin convinced King to adopt the Gandhian principles that would become the cornerstone of the movement’s effectiveness.

Rustin mentored King on nonviolent direct actions and worked closely with him to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). But in 1960, in order to stop a protest planned by Rustin and the SCLC at the Democratic Convention, the African American congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. threatened to spread the lie that Rustin and King were having an affair. King’s acquiescence to Powell’s threat damaged the relationship between Rustin and King. Said Rustin, “Bigotry’s birthplace is the sinister back room of the mind where plots and schemes are hatched for the persecution and oppression of other human beings.”

As the civil rights movement leaders began planning the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, A. Philip Randolph insisted that a successful event would require Rustin’s organizing genius. Working tirelessly for eight weeks, Rustin brought approximately 250,000 people to Washington, D.C., and provided King the national platform for his famed “I Have a Dream” speech. A photograph of Randolph and Rustin, standing in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, graced the cover of Life magazine.

In 1964, following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Rustin wrote “From Protest to Politics” in Commentary magazine. He argued that the legal successes that came from the various protests throughout the South should be followed by deeper alignments with the Democratic Party and the labor movement, with the goal of linking civil rights to economic justice and entrenching the movement’s successes within established political institutions and processes. Additionally, he insisted that civil rights goals for African Americans would succeed only if they were included in a movement for economic justice for poor whites.

He used his position as the executive director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, established with a grant from the AFL-CIO, to advance his political cause. In order to do so, he had to compromise some of his core values and subsequently lost many friends. For instance, to support President Johnson’s civil rights initiatives in the middle 1960s, he did not protest the Vietnam War. Unlike Dr. King, Rustin thought he could separate racism and poverty from militarism and prioritize support for civil rights. Under criticism, Rustin said, “…I’m a pacifist to this extent: I believe that the first and most important thing we can do is to discover the means of defending freedom that men can use. It is ridiculous, in my view, to talk only about peace.”

Though he never hid his sexuality, Rustin did not participate in the LBGTQIA+ rights movement until later in life, and then, at the urging of his partner Walter Naegle. Rustin advocated for New York City’s gay rights bill, which was approved by the city council in 1986. Rustin linked the causes of African American civil rights and LBGTQIA+ rights, saying, “The barometer of people’s thinking [in the past] was the black community. Today, the barometer of where one is on human rights questions is no longer the black, it’s the gay community.”

Bayard Rustin died of a heart attack on August 24, 1987, and was survived by his partner, Walter Naegle. Though there had been attempts to erase and/or minimize Rustin’s role in the history of the civil rights movement, biographers like Jervis Anderson, Daniel Levine, and John D’Emilio, and projects like the documentary Brother Outsider, have ensured that Rustin’s legacy will not be lost. These projects document a remarkable man who was shaped by his deep integrity and courage, as well as his determination to advance the freedom of all people. In 2006, the newest high school in West Chester, Pennsylvania was named for Rustin, and in 2013, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. On March 8, 2016, Rustin’s New York City residence was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, one of the few listings that expressly recognizes LGBTQIA+ history.

Related News

Resources

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.