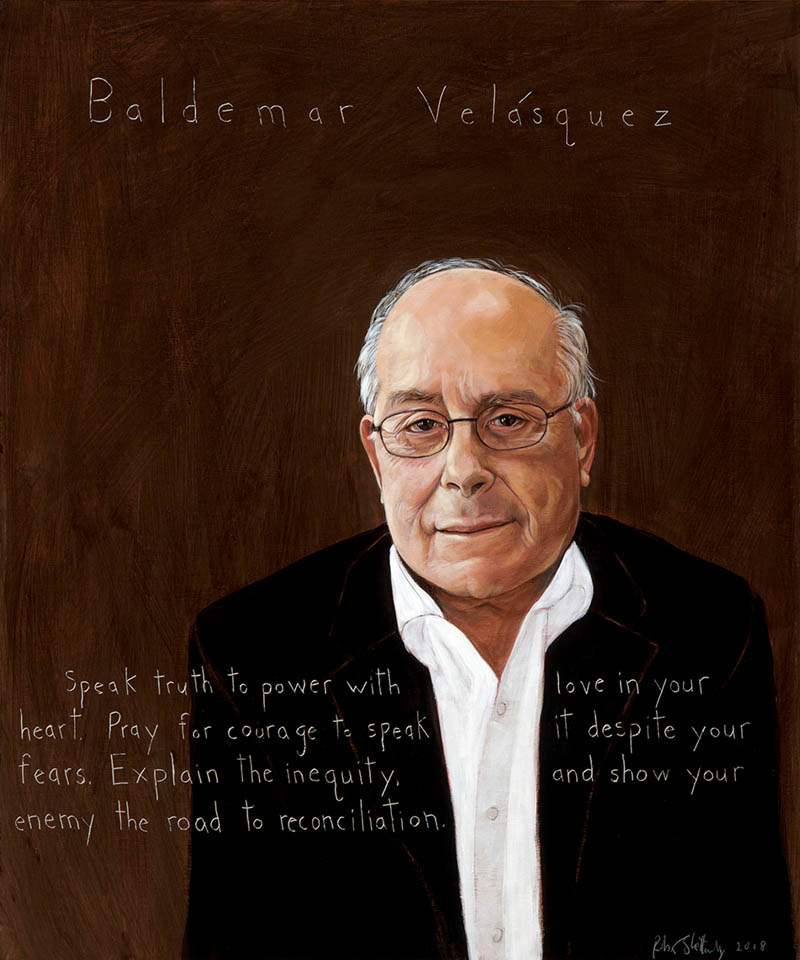

Baldemar Velasquez

Labor Organizer : b. 1947

“Speak truth to power with love in your heart. Pray for courage to speak it despite your fears. Explain the inequity and show your enemy the road to reconciliation.”

Biography

The first known labor organization in the United States was the National Labor Union (NLU), established in Baltimore, Maryland in 1866. The NLU sought to organize workers across various segments, including skilled and unskilled workers, as well as some farm laborers. The organization didn’t last, shuttering in the 1870s. When one reviews the history of the American Labor Movement, it’s noticeable that, except for a brief period during the 1930s and 1940s, agricultural workers of color rarely were included.

Historically, African American and Latino workers have been associated with the land, whether working on plantations in the American South or farms and ranches in the Midwest and Southwest. The American South was (and remains) notorious for its anti-organized labor sentiment, regardless of the workers’ race. This may be due to the feudalistic nature of the post-Civil War slave society and its rigid, cost saving control over laborers through sharecropping and peonage. As the South was an inhospitable climate for the Labor Movement, the first organization of farm laborers took place in the American West. The first successful farm laborer organization was the United Farm Workers, established by Cesar Chavez in California in 1962. Only five years later Baldemar Velasquez established the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) in Toledo, Ohio. Over time, Velasquez would expand his organizing effort to include migrant and seasonal farm workers.

Baldemar Velasquez was born February 15, 1947 in Pharr, Texas to Cresencio and Vicenta Velasquez. Both Cresencio and Vicenta were migrant farm workers who traveled from Texas to farms throughout the Midwest, planting and harvesting a variety of fruits and vegetables, including sugar beets and tomatoes. Velasquez was first introduced to the fields when he was four years old. He says, “me and my brothers and sisters were raised in labor camps, and we didn’t have any money to buy toys, so we played with the rats.” In an interview with the organization Food Tank, Velasquez recalled witnessing his “…family being cheated out of wages and suffer verbal abuses from field men, labor contractors, growers, and racist townspeople in the rural towns” where they worked.

After his family settled in Gilboa, Ohio in 1954, Velasquez continued as a seasonal farm worker through high school. After graduating in 1965, he became the first member of his family to go to college, matriculating at Pan American University in Edinburg, Texas. He would eventually graduate from Bluffton College (now University) in Bluffton, Ohio.

During his Bluffton years Velasquez volunteered with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights organization founded by Bayard Rustin. While volunteering with CORE, Velasquez told another Civil Rights activist the story about playing with rats as a child. The African-American activist asked Velasquez why he wasn’t working to help his own people. “That was the question of the decade,” said Velasquez, “and that summer after my sophomore year in [college], I started organizing the migrant workers.” In 1967, at the age of 20, Velasquez founded FLOC. He noted that “[w]e coined the phrase ‘the Farm Labor Organizing Committee’ after SNCC,” the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a Civil Rights Movement organization established by college students.

As FLOC got started, Velasquez “thought, mistakenly, that all we had to do was tell the regulatory people that these laws were being broken…you know, the child labor laws, the minimum wage laws…and they’d come in and fix everything, right?” Velasquez soon learned also that “[i]t was a big mistake to go after individual farmers.” Effective organizing required that he determine the true centers of power, so that protests could be directed at the interests of the proper parties, such as the corporations that purchased produce from farmers.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr invited Mr. Velasquez to Atlanta in 1968 to help plan the “Poor People’s Campaign” and he recalled something that Dr. King said that evening, “…when you impede the rich man’s ability to make money, anything is negotiable.” Velasquez translated this into his work in “every campaign that FLOC worked on…. trying to figure out…the financial leverage point of large corporations.”

In 1978, FLOC organized 2,000 of its members to strike against the Campbell Soup Company, seeking improved working conditions for farm laborers and recognition of the union itself. Eight years later, FLOC successfully negotiated a contract among workers, farmers and Campbell Soup. The contract provided recognition of FLOC as a union, increased the hourly wages of the workers, and provided some health benefits. The contractual arrangement was the first of its kind for farm workers. Three years later, Velasquez was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Fellowship. In 1994, Velasquez was the recipient of the Order of the Aztec Eagle, an honor given by Mexico to non-Mexican citizens who have contributed significantly to Mexican society. In the US, the National Council of La Raza recognized him with the Hispanic Heritage Leadership Award.

As the accolades came in, Velasquez continued organizing workers and his education; in 1991, Velasquez earned an advanced degree in Theology from the Florida International Seminary. In 1993 he was ordained by Rapha Ministries to chaplain the farm workers. Following the success of the Campbell Soup contract, Velasquez and FLOC negotiated similar deals with other major American food companies. Even with these victories, the 1980s and 1990s were particularly difficult times for the labor movement as a whole: “In this era of union busting, a call needs to be issued to organize for radical changes in the infrastructure of how the agricultural industry does its business,” he wrote.

Velasquez turned his attention to organizing migrant farm workers in the American South. Though it took several years, Velasquez and FLOC successfully negotiated a contract deal with the Mount Olive Pickle Company in North Carolina, the first joint contract among laborers, farmers and a corporation in that state. It was important for Velasquez to keep in mind when conducting these negotiations that “[d]irect employers are not entirely responsible for the many abuses, but consumers are smartening up to hold manufacturers and retailers also responsible for the consequential results surrounding food safety, the environment and worker rights.”

Currently, Velasquez is working to help undocumented immigrants. In an interview with the Toledo Blade, Velasquez called on FLOC members to adopt and support families with undocumented members: “[W]e need to act proactively and take care of our people.” And it is with that spirit that Velasquez reflects on his work, saying “as the victories come and the years go by, I will remember less the details of winning and losing and more acts of caring and love of the many people who have made FLOC possible.”

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.