What's New

Mary Oliver, a Grasshopper and Gaza

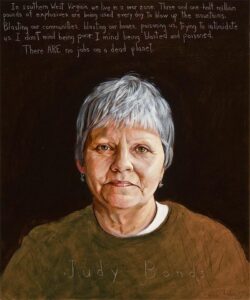

Early on in the Americans Who Tell the Truth project I traveled to West Virginia and eastern Kentucky to witness for myself what Mountaintop Removal (MTR) coal mining looked like. I wanted to see the devastation I’d been reading about and meet some of the courageous activists trying to stop it (Judy Bonds, Larry Gibson, Teri Blanton). The once beautiful Appalachian forest with over 500 mountains blown to smithereens was described as looking like a war zone.

That was true. And, today, the rubbled remains of Gaza are very similar to what those rubbled mountains look like – without, however, all the people fleeing for their lives. Or being buried in mass graves.

After returning from Appalachia, in the first schools I visited in New England, I asked the kids if they knew about MTR. They did not. We talked about the formation of the mountains – the oldest in the world – some 300 million years ago, the ecological wonders of their diverse flora and fauna, and the symbiotic relationship of mountain people and their culture to the indigenous plants and animals. We asked how the coal companies and the energy economy of this country could justify destroying the irreplaceable to increase their profit margin selling coal. Who has the right to blow up a mountain? You can’t grow back a mountain.

That early history of AWTT came back to me as I’ve been trying to write about the ruthless bombing of Palestinians in Gaza. I find it very hard to go on with my privileged, safe life while such horrors continue – especially because my country supplies many of the devastating weapons slaughtering two million civilians unable to defend themselves. So many thousands of children – like the ones I visit in schools here – blown to shreds. Just as the children are unable to defend themselves, I feel unable to do anything to stop it. Unable to defend myself from the burden of shame, guilt, anger and grief.

Thinking about those blasted mountains and the genocide of Gaza, I remembered Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day.” It’s a meditation on the meaning of our lives, the choices we can make, how being fully present to the miracles of creation can open our hearts and minds to being more deeply, and nonviolently, alive. It’s a poem adults read to each other, a poem teachers read to students, a poem ministers read to congregations, a poem a woman reads to the baby in her womb. It’s a poem we know can act as a portal of transformation – inviting us to travel through it and be awakened to wonder, be dumbstruck by the evolutionary, precious wonder of life.

When you read the opening line, “Who made the world?” Mary Oliver isn’t instructing you to answer, God. She’s asking you to examine a creature, or any created thing, closely – in this case the fantastic mechanisms of a grasshopper:

“This grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.”

One need not ask “who” made this. She’s really asking you to pay close attention and ask, How could this marvelous thing exist? And in the same world with me? She’s saying that there really may be no better use of your life than getting to know all your fellow travelers on this unlikely Earth. And then realize that you and everything else in the world are equally miraculous. There’s deep joy in that.

She ends the poem with two of the most famous lines of contemporary poetry:

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?”

I read the challenge of those lines and think of all the time I’ve squandered in distraction, or self indulgence, or consumption. So much time lost not being engrossed in the wonder and preciousness of life and loving, marveling. And then I think of those mountains being blown up – the millions of birds and mammals, oaks and sassafras, snakes and grasshoppers destroyed. But this is not about abstractions. Mary Oliver reminds us, “This grasshopper, I mean.” It’s about the evolutionary particularity of each individual. Who has the right to blow up a grasshopper?

And then I think bitterly of all the children of Gaza who will never be able to even attempt to answer the question about what to do with their wild and precious lives. To share those dreams with their parents. Other people have decided that these children are better off buried in rubble than asking anything about the future and hope. I think of survivors who will be consumed with trauma and rage, fear and revenge. Who knows if even a grasshopper survives in Gaza?

Who has the right to blow up a child?