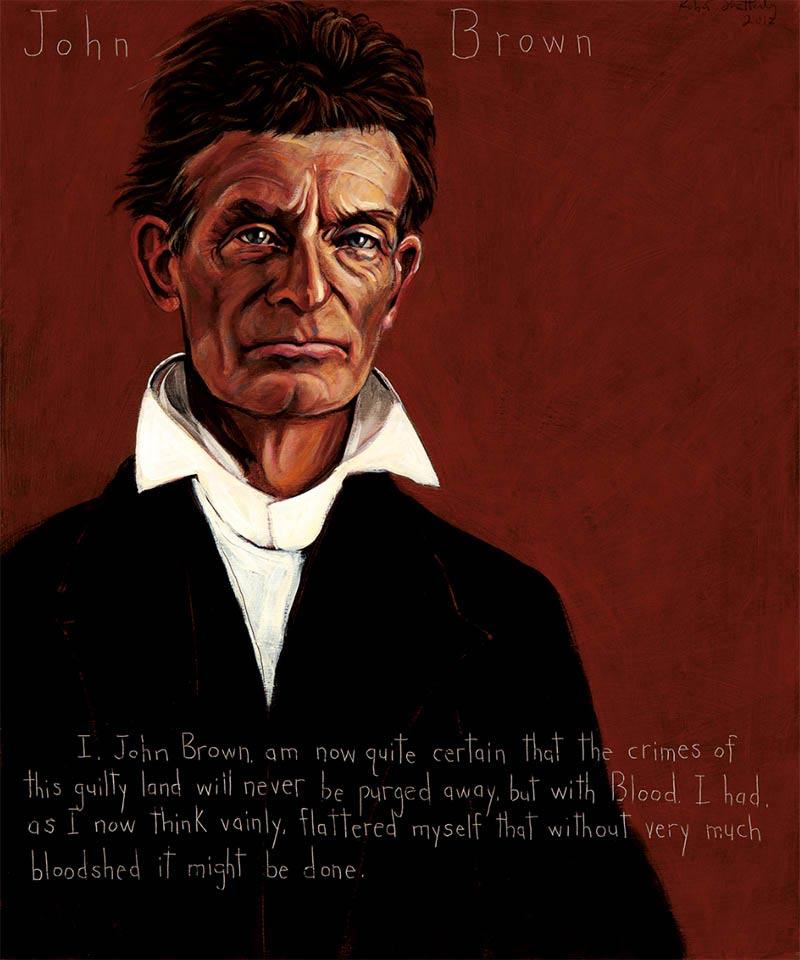

John Brown

Tanner, Sheep Farmer, Abolitionist, Martyr : 1800 - 1859

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had, as I now think vainly, flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

Biography

In July of 1859, with sectional tensions between the South and North near a breaking point—the Civil War would begin a year-and-a-half later—twenty-one men led by the militant abolitionist John Brown raided the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. They easily took control of the place (ironically, the only casualties were three African Americans, one free and two enslaved, accidently killed by Brown’s men). It was their plan to distribute the armory’s weapons to slaves throughout the region, who would then form a guerilla force sheltered by the Appalachian Mountains. From the cover of the mountains, the slaves would conduct raids against the South’s slaveholders, free and arm still more slaves, and quickly destroy the South’s “peculiar institution.” But instead of revolution, the U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee raided the armory, killed ten of Brown’s men, and captured seven more—including Brown.

This was not the first time Brown had resorted to violence. Back in 1855, Kansas was engulfed in a bloody struggle over whether the territory was to be admitted to the Union as a free or slave state. Brown moved to the territory and organized an informal paramilitary force intended to counter the bloodshed of the pro-slavery Border Ruffians. In 1856, amid increasing tensions, he and his men dragged five pro-slavery sympathizers from their homes in the middle of the night and hacked them to death with broad swords.

What are we to make of all this violence?

One way to understand Brown is to put him in the historical context of the early and mid-nineteenth century. Brown was born into a deeply religious Northern family during a time known as the Second Great Awakening, when a wildfire of Christian evangelism swept throughout the U.S. Especially in the North, a brand of Christian fundamentalism, known as postmillennialism, was flourishing. It held that the second coming of Christ would not occur until society lived in a perfectly Christian, moral, harmonious state.

This fundamentalist postmillennialism (so different from today’s ultra-Right Wing version) fueled progressive reform efforts, chief among them, abolitionism. Postmillennial Christianity instilled in many Northerners the urgent belief that the great sin of slavery was the biggest hurdle standing in the way of Christ’s reappearance, for Christ simply would not reveal himself to a nation of slaveholders. Though some abolitionists were actually quite racist, believing that slavery was a sin but that the U.S. was a white man’s country, a vocal and influential minority that included Brown condemned both slavery and racism in increasingly forceful terms. These were the abolitionists who undertook direct action, like helping to operate the underground railways. A few, like William Lloyd Garrison, actually burned the Constitution (because it protected slavery) and urged the North to secede from the South.

At the very same time, slavery was sinking its poisoned roots ever deeper into American politics and economics. Slavery was inherently brutal as slaveholders maintained their power over African Americans through what historians have described as state-sanctioned widespread torture: beatings, maimings, the dread of being sold away from one’s family, death. As the Civil War inched closer, it seemed that the power of slavery was only growing, and indeed spilling out of the South. The Compromise of 1850 included a strengthened Fugitive Slave Act, making it a crime to knowingly aid an escaped slave in any way; the Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 threatened to open the western territories to slavery; and the 1858 Supreme Court decision in Dredd Scott v. Sanford declared that no African American could ever be a U.S. citizen, and so had no access to the Federal justice system.

Yet, despite the context of religion-fueled radical abolitionism and extreme southern brutality, Brown’s actions stand out. Not only was he one of the most committed abolitionists of his time—three of his sons would be killed fighting for their father’s ideals—he was nearly alone in the equality and respect he showed African Americans, referring to them respectfully as “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” and even inviting them to share meals at the family table.

How, then, do we understand Brown’s actions in Kansas and Harper’s Ferry? Were they the work of a freedom fighter or a terrorist? Was Brown a patriotic American or a dangerous revolutionary? A martyr or a madman? Americans have been arguing about the morality of what he did for over one hundred and sixty years. Was Brown justified? The question is still unresolved because every answer quickly leads to a paradox at the heart of the American experiment: a government of laws founded by law-breakers, a people who pledge allegiance to the nation and yet whose everyday politics celebrates revolutionary violence.

Even the Declaration of Independence seems to sow the seeds of its own undoing: when any government will not protect its citizens, it is the peoples’ right “to throw off such Government.” “We hold these truths to be self evident,” runs the most famous line of the Declaration of Independence, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The role of government, the Declaration argues, is to protect these individual rights. On one hand, the Declaration is a philosophical statement of what constitutes a good government, whose interests it should serve, how it should run. But at the same time, the Declaration is also a declaration of war, a legal document that justifies breaking the law.

And so we’re back to the paradoxical question: In this nation of laws, when is unlawful violence justified? And what actions are justifiable when the nation’s laws themselves are immoral?

These questions continue to frame the internal debates of justice movements. There are those who argue that we ought to work within the system and those who argue that meaningful change can only come from the outside. The rift between Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, for instance, opened up such questions. Americans will probably never reach consensus as to John Brown’s legacy because there’s no one right answer to the Declaration’s paradox.

Yet, whatever one may think of Brown, there’s little doubt that his deeds did help to propel the United States into the Civil War, a war that ultimately resulted in the extinction of slavery in the U.S. And, though it’s common to see the Harper’s Ferry raid as a failure, in effect it achieved exactly what Brown wanted. Harper’s Ferry polarized the nation: the South saw it as confirmation of a Northern conspiracy to destroy their way of life. And it emboldened abolitionists in the North. Even Henry David Thoreau—whose eloquent cry for peaceful resistance, “Civil Disobedience,” would later inspire Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nonviolent methods—ultimately saw in Brown the only kind of determination that could kill slavery.

“He was a superior man,” Thoreau wrote:

No man in American has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature, knowing himself for a man, and the equal of any and all governments. In that sense he was the most American of us all.

Is an American someone who follows the laws absolutely? The South thought so. John Brown was convicted of murder, treason, and conspiracy, and was hanged on December 2, 1859.

Yet, as the war went on, many in the North believed that a true American would be uncompromising in the pursuit of the Declaration’s unalienable rights. In 1861, as Union soldiers marched south, they sang a new, vengeful battle song whose first verse ended with: “John Brown’s body lies a’mouldering in the grave/ His soul is marching on.”

__________________________________________________

Source:

Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown,” in Walden and Other Writings (New York: The Modern Library, 1937) 695.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.